October 02, 2011

Why did this popular passion for “great books” eventually dwindle? I believe it did not suit most educators, who were narrowly specialized or fixated on political agendas. Why should a professor who knows zilch about the humanities have to teach something he never studied? During my graduate-school years at Yale in the mid-1960s, foreign-language students were more into Marxist or postmodernist theories than the received national literatures they were supposed to be absorbing. If you read the Hungarian communist Georg Lukács, it advanced your career more than reading Goethe, Racine, or Cervantes. An English professor of deep Southern origin once explained to me that while teaching Shakespeare, it dawned on him that we learn more about social justice via Maya Angelou than Elizabethan texts. Core curricula at most colleges no longer provide any serious exposure to the humanities. To the extent that modern instructors present anything other than writing mechanics, it is typically about popular entertainment or designated victim groups’ suffering.

At least one university (Chicago) and several colleges—St. John’s in Annapolis, St. John’s in Santa Fe, and Thomas Aquinas College in California—have continued teaching the classics at the undergraduate level. But most of these programs are run by those providing a specifically Straussian reading of the assigned texts.

By the 1960s Straussians established themselves at many institutions as the authorized teachers of great political works. Strauss and his disciples claimed to be able to find “secret meanings” in classical texts, allegedly ascertained by reading dead white males through the proper filter. Most of the authors they taught were, like the Straussians, religious skeptics. Although one should not dismiss everything that Strauss wrote, he bequeathed to his students—and to their students—a cultish way of approaching texts.

By a process of elimination, those who stay in the field think and teach like their predecessors. The Straussians are far from alone in driving away prospective humanities students. They may in fact be among the least offensive ideologues in a field that has been overrun by them. Other approaches may be even more deadly—for example, listening to a feminist or homosexual professor furnish a “sensitive” reading of a particular text. This may have been a turnoff for many who might otherwise have grooved on such works. Students with differing perspectives, or so I’ve been told, look elsewhere for things to study when they encounter the “usual Straussian grid.”

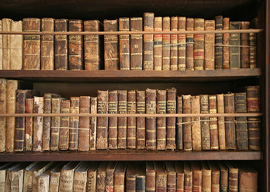

After WWII it seemed chic to at least appear to know something about the humanities, and people decorated their homes with bound volumes of the classics the way college students now paste rappers’ pictures onto their dormitory walls. During my adolescent years, we made fun of all the “culture vultures.” But for all their posturing and tasteless decor, these nouveaux riches look admirable in retrospect.