August 04, 2021

Usain Bolt

Source: Bigstock

The Olympics are a festival of human biodiversity. Different sports are best-suited to different body types: For example, swimmer Michael Phelps, winner of 23 gold medals, and eight-time gold-medalist sprinter Usain Bolt are roughly the same height, but Phelps has a long torso, like a human surfboard, while Bolt has long legs.

In turn, because humans evolved to have somewhat different body types in different parts of the world, that means that different racial groups have different athletic strengths and weaknesses, as you can see on NBC this week.

Granted, most whites aren’t physically much like Phelps and most blacks aren’t much like Bolt. But on average, whites are a little more long-torsoed and blacks are a little more long-legged. So, it’s not surprising that the greatest-ever swimmer is white and the greatest-ever sprinter is black.

And yet, according to America’s current conventional wisdom, as espoused by Dr. Ibram X. Kendi, all this can’t be true. Instead, evidence of superiority or inferiority in anything can only be the result of racist policy.

Although Kendi has been omnipresent in the media, as far as I can tell nobody has ever asked him about sports. The obvious racial gaps in various sports just never come up.

The most inarguable race differences can be seen in the simplest, most instinctual sport: running. All children naturally race to see who is fastest.

The big running news this week was that China’s Su Bingtian ran the race of his life to win one of the men’s 100-meter-dash semifinals in 9.83 to become the first runner without substantial sub-Saharan ancestry to qualify for the finals since the 1980 Moscow Games. That’s one out of eighty finalists.

Over the last ten Olympics, a black man has been over 400 times more likely to make the final than a nonblack.

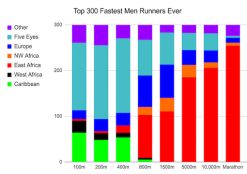

While almost all top 100m men have numerous ancestors from the Atlantic Ocean side of Africa, most of the leading distance runners in the world today were born in eastern Africa, such as 254 of the 300 fastest marathoners of all time.

While I might call this evidence for human biodiversity inarguable, that doesn’t stop many from arguing that only a Nazi moron would imagine that biological differences have anything to do with Olympic track results.

So, here’s a slightly stylized dialogue:

Q. What kind of unscientific bozo thinks genes matter? The only reason Usain Bolt won all those gold medals was that he trained so fanatically hard.

A. During this Olympics, one of the countless commercials featuring the now-retired Bolt embodies that line of thinking: A stentorian voice-over announcer orates that Bolt pushes himself to the limit “even if it means sacrificing everything.” At which point, the big Jamaican goof says, “Wait, what? I never lived like that,” and cracks open a cold Michelob Ultra.

Bolt set three world records at the 2008 Beijing Olympics while following a rigorous diet of nothing but 100 Chicken McNuggets per day.

The truth is that the 100 meters requires fewer hours of training per week than just about any other Olympic event. Carl Lewis worked out eight hours per week to get ready to win four golds at the 1984 Los Angeles Games. (Their regimens are extraordinarily intensive, however.)

That’s one reason why 100-meter women often show up at the starting line looking like female drag-queen impersonators, with huge nails, more than a few ounces of gold jewelry, and giant wigs: Their job leaves them with a lot of time on their hands for decorating themselves.

Q. Hey, idiot, if genes are all that matter for why Jamaicans run fast, how come nobody has ever even heard of a Nigerian sprinter, huh? Huh?

A. First, there are numerous top Nigerian (and other West African) sprinters. Among the 300 fastest 100-meter men ever, seventeen represented Nigeria, just behind Britain (eighteen), and of course Jamaica (36) and the U.S. (119). And that’s not counting Nigerians who run under other flags, like the 2004 silver medalist who moved to Portugal at 16, and the multiple Nigerians recruited by Persian Gulf satrapies like Bahrain and Qatar.

Second, nurture matters as well as nature.

Jamaica isn’t exactly Norway, but there are a lot of worse places to live: Life expectancy in 2018 was 74 years, while Nigerians could expect only 54.

Coaching is better in Jamaica. Bolt wasn’t the easiest runner to train, but at times when he was a teenager, it sometimes seemed as if the whole country was checking in to make sure he fulfilled his potential.

