December 30, 2012

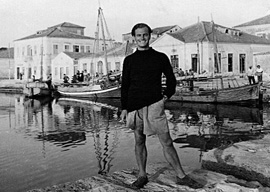

Patrick Leigh Fermor

He augmented his Byronic life-legend by fighting with the Cretan resistance during the war and masterminding the 1944 abduction of a German general”an exploit commemorated in the 1957 Powell & Pressburger film Ill Met by Moonlight. Then he devoted the rest of his life to building his and his wife’s ideal house at Kardamyli on one of the Greek mainland’s southernmost tips. (John Betjeman swooned that the living room was “one of the rooms in the world.”) He also continued traveling.

Apart from the two European books (a third will finally be published next year as The Broken Road, reworked by Artemis Cooper from an early draft), he wrote about Greece (Mani, Roumeli), the Caribbean (The Traveller’s Tree, The Violins of Saint Jacques), monasteries (A Time to Keep Silence), and South America (Three Letters From the Andes) and turned out impossibly elegant review-essays. His last publication was in 2008, a collection of his correspondence with the Duchess of Devonshire (In Tearing Haste).

A painfully slow, easily distracted writer who was often bumptious and careless with other people’s money, he nonetheless contrived to lead an extravagant existence, moving in glitteringly gifted circles. He made almost no enemies in the course of 96 years (he died in 2011) except for hardline communists who tried to kill him in 1979, and in England a few less dangerous but equally unappetizing reviewers who disapproved of his maleness, class, and intellectualism. He had a chivalric understanding even with the abducted General Kreipe, with whom he exchanged Horatian snippets as PLF’s party took their prize furtively through the Cretan uplands to rendezvous with a British boat. Even a blood feud that commenced when he killed a resistance fighter by accident was eventually resolved in a flurry of ouzo and embraces from the dead man’s nephew, mixed with kindly offers to dispatch anyone Leigh Fermor wanted dispatched.

Artemis Cooper is Leigh Fermor’s first biographer, and she is well-placed to offer insights. If anything, she may be too close to her subject. Her grandmother, Lady Diana Cooper, was a close friend of Leigh Fermor’s, and the author has halcyon memories of childhood visits to Kardamyli, stroking the Fermors’ pet dog while listening entranced to its master’s stories.

She has done an excellent job of narration, whether she is telling us about London’s literati, Moldavian manors, Irish venery, or PLF’s venereal disease. If at times the reader feels he is not really getting under PLF’s skin, it is almost certainly due to a paucity of confessional source material rather than Cooper’s shortcomings as researcher or collator. Leigh Fermor’s generation did not weary the world with self-analysis; they just did things, quietly or showily according to taste. As Stephen Spender once observed, PLF was clearly “not an empathizing introvert.” That is not to say there are no revelations or inspired guesses in what could have been hagiography”the author senses when her self-romancing subject was being economical with the actualité, such as when she discloses his ignoble interlude as hosiery hawker around west London.

It would have been fascinating to know whether he ever came to any conclusions about all the wonderful things he had seen that mostly disappeared within his lifetime. He may not have been an empathizing introvert, but he must surely have fretted about Greece, England, and Europe’s future. Just as Joan and all his friends fell away during his life, leaving him a lonely relic, so too his vibrant Europe has dried up and diminished under the pressures of centralization, communism, fascism, globalism, homogenization, immigration, internationalism, rationalism, and technology. We read him as raconteur and stylist rather than as oracle, yet had he written of these things many would have paid attention. As we close the book at the end of his epic adventure, we are left wondering whether at the end the winsome Wändervogel was really content.