February 02, 2022

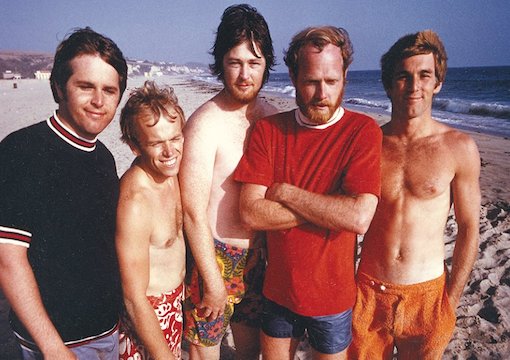

The Beach Boys

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Did the famous decade of pop music that followed the Beatles’ 1964 British Invasion spread leftist ideas? Many think so. For example, economist Tyler Cowen writes:

People tuned into the radio, in part, for ideas, not just tunes. But the ideas that spread best were attached to songs. Drug use spread, in part, because famous musicians sang about using drugs. Anti-Vietnam War themes spread through songs, as did many other social movements.

But did leftist lyrics inculcate leftist ideas? If so, it ought to be easy to name scores of well-known politically relevant songs from this immensely famous era of pop music.

A striking paradox is that only a tiny number of the best-known lyrics of the era were overtly political, with some even being on the right. For instance, Lynyrd Skynyrd topped Neil Young’s whiny “Southern Man” with “Sweet Home Alabama.”

The Beatles’ two most famous politically explicit songs are “Taxman,” in which George complains about high taxes, and “Revolution,” in which John disses Maoism and mostly peaceful protests.

This is not to say that Lennon and McCartney were apolitical. One revelation of Peter Jackson’s eight-hour Get Back documentary about the 1969 recording of the Let It Be album is that John and Paul avidly followed politics in the newspapers in a slightly middle-aged fashion.

But in his songs during his pre-Yoko prime, the contrarian John tended to wax anti-politics and pro-drugs:

You say you’ll change the constitution

Well, you know

We’d all love to change your head

You tell me it’s the institution

Well, you know

You better free your mind instead

But if you go carrying pictures of Chairman Mao

You ain’t going to make it with anyone anyhow

Strikingly, Paul was the more serious-minded liberal thinker of the pair. As early as 1965, he sat down for two lengthy sessions with the ancient philosopher Bertrand Russell to learn why Russell opposed the Vietnam War, and came to agree with him. (By the way, McCartney has the shortest known living handshake link to Napoleon: Paul shook Earl Russell’s hand, who was raised by his prime minister grandfather who had interviewed Bonaparte on Elba in 1814.)

For example, Paul demoed a song during the Let It Be sessions called “Commonwealth” scoffing at Enoch Powell’s opposition to immigration from the now-almost-forgotten British Commonwealth of former imperial possessions.

But the Beatles didn’t go ahead with it. They mostly avoided releasing topical political songs, just as George’s friend Eric Clapton didn’t write his anti-immigration views into “Layla.”

Or consider Bob Dylan. As an adolescent, he wanted to be a rock & roller in a leather jacket. But then Elvis got drafted and the craze died down. So Dylan hitched on to the latest fad: folk music.

Folk music had been around forever, and since at least the 1930s had been a genuinely leftist collectivist genre with roots in communist-affiliated unions and summer camps. Dylan quickly mastered the form, but a style of music intended for the masses to sing along with chafed at his individual genius and ambition to be an Elvis-like star. When the Beatles landed in 1964, Dylan quickly realized that rock was back and he could dump folk.

His “Blowin’ in the Wind” from 1962 is a nice civil rights song. But subsequent peak Dylan, with his extravagant imagination and gift for language, is hard to parse politically, probably intentionally.

His 1964 “My Back Pages” appears to be Dylan turning his back on his youthful leftist political certainties:

“Equality,” I spoke the word

As if a wedding vow

Ah, but I was so much older then

I’m younger than that now

But did “My Back Pages” reflect Dylan’s intellectual evolution to a more conservative ideology? Or was it more a signal of his career intent: that he was justifying his coming betrayal of his folk fans when he would pick up the electric guitar and play it loud?

What exactly Dylan’s politics have been since the mid-1960s remains obscure. (They are probably nothing very exciting.)