Similarly, a lot of expertise might be needed to compete at the very highest levels and not test positive. Jamaicans are plugged into the American college track team recruiting network, so their coaches are likely sophisticated in the dark arts. Despite the “No problem, mon” stereotype of Jamaicans, their officials appear to be fairly diligent and competent at avoiding scandals, at least so far. (Bolt did get his 2008 4x100m relay gold taken away in 2017 when a teammate was retroactively disqualified.)

(It may help that the Jamaican government is not likely to put its national heroes in jail the way the U.S. government sent 2000 Olympic heroine Marion Jones to prison for lying to a federal agent who asked her about her PED use, which has to be discouraging. It’s perhaps not a coincidence that Jamaica pulled ahead of the U.S. in sprinting soon after.)

In contrast, Nigerian sports officials are notoriously inept and unhelpful. When sprinter Blessing Okagbare was disqualified for human growth hormone after winning her first round of the 100-meter competition, she ripped Nigeria’s sports establishment that did not protect her.

She may have a point. Ten other Nigerian athletes were disqualified in Tokyo not because they tested positive but because their federation back home hadn’t organized enough out-of-competition drug tests for them. Whether that was out of Machiavellianism or laziness is hard to say.

An important question that I’ve never seen researched is whether racial groups might respond to PEDs differently. One possibility is that the elaborate drug testing system just keeps everybody at a reasonable baseline without maniacs killing themselves in pursuit of a medal. So perhaps more or less the same people win, just in faster times. But if human biodiversity extends to respond to PEDs, well, who knows?

Q. The reason Jamaicans run the 100m and Kenyans the marathon is solely because of colonialist stereotypes about what they’d be good at.

A. This might sound plausible if there were no other distances. But of course, track offers a ladder of events at multiple distances. Coaches are constantly trying to see if their runners could excel at longer or shorter distances.

The 6′ 5″ Bolt, for instance, was originally envisioned as a 400m runner because it was assumed that his height was not compatible with the shorter, more start-intensive races. But he preferred the 200m and begged to be allowed to run the 100m. His coach said he could try the 100 if he broke the national record in the 200. He did, and in his fifth 100 ever, he set the world record.

And other runners move up to longer races as they attempt to find out their natural strong suit.

As it turns out, people of western African descent tend to be best from 100 to 400 meters, with a quick falloff after that. In the top 300, there are 22 Jamaican quarter-milers (400m) and eight Nigerians, but at 800m only one Nigerian and zero Jamaicans. And no Caribbean or West African runners from any country are in the top 300 at any length longer than 800m. In contrast, there are eleven Kenyans among the 300 best at 400m, but eighty at 800m (and 152 at the marathon).

What’s the reason for the 400m vs. 800m divide? Sports scientists say that’s where physical demands switch from more anaerobic to more aerobic. One weekly training plan, for instance, tells 800m men to run 48 kilometers per week on the roads, plus sprint training on the track. In contrast, quarter-milers are never expected to run more than twenty minutes in a single day.

In Kenya, the average life expectancy is 66 years, and the runners tend to come from the healthiest parts. Kenyan runners tend to come from the Kalenjin people, who have been evolving culturally and genetically as a sort of horseless cowboys on the high-altitude grasslands.

This helps make the 800m the most diverse Olympic track event, with West Africans, Europeans, Northwest Africans, and East Africans all having a chance to medal.

Interestingly, the second East African power, Ethiopia, skews even longer than Kenya. Only two Ethiopians are among the best at 800m, but 21 at 1500m and 92 at the marathon (42,000m).

While Kenyan runners tend to be black and elongated, Ethiopian runners tend to be brown and short. They come from even higher farmlands than the Kenyans, sometimes over 10,000 feet elevation. The thin air is good for both genetic selection and intensive training.

“Five Eyes” refers to the spy consortium of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, U.K., and U.S., or what French presidents denounce as the “Anglo-Saxon” powers.

Northwest Africa means the olive-skinned athletes of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, such as 2004 Olympic standout Hicham El-Gerrouj. Their strengths run from 800m to 10,000m but can’t seem to withstand the East African juggernaut in the marathon.

Q. Why do you want to know hatefacts like these anyway?

A. They seem interesting and important. All truths are connected to each other, while all lies are dead ends.