April 26, 2023

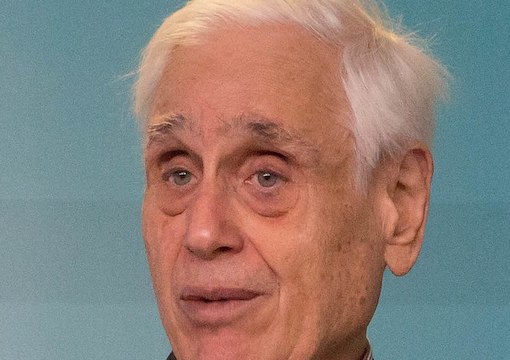

Edward Jay Epstein

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Ever since his 1966 book Inquest documented that the Warren Commission’s own staffers believed that their enquiry into who shot JFK had been too rushed to be reliable, Edward Jay Epstein has been that highly useful rarity: a center-right heavyweight investigative journalist.

Epstein’s new memoir, Assume Nothing: Encounters With Assassins, Spies, Presidents, and Would-Be Masters of the Universe, recounts his Zelig-like career as a confidant of the rich and powerful around the world (even while often going on to reveal their embarrassing secrets).

Epstein, now in his mid-80s, was a star during the legendary Tom Wolfe Era of magazine journalism when nonfiction writers could become moderately wealthy writing for the big New York magazines. In that long-gone era, reporters were expected to subvert power, not be the ill-paid but loyal servants of the system as they are today.

And yet, Epstein’s career flourished because the mighty tended to see him as a potential sympathizer and thus often provided him with abundant human interest material about themselves before he stuck the shiv in.

For example, after Epstein had heard a former chief financial officer of Occidental Petroleum describe his ex-boss Armand Hammer as “the Nijinsky of bribery,” he got himself commissioned by The New York Times Magazine to write a profile on the celebrated oil tycoon. Back then, Hammer was a candidate for the Nobel Peace Prize due to that communist capitalist’s friendships with both Kremlin premiers and Republican presidents.

Rather than tell the nosy reporter to go jump in a lake, Hammer set out to win over Epstein, inviting him and his girlfriend to a dinner at which the three other guests were the owner of the Times, the First Lady, and the Prince of Wales. For months, Hammer took Epstein on his travels, introducing him to Bob Hope, Saudi ambassador Prince Bandar, Al Gore, and Pierre Trudeau.

But Epstein’s friend James Jesus Angleton, who had been deposed as head of CIA counterintelligence after he perhaps got lost in espionage’s “wilderness of mirrors,” warned him there was “another side” to Hammer and suggested Epstein get ahold of secret Soviet documents seized by British intelligence in 1927.

But how? Fortunately, Epstein’s research assistant was the daughter of a former British cabinet minister and a best-selling historian who had remarried Nobel laureate playwright Harold Pinter (who, Epstein recounts, cheated at bridge). The British spy archives showed that the Bolshevik billionaire had been Lenin’s and Stalin’s American fence for stolen art treasures.

Eventually, Epstein got his hands on sixty hours of Nixon Oval Office-style tapes that Hammer had made of himself bribing government officials, which vindicated the credibility of his 1996 exposé on Hammer, Dossier.

On a lower level of scandal, Stephen Ross, a mortician who somehow became one of the most powerful men in American media as owner of Time-Warner (and whom Epstein recruited to fund his mentor Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s 1976 Senate campaign), is depicted cheating at Scrabble. The night before playing with Epstein and socialite Amanda Burden, the mogul had carefully pocketed the tiles that spelled the high-scoring word “zygoma.” The next day, he used sleight of hand to lay them down and declare himself the winner.

The South African Oppenheimers, the central figures in Epstein’s terrific book on the De Beers monopoly, Have You Ever Tried to Sell a Diamond? (which Epstein makes available for free on his website), don’t wind up looking as bad as Hammer. On the other hand, after reading Epstein on the diamond racket, you’ll never watch an engagement ring TV commercial the same way again.

Not every rich and powerful man who tried to impress Epstein paid as big of a reputational price as the odious Hammer did. For instance, Sir James Goldsmith, whom Epstein met at a dinner party at Taki’s, comes off fairly well in Assume Nothing.

So does Richard Nixon, whom Epstein met at Goldsmith’s Mexican rancho. To Epstein’s surprise, the elderly Nixon proved an ideal leader of serious conversation at the dinner table, sensitively giving each guest a chance to shine about what he knew best, like a hobbling but wily old quarterback finding ways to get the ball to the athletes in the open field.