How about Motown? Rolling Stone magazine is always playing up Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On?” for being a lovely song with liberal lyrical content. On the other hand, the Temptations’ “Ball of Confusion,” written by the great Motown staffers Barrett Strong and Norman Whitfield, is comparably strong hotep reactionary songwriting:

Evolution, revolution, gun control, sound of soul

Shooting rockets to the moon, kids growing up too soon

Politicians say more taxes will solve everything

Creedence Clearwater’s 1969 tune “Fortunate Son” is a roaring two minutes of working-class leftist populism angry over draft deferments for college boys. It has become deservedly famous from its use in documentaries about the Vietnam era, but that’s partly because there aren’t many other hits from that sociological perspective for documentarians to choose from.

Antiwar rock songs were not uncommon during the later Vietnam years when the Nixon administration was winding down the war, such as Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s “Ohio” and their cover of Joni Mitchell’s “Woodstock” in 1970. But earlier tracks assumed to be Vietnam protests often weren’t, such as Buffalo Springfield’s eerie 1966 single “For What It’s Worth,” which was actually about anti-curfew riots by teens swarming the Sunset Strip.

What about social movements such as feminism and gay lib? There was Helen Reddy’s slightly lame 1972 hit “I Am Woman,” and then there was… Well, I’m drawing a blank on further feminist classics from that era. Aretha Franklin’s version of Otis Redding’s “Respect” is lauded as feminist, but it’s a black woman complaining about her stereotypically freeloading yet sexy black man.

Similarly, this was a bad decade for gay musical tastes. The rise of the lyrics-drowning electric guitar erased the coolness of Broadway show tunes. It wasn’t until disco emerged in the later 1970s that gay songs like “YMCA” and “In the Navy” could thrive.

There is one electric-guitar rock classic that’s obviously intended to be a gay anthem: “All the Young Dudes,” which David Bowie composed for Mott the Hoople in 1972. On the other hand, from looking at lists of songs that actual gays think of as their own, I don’t see much enthusiasm for it. (My impression is that Bowie was never terribly gay, but that he mostly pretended to be to divert attention from his real passion: black girls.)

You can tell how hard it is to dredge up overt examples of leftist songs by the exertions boomer music mag Rolling Stone went through when revising their Top 500 Songs list for 2021. For forgivable branding reasons, in their previous ranking in 2004, Rolling Stone’s No. 2 all-time track was “Satisfaction” by the (surprise) Rolling Stones, and No. 1 was, of course, Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone.”

But during the racial reckoning, the old white guys have been demoted. Now the top slot is given, for reasons of intersectionality, to “Respect,” despite that track’s mediocre sound quality compared with what Motown, much less George Martin, was achieving in 1967. (Aretha sounds like she’s standing eight feet from the microphone.)

For racial-reckoning reasons, No. 2 is Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power,” which Rolling Stone subscribers would know from Spike Lee’s 1989 Do the Right Thing movie.

And third is the usually tuneful Sam Cooke’s forgettable “A Change Is Gonna Come,” his uninspired response to “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

This isn’t to say that late-1960s music didn’t have a huge impact on cultural politics. It did, but less through lyrics than through sight and sound.

Drug use was encouraged by the extraordinary new noises that drugged musicians were coming up with.

The immense controversy over men’s hair length, starting from the Beatles appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, seems baffling to younger people today. But it served as a proxy for fundamental disagreements over social organization.

The near-universal short hair of the post-1945 era symbolized support for the triumphant military values that had won the Big One and were protecting the free world from communism, while long hair (which before the Beatles was respectable only when worn by classical musicians) suggested you were more individualistic, artistic, and self-centered.

The postwar ideal had been that the way a man won a woman was by first proving himself to other men. This was seen as making for a stable society in which institutions like the draft were accepted.

But the Beatles were a reminder that you could get girls not just by being a man looked up to by other men, but also by appealing directly to girls themselves, such as by having attractive long hair. That the Beatles could reject crew-cut masculinity but still pull even more girls than Mickey Mantle was profoundly discombobulating in 1964.

In summary, if you ask me to sum up in a single word what the lyrics of 1964–1973 were most about, I’d say: girls.

For example, one of the key driving forces of the decade was the artistic rivalry between the Beatles and the Beach Boys, especially after they both started taking LSD. And what was the first song Brian Wilson wrote on acid? “California Girls.”

But asked to epitomize the sound of that decade dominated by the electric guitar, I’d respond: masculine self-assertion. For instance, did the Who intend “Won’t Get Fooled Again” as a leftist or a rightist parable? I don’t know. It works either way.

But what I do know is that it’s four young men making a mighty noise, which, by 2022’s standards, deems it, and most of the best songs of its era, unforgivably transgressive.