July 16, 2009

Germany’s future lies to its Right.

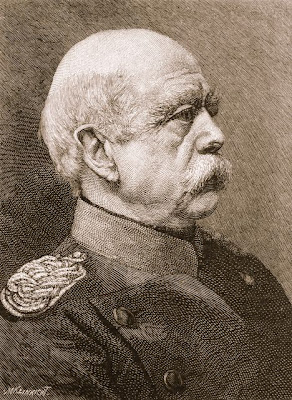

Otto von Bismarck, Germany’s prince of diplomacy, once remarked, “With France we shall never have peace; with Russia never the necessity for war, unless Liberal stupidities or dynastic blunders falsify the situation.” While all is thankfully quiet on the Western front, Berlin is taking a page from the Iron Chancellor’s playbook and forging strategic links with Moscow.

Energy has proven essential between Germany and Russia, since Moscow supplies the German economy with over 40 percent of its natural gas. And to ensure that German end-users will not be affected by Russia’s various disputes with transit nations, the Kremlin is building a new pipeline. The Nord Stream project, set to run through the Baltic Sea and slated to come online in 2010-2011, would cement ties between Moscow and Berlin and bypass countries like Ukraine and Poland. The Germans, whose companies have a significant stake in the venture, prefer to sidestep East European issues entirely and maintain a secure link to Russia’s resource base.

While energy is a key dimension of the Russo-German relationship, it’s not the only one. In June Moscow’s Sberbank acquired 35 percent of the automaker Opel in a deal orchestrated at the top levels of power. Opel has been racked by financial woes brought on by the economic crisis, which were only compounded since its parent company had been the now-bankrupt GM. German Chancellor Angela Merkel considered GM responsible for the mess and was angered by Washington’s refusal to take part in the clean up. Berlin was happy to accept Russian funding for Opel, while the Russians have gained access to advanced manufacturing technologies they can put to use for domestic production.

What German diplomats call Verflechtung, or strategic interlocking, with Russia has been driven by joint interests. Partnership with Moscow has also coincided with a downturn in relations with Washington. It’s no secret that Angela Merkel and Barack Obama don”t get along well, but the matter extends beyond poor personal chemistry to divergent national priorities.

A major point of disagreement between the two capitals has been how to grapple with the world financial crisis. As the U.S. amasses trillions in debt through stimulus spending- and paves the way for hyperinflation”Obama is encouraging Western partners to follow suit. But the Germans aren”t taking the bait. Merkel and her colleagues share a collective memory of the ruin that postwar debts and fiat currency brought to the Weimar Republic. Answering Obama’s request for substantive European assistance in Afghanistan, Berlin pledged just a few hundred additional troops to its force there. Germany’s reluctance to become further involved in the Afghan counterinsurgency speaks volumes about its lack of confidence in NATO efforts to stabilize the Hindu Kush, as well as the general direction of U.S. “global leadership”.

Since the collapse of Soviet power, it’s been all but inevitable that Germany would begin to chart a course separate from that of the United States. Berlin’s objections to the U.S. invasion of Iraq were only the first major manifestation of discord between NATO allies. The Bundeskanzlerin has effectively put the brakes on Washington’s expansion of the North Atlantic alliance into the Caucasus and Ukraine. In light of Russian resurgence heralded by the 2008 war in Georgia, the Germans consider further U.S. encroachment in the former Soviet Union an unwise and dangerous proposition.

Germany is looking after its own interests regarding Russia, and it’s much more interested in partnership than confrontation in Eastern Europe. Though German citizens retain some anxiety about Russian revisionism, they also attribute this phenomenon to U.S. interference on Moscow’s periphery. As long as the White House continues to view NATO expansion into the former Soviet space as a long-term objective, its designs will run up against Germany’s refusal to be involved in another showdown with the Kremlin. Any likely deployments Washington plans for Poland or the Czech Republic will receive little German support. Given historical experience, Warsaw will sound the alarm over any possible entente between its two powerful neighbors. But no one has designs on Polish sovereignty; the last thing Berlin wants is to engage in a second Cold War on its eastern frontiers.

Collaboration between Berlin and Moscow makes a good deal of sense in the face of an uncertain strategic future. In a recent interview Ernst Uhrlau, head of the BND, Germany’s foreign intelligence service, spoke of a likely shift in the global balance of power resulting from the financial crisis. The BND chief made clear that Germany should prepare for a world in which Chinese influence could rise significantly. He also outlined a scenario of economic collapse and chaos, giving an unsubtle hint of the possibilities that await the West in the years ahead. Berlin will be looking for relevance and security in a Europe in flux. While contemporary Germany would hardly be a suitable candidate for the old Holy Alliance, a geopolitical partnership with Russia would be a net contributor to stability on the continent.

Otto got it right

U.S. policymakers no doubt will voice their concerns of developing Russo-German cooperation in dark undertones (for here we”d an alliance of not one but two nations that have yet to “overcome their pasts”). Much has been made of Berlin’s dependence on Russian natural gas, the newest supposed threat to the liberty of Europe. The U.S. is attempting to corner Central Asian energy and route it westward with pipeline initiatives (foremost among which is Nabucco) precisely to keep the Europeans within its policy orbit. If Washington can cut the Kremlin out of the energy equation, it would have greater freedom of action to pursue its encirclement of Russia without heeding German objections. With the U.S. now being outmaneuvered in Eurasia, rhetoric casting emergent Russo-German ties as a second Rapallo or Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact will become more commonplace.

Claims that Germany and Russia are enacting yet another sinister plot to snuff out “freedom” can be easily recognized as the polemics of liberal internationalists with their own agenda. Foreign policy conducted from Berlin today is a far cry from the Third Reich’s drive to global supremacy. Germany’s influential interwar school of strategic thought, Geopolitik, attained notoriety as a “Nazi science”. This was due to its role in providing Hitler a conceptual framework for world conquest. The school’s founder, Karl Haushofer, was a mentor of party leader Rudolf Hess and enjoyed his patronage until the latter’s mysterious one-way flight to Scotland in May 1941. Haushofer advocated an alliance between Berlin and Moscow that would shut Anglo-American sea power out of Eurasia.

While there is a superficial similarity between the continental outlook of Haushofer’s Geopolitik and deepening Russo-German ties, Berlin isn”t exactly resuming the quest for Lebensraum. The push for a comprehensive regulatory treaty on global climate change constitutes the extent of aggressive moves by Germany in today’s international arena.

Building better relations with Moscow is a bold move in line with a more traditional foreign policy stance, though it remains to be seen whether Germans can take the next step and affirm their own culture. Modern Germany is mired in the same dysfunctions rooted in philosophical liberalism that plague the entire West, from mass immigration and falling birthrates to the myth of total individual autonomy. The stereotype of jackboots and mass parades has been overtaken by efficient recycling programs and the enforcement of multiculturalist orthodoxy. Yet the national will to dominate cannot be meaningfully replaced by the will to self-destruction.

From the time of the Cold War, Germans have embraced becoming dutiful citizens of the European Union, tolerant and generous hosts of waves of third-world immigrants, and whatever else the currents of later modernity demanded. The 12-year nightmare of National Socialism is never far from the German conscience, in both the life of society and the formulation of policy. It is extraordinary that Berlin pursues any strategic interests at all under the unnatural weight of such a mindset. Germany is only beginning to overcome the paralysis induced by its role in the apocalyptic 20th century.