October 14, 2015

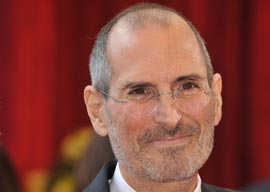

Steve Jobs

Source: Shutterstock

Steve Jobs, the superbly theatrical film about the Apple cofounder’s turbulent mid-career arc, opened in Los Angeles and New York over the weekend to the best per-theater grosses since American Sniper.

It looks as if it will be another upmarket hit for screenwriter Aaron Sorkin in the tradition of his 2010 Mark Zuckerberg biopic The Social Network and his 2011 Billy Beane biopic Moneyball. Both were book adaptations that sounded close to impossible to turn into comprehensible movies.

We are supposed to be living in an age of great television and weak films. But when given his own television shows with ample hours of airtime to fill with his earnest opinions, such as Sports Night, the Clinton White House fantasy The West Wing, Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, and The Newsroom, Sorkin tends to be insufferable.

On the other hand, when Sorkin is brought into a movie production as a hired gun and told to somehow cram a technical topic that he doesn”t necessarily care all that much about, such as Moneyball‘s revolution in baseball statistics, into a two-hour screenplay, he’s a master of middlebrow.

The quality of Sorkin’s screenplay for Steve Jobs suggests that he has perfected a new genre of movie: the informative business-executive biopic. You could call it the Frequent Flyer Movie.

To me, the term “middlebrow“”in the sense of a story being educational as well as entertaining”is high praise. When browsing in the airport bookstore, the kind of guy who racks up 100,000 miles per year on the corporate credit card wants something that will be diverting but might also sneak in some new way of thinking that could help him on the job.

It’s not easy to write novels or movies about business. I spent 18 years in corporate life, and often pondered how I might convert my extensive knowledge of consumer packaged goods marketing into a best-selling novel. But at that point I was always stumped by the fact that business fields are so abstruse that they are difficult to make interesting or even understandable to the public. If the industry was fun and simple, then everybody would do it and there”d be no money in it. To convey the lessons I learned working at the most successful and controversial start-up of the 1980s in the market-research business, I”d have to tell you more about Universal Product Code sales data than you”d care to know. I always got to the point of conceding that I”d have to make my novel a murder mystery just to have any chance of getting it published.

And then I”d give up.

In contrast, Sorkin’s adaptations leave out fictitious violence”although Steve Jobs includes a scene in which Jobs hints to the needy mother of Lisa, his intermittently unacknowledged illegitimate child, that he knows people who know people who could have her rubbed out. Instead, Sorkin plunges into explaining the corporate and technical issues through dialogue.

The reason Sorkin’s television shows are tiresome while his movies are brilliant is redundancy. Sorkin repeats himself. He uses and reuses the old screenwriting trick of “plant and payoff.” In a two-hour movie, Sorkin’s repetitiousness serves to get complex ideas across, but in a multiyear TV series it just becomes much too much.

His Steve Jobs exemplifies Sorkin’s awareness that audiences need reiteration with variation if they are to follow along. Sorkin, who started out as a playwright, constructs a backstage drama in which each of the three acts consists of the 40 minutes before Jobs goes on stage to launch a new product. Although it’s not terribly funny, the three-act structure of Steve Jobs is reminiscent of that apogee of British farce, Michael Frayn’s Noises Off, in that almost exactly the same things happen three times, but with continual twists that deepen our understanding.

The 54-year-old Sorkin is the ultimate baby boomer, which makes Steve Jobs even better than The Social Network. For all of The Social Network‘s brilliance, it was hard to avoid noticing that Sorkin’s screenplay, which was ostensibly about the founder of Facebook, was more about Sorkin’s own insecurities. (For example, Sorkin’s assumption that Zuckerberg must have felt like an ethnic outsider at WASPy Harvard was eye-rolling.)

But Sorkin, who wrote his first play, A Few Good Men, on cocktail napkins while bartending and then transcribed it on a second-generation Mac 512K, understands Jobs far better. Moreover, he has Walter Isaacson’s wise 2011 authorized biography of Jobs to draw upon. (Here’s my review of Isaacson’s bio.)

While most people today recognize Jobs for the mobile devices (iPod, iPhone, iPad) of the amazingly lucrative last decade of his life (1955″2011), Sorkin focuses upon the mogul’s least successful era, 1984″1998, when he wrestled with getting right the graphical interface on desktop personal computers.

The first act is the introduction of the Macintosh two days after Ridley Scott’s “1984“ commercial aired during the broadcast of the 1984 Super Bowl:

On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you”ll see why 1984 won”t be like “1984.”

The irony is that if Jobs, with his obsession with closed architectures in contrast to the IBM PC’s laissez-faire open system, had lived to enjoy another decade as dominating as his last, he would have become Big Brother himself.

Perhaps that was his plan all along?

By bringing the same historical figures back three times, Sorkin painlessly induces the audience to learn ever more about the history of the world’s highest market-capitalization company. In each act, Jobs squabbles with his colleagues Steve Wozniak (inventor of the Apple II, which was more or less the first personal computer), Andy Hertzfeld (who wrote the system software for the Mac), and John Sculley (the father figure he lured from Pepsi to help him run Apple).

The ursine Wozniak is played by Seth Rogen, who is decent but a little too Seth Rogenish to be cast as such a beloved supporting figure. Hertzfeld is portrayed well by Michael Stuhlbarg, the much-put-upon physicist father in the Coen brothers” A Serious Man. And Sculley is undertaken by Jeff Daniels, who is not quite as awesome in his now-familiar role as the Head White Guy in Charge as he is in Sir Ridley’s The Martian.

The casting as Jobs of Michael Fassbender, who in the X-Men movies plays Magneto, the mutant civil rights leader set on exterminating humanity, has its advantages and disadvantages. First, Fassbender, as was Jobs, is a commanding star. Fassbender would be perfect to play the U-boat captain in a reboot of the 1981 film Das Boot.