August 22, 2015

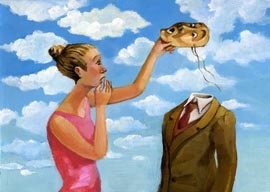

Source: Shutterstock

As it happens, I would be perfectly capable of writing a strong, or at least plausible, refutation of my own position. Indeed, I think I could put the counterarguments (which undoubtedly exist) very strongly. I once wrote two articles under different names for the same newspaper in which I put forward the arguments both for and against some proposition or other, with almost equal passion, eloquence, and logic: At least, nobody noticed that the articles for and against were written by the same person.

I suppose this is all perfectly normal for lawyers who have to argue the best case they can on behalf of their clients short of telling outright lies on their behalf. It must be a habit with them to argue in court what they don”t believe and to try to refute what they do believe and therefore, if they are successful in their arguments, to see injustice done. Whether this dialectical suppleness, or deviousness, spills over into their private life, I do not know; I know of no studies (though they may exist) that demonstrate the honesty or otherwise of lawyers by comparison with others of their level of intelligence and education.

Perhaps one of the reasons, then, that we defend our opinions with such ferocity against contrary opinions that we fear may have some truth or evidence in their favor is that we fear to lose the very idea of truth itself. If we find ourselves in a position to argue both sides of a case with equal facility, we may become mere cynics or sophists.

Bacon begins his essay “On Truth” as follows:

What is truth? said jesting Pilate, and would not stay for an answer. Certainly there be that delight in giddiness, and count it a bondage to fix a belief; affecting free-will in thinking, as well as in acting.

It is thus to avoid that giddiness of which Bacon speaks that we sometimes find ourselves passionately defending the only partially defensible, and defending a particular untruth in the interests of Truth itself.