The academics whom Epstein taught with at Harvard and MIT before becoming a full-time journalist—social scientists Moynihan, James Q. Wilson, Edward Banfield, and Andrew Hacker, along with mathematician Tom Lehrer, the legendary songwriter and, according to Epstein, inventor of the Jello-O—also appear in a good light.

From his Ph.D. adviser Wilson, author of the political science classic Bureaucracy, Epstein learned the “organizational theory” perspective that made him averse to assuming that all the scandalous disclosures he uncovered necessarily added up to some overarching conspiracy. While there are some real-life Bond villains like Hammer, most things get done by large organizations of officials of highly constrained competence. (Even the top guys don’t know that much: The funniest example of this is that on his way out of the White House, Barack Obama connived to get his daughter an internship with…Harvey Weinstein.)

For instance, even though Epstein’s JFK book Inquest was essential to the growth of American conspiracy theorizing by proving just how fallible the Warren Commission had been, Epstein himself, over three books on the assassination, never adopted a particular conspiracy theory. To Epstein, the time limitations put on the investigating staffers by Chief Justice Earl Warren—such as that they couldn’t go to Dallas until after Jack Ruby’s trial was finished, and then they had to wrap up before the election—did not appear to grow out of some nefarious plot to cover up the awful truth. Instead, they simply appear to have turned out to have been mistakes that had seemed like good ideas at the time to Warren.

It’s not immediately obvious why so many cunning men didn’t flatly turn down this dangerous journalist’s entreaties. Epstein himself sketches an explanation on the first page of his memoir. For one thing, he’d grown up in New York affluent and Jewish at a time of rapidly growing Jewish success. (Numerous rich Jews seemed to assume that he’d pass up exposing their foibles because that wouldn’t be “good for the Jews,” but Epstein isn’t very ethnically biased.)

But his big advantage, he writes, was that at age 12, a difficult time for most boys, he was already 6′ 2″ and 200 pounds. This precocious size “conferred on me a bold social confidence that would remain.” Whereas magnates tend to see most reporters as ink-stained wretches, many seemed to find the audaciously assured Epstein as, by nature, a fellow buccaneer.

Hence, Epstein’s book includes a remarkable array of encounters with the rich, famous, and notorious, from Vladimir Nabokov to Jeffrey Epstein.

As a sophomore at Cornell, he signed up for Nabokov’s legendary course on European literature. But he hadn’t gotten around to reading any of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, so he was initially stumped by his professor’s single essay question: “Describe the train station in which Anna first met Vronsky.” But he had seen a movie adaptation starring Vivien Leigh, so he filled up the test booklet with every detail from the movie. When he finally read the novel, however, he discovered that the director had made up much that wasn’t in the book.

Hence, when Epstein got a note to meet with Professor N., he figured he was being flunked out. But it turned out that Vladimir and his wife-assistant Vera, not having seen the movie, had assumed that they had discovered a creative prodigy. They even offered Epstein the undergrad English major’s all-time dream job: to see all four movies playing in Ithaca each week and advise the Nabokovs on which one they should watch on the weekend.

The work went well for a couple of months until Epstein reported back on a movie based on a Pushkin short story.

[Nabokov] seemed uninterested in having me recount the plot, which he must have known well, but his head shot up when I said in conclusion that it reminded me of [Gogol’s] ‘Dead Souls.’ Vera also turned around and stared directly at me. Peering intently at me, Nabokov asked, “Why do you think that?” I instantly realized my remark apparently connected with a view he had, or was developing, concerning these two Russian writers. At that point, I should have left the office, making some excuse about needing to give the question more thought. Instead, I said pathetically, “They are both Russian.”

His face dropped…

While researching the Vatican Bank scandal in 1988, Edward Jay Epstein met Jeffrey Epstein through Goldsmith (who didn’t seem impressed with the second Epstein).

This younger Epstein was an amiable con man from the beginning. He offered to upgrade the older Epstein’s airline ticket to first class for free. But the third time the elder Epstein tried to use the younger one’s upgrade service, he was ignominiously booted out by the ticket clerk:

When I pointed to the first-class sticker, she said anyone could steal one and paste it in. I was unceremoniously moved to coach.

A friend says that the media business is about two things: public relations (of which the subdivisions are hype and damage control) and accounting (finding the money and hiding the money). The author’s conclusion, based on what Jeffrey Epstein told him in the 1980s, is that his financial specialty was hiding the money from the taxman, and names Leslie Wexner and Leon Black as likely billionaire clients.

Not surprisingly, Jeffrey Epstein wanted to hear from Edward Jay Epstein all about his old professor, the author of Lolita. The jailbait aficionado was disappointed that the author’s recollections of that great man of letters were so seemly.