July 07, 2011

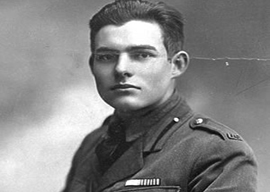

Ernest Hemingway

Exactly fifty years ago last Friday night going into Saturday morning—July 1st into the 2nd—in Ketchum, Idaho, Ernest Hemingway asked his wife Mary to sing an Italian song, “Tutti Mi Chiamano Vionda” (“Everyone Calls Me Blondie”), and after they both went up to bed he silently crept down the stairs, stepping softly so as to make no sound, went to the basement storage room, took out a double-barreled shotgun, inserted two shells, went back up to the foyer, leaned against the hard steel with his forehead, and pulled the trigger. The newspapers reported it as an accident. I read about it the next day in my aunt Sophia’s garden in Athens and decided then and there that the writing life was the one for me.

Fifty years might seem a lifetime to you young whippersnappers, but it’s only yesterday to me. How clear it still is. The great man, unable to live up to his title as the literary world’s heavyweight champion (Norman Mailer’s invention), goes out like a champ—with a bang. He’d been in the wars too long. And it was a graceful exit despite the mess. An overdose wouldn’t have been his style. In Papa’s fiction, tragic heroes died by bullet, like the Swede in “The Killers,” who is warned by Nick Adams that two pros are in town to kill him, but who stays in bed, looking at the wall, tired of running. Papa is out of fashion now, but so is sportsmanship, manhood, gallantry, even heterosexuality, and especially Christianity.

What is there to say about Hemingway that hasn’t already been said or written? He was the first literary pop star before the p-word was invented. He wrote about the beautiful active life, the tranquil exhilaration of fishing, but also about the brutality of big-game hunting, bullfighting, and war. He resolved this dissonance in art by turning writing into marvelous prose. His masculine prose had the effect of the utmost subtlety. It was the hardest way to write because it seemed so easy and natural. Literary types called it non-literary and vulgar—in the beginning. But Papa was following his idol, a certain Mark Twain, who was never one to follow literary conventions. After The Sun Also Rises became a great hit, men started to talk the way he wrote. “Have a drink” became a watchword. Heroic dissipation turned into a lifestyle for romantic wannabes.

Hem was criticized for glorifying and making martyrs of bullfighters—Edmund Wilson, a Papa fan, called it neurotic and drunken—but Papa gave back as good as he got: “Bull fighting is not a sport. It was never supposed to be. It is a tragedy. A very great tragedy. The tragedy is the death of the bull. It is played in three definite acts.” I once discussed Papa with Luis Miguel Dominguin, one of the five greatest matadors ever. (The others were Joselito, Belmonte, Manolete, and Ordoñez.) He didn’t like Hemingway, whom he said knew nothing about bullfighting. Dominguin knew much more, I am sure, but the fact that Hemingway called Louis Miguel’s brother-in-law Antonio Ordoñez the greatest ever must have played a part.