May 01, 2014

Source: Shutterstock

Last Tuesday, the U.S. Supreme Court decided by a 6-2 margin that the 2006 Michigan voter-initiated ban on racial preferences in college admission was constitutional.

Superficially, the Schuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action ruling seemed a momentous if not explosive decision. The five conservative justices wrote three different opinions (Stephen Breyer, who usually votes liberal, supplied the sixth vote), while Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor read an emotional 58-page dissenting opinion in open court.

In reality, the decision merely affirmed the right of Michigan voters to pass referenda. Writing for the majority, Justice Kennedy tried to defuse hyperbole by stressing what the decision was not meant to decide: “This case is not about the constitutionally, or the merits, of race-conscious admissions policies in higher education.” The decision left untouched the race-based admission policies in 42 other states.

Even in Michigan, the end of affirmative action will hardly deny any capable black student access to higher education. In the long run Schuette may benefit minority students. A high school senior who just missed the cut at the state’s flagship university would surely be welcomed at schools a notch below, where he could flourish in a setting appropriate to his abilities instead of being shunted into a basket-weaving major. And for a student who does make the cut, his degree will not be cheapened.

But affirmative action aficionados panicked anyway. Eugene Robinson, writing in the Washington Post, claims that Michigan’s 2006 constitutional amendment “unfairly burdens racial minorities,” as if an electoral defeat ipso facto constitutes an unfair outcome. Justice Sotomayor offers a similarly twisted view of democracy (celebrated in a New York Times editorial) when she asserts that our Constitution prevents the majority from oppressing minorities, and that Michigan voters were oppressing blacks by forbidding racial preferences. She added that the majority failed to acknowledge the impact of “centuries of racial discrimination,” as if this impact were a well-documented scientific law. Not to be outdone in the indignation Olympics, Al Sharpton announced that the decision is “a devastating blow to the civil rights community.”

Why the gross overreaction? Jobs. Admitting hordes of underqualified students to top schools is an employment bonanza for middle-class blacks. It is said that every combat soldier requires seven in support, and this ratio probably applies to pushing academically “challenged” minority students through school.

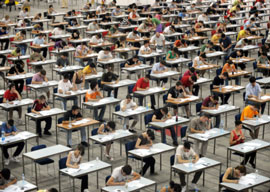

Bureaucratic expansion begins in the admissions office. Since explicit racial discrimination risks litigation, admissions counselors must be hired to scrutinize minority applications to uncover special talents that trump test scores and high school grades and thus justify blatant racial discrimination. As the students arrive on campus, they may need summer bridge programs, where counselors will teach them the basics of college life. Their need for housing and varied recreational activities will mean hiring more culturally competent staff. When classes begin, yet more tutoring and advising functionaries will step in and work their magic. Then the newly minted scholars will need an entire identity-based department catering to their academic interests, from tenured professors, to secretaries, to undergraduate advisors.