May 23, 2017

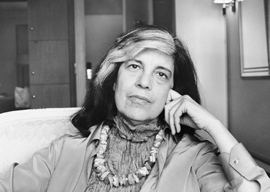

Susan Sontag

I still haven”t memorized my cell phone number, or my husband’s. I don”t remember the year my mother or father died, let alone the month and day. I can”t remember my wedding anniversary, either.

However, I”ve never forgotten that, sometime between the release of Annie Hall (1977) and Manhattan (1979), Woody Allen was the subject of a cover story in either Newsweek or Time in which”while musing bitterly about random, pointless suffering”he put in that cultural critic Susan Sontag’s cancer diagnosis “must have been particularly devastating for a woman of her sensibility.”

I”d never heard of Sontag or even “sensibility” before, but my teenage brain instantaneously turned up, like a tarot card, the image of a slender, serene patrician woman in a book-lined study, a secular Lady of Sorrows, her carefully cultivated cerebral life cruelly mugged by a base bodily affliction (in much the same way, I thought next, as mine was by my mother’s calls of “Dinner!” or “Dishes!” or some other”sigh!“quotidian triviality…).

I vowed to learn more about this Sontag lady, as part of my ongoing preparation (inspired, as it happens, by Woody Allen) to decamp Hicksville for a real city, packed with (other) witty, artistic, important personages, and fulfill my destiny as”at last I had a word for it!”a woman of a certain “sensibility.”

I duly discovered a dusty paperback of Against Interpretation at the used-book store, and studied Sontag’s author photo: an impossibly lovely if slightly severe brunette, her eyes averted, her giant brain obviously uncontaminated by tedious female nonsense like what Kleenex ply to buy, or what to put in the meat loaf.

And I got no further. I simply wasn”t bright enough to discover that precious Woody-approved “sensibility” presumably woven through Sontag’s daunting prose.

However, Deborah Nelson has, belatedly, helped me out.

Her new book, Tough Enough, considers what reviewer Katie Fitzpatrick calls “heartlessness as an intellectual style,” especially as adopted and deployed”as it so rarely is”by women, six in particular, including Sontag.

Fitzpatrick explains:

Nelson examines a group of thinkers (Diane Arbus, Hannah Arendt, Joan Didion, Mary McCarthy, Susan Sontag, and Simone Weil) who cultivated a cool, unsentimental disposition. Unsurprisingly, this attitude frequently inspired the disdain of their male colleagues, who saw them as “pitiless,” “icy,” “clinical,” “cold,” and “impersonal.” Several of these women also became notorious among the broader public for adopting an unsentimental tone at exactly the moments when sentiment seemed most necessary. Arendt criticized what she saw as the overly emotional language of the Israeli prosecutors at the trial of Adolf Eichmann; Didion satirized the smug good intentions of the New Left; Sontag, less than two weeks after 9/11, chastised U.S. officials and the media for their “sanctimonious, reality-concealing rhetoric.”

How could I (a.k.a. “Ming the Merciless“) not order this book before even getting to the end of that review? Simone Weil had been an exasperating yet inspirational “familiar” to me in my 20s. Every crazy, artsy girl loves Diane Arbus” off-kilter photographs of freaks. I”ve developed a late-in-life appreciation for Didion, having always assumed she was just another bicoastal, big-name liberal bore.

Finally, I”d crack the indelible pubescent puzzle of Sontag’s rarefied “sensibility””and wouldn”t you know it, the words “Susan Sontag” and “sensibility” appear on page four.

Indeed, there is much to savor throughout:

For instance, the posthumously published essays of saintly weirdo Weil, which promote a stringent “unsentimental compassion,” confounded certain 1950s American tastemakers.

“That such an ugly woman should be so compelling seemed preposterous, to say the least,” Nelson relates. “Moreover, that this unattractive and physically fragile woman should have expressed herself with such tremendous authority seems to have produced some confusion and irritation.”

Meanwhile, Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963) is greeted with considerable confusion and even condemnation, due in large part to its insufficiently reverent “tone.” Jewish scholar Gershom Scholem joins this chorus, scolding longtime friend Arendt for her “heartless” prose. Nelson notes astutely:

His insistence on heart, however, can be seen as a protocol-in-the-making for the treatment of the Holocaust…

And Arendt responds to Scholem:

“I do not “love” the Jews, nor do I “believe” in them; I merely belong to them as a matter of course, beyond dispute or argument…. We both know, in other words, how often these emotions are used in order to conceal factual truth.”

A professed loyalty to truth (or “the facts” or “reality,” depending on which of the Tough Enough women is under discussion)”and not “feelings” or “community” or “ideology””is the traditionally masculine trait they all share.