October 02, 2011

My friend Daniel J. Flynn is publishing a book called Blue Collar Intellectuals. One chapter I’ve seen in proofs, “The People’s Professor,” got me to thinking about a development in post-WWII America it is hard to imagine taking place in the present age.

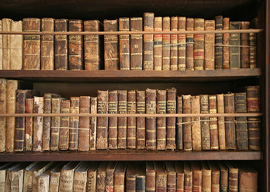

After the war, large numbers of Americans suddenly began to order the classics—ancient and medieval as well as modern—for their bookshelves. At some level, postwar Americans valued what they understood to be the funded wisdom of the ages. Still, an estimated fifth or more of the buyers of “classics collections” never opened the volumes and simply attached importance to having them around. Publisher and book critic Clifton Fadiman joked about people flaunting new editions of such ancient scientists as Apollonius, Nicomachus, and Ptolemy.

To capitalize on this trend, Robert Hutchins, Mortimer Adler, and William Benton—an ad tycoon who was a one-term Democratic Senator from Connecticut—launched an elaborate for-profit project to awaken enthusiasm for the “great books.” Adler, with some assistance from Benton, who was then also producing the Encyclopaedia Britannica, managed by 1952 to put together and market the Great Books of the Western World series. At the same time Adler and Hutchins integrated their business venture into the undergraduate curriculum at Chicago, and professors such as Leo Strauss were brought there to teach the featured works. Adler modeled this approach to learning on the Great Books Program—pioneered by such renowned educators as John Erskine and Mark Van Doren—that Columbia had introduced decades earlier.

As a businessman Adler had to deal with an earlier “great works” collection against which his project would be competing—the Harvard Classics that had been assigned to Harvard students for decades. But Adler marketed his collection better. It was longer than the Harvard Classics, came with abridged versions of the windier texts, and it looked great on socially ascending Americans’ shelves. Adler put his collection of old works into the homes of hundreds of thousands of consumers, marketing it shamelessly though any print or electronic medium then available. And everywhere he played up the snob value of owning and displaying the Great Books.

Leo Strauss and his followers must be understood in the context of this craze for the classics. Strauss and the Straussians did not create the trend but with Adler, they rode it to success. The trend may have been driven by postwar America’s longing for cultural continuity. At that time Americans saw themselves standing athwart two forms of totalitarianism—Nazism and communism—while representing some kind of “Western heritage.” For them, “the West” did not come down to a pluralist experiment or some boilerplate about human rights. Interest in “great books,” and even the ones that were unread, overlapped other trends such as revived interest in natural-law theory (which Adler, who became an Anglo-Catholic, promoted) and an obsession with the dangers of “relativism.”