September 27, 2012

I had my weekend nicely planned. Saturday: small catch-up stuff, paperwork, and household repairs. Sunday: Write a book review I’d promised for midnight deadline…oh, and read the book.

Friday afternoon a friend called: “I have a spare ticket for the dress rehearsal of Turandot tomorrow, eleven AM; wanna come?”

I very much wanted to, so I did. Dress rehearsals tend to come with a couple of 45-minute intermissions, though. It takes two hours to get from my house to the New York Metropolitan Opera. Add in a leisurely lunch with my friend washed down with a few glasses of wine, and there’s a whole day shot.

I couldn’t miss Turandot, though. Opera-wise, I’m a meat-and-potatoes guy. I like the big old classics, the ones that make up most of the Met’s season schedule. If you are a fan of Karlheinz Stockhausen or Thomas Adès, I have no quarrel with you. We are just, as the late Stephen Jay Gould said of religion and science, operating under different magisteria. Or as a great novelist remarked: “One half of the world cannot understand the pleasures of the other.”

Turandot is one of those big old classics”the last one, really, by date of composition. (The composer died in 1924 with the final act’s last half still unwritten. A lesser talent completed it.) Turandot also has some nonmusical appeal: It gives set designers the opportunity to let out their inner Cecil B. DeMilles. The current Met production shows the result magnificently.

Like most of those big old masterworks, though, it’s sappy and silly. The sappiness is a consequence of opera having come to full maturity in the Romantic Age from 1800 onward. With all the beauty of the music, the voices, and the sets, there comes a point in every opera where I find myself thinking: “Oh, come on!”

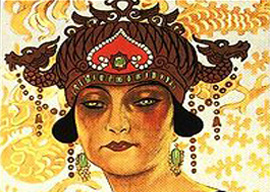

With Turandot that point comes at the very end. The title character is a beautiful but cruel Chinese princess. To win her hand, suitors have to answer three riddles. Those who fail”all have so far”die gruesomely, to her apparent pleasure.

Along comes a handsome stranger who answers the riddles correctly, so by the rules Turandot must marry him. She hates the thought of it. Not wanting an unwilling bride, the stranger gives her a second chance: If she can find out his name by dawn tomorrow, she can impale, disembowel, burn, or decapitate him.

During the night they meet and he woos her. Confident he has melted her icy heart with the Power of Love, he tells her his name: Calaf. Since the sun hasn’t yet risen, he’s handed the victory to her.

Off they go to report to the emperor, Turandot’s dad. “Noble father, I know the stranger’s name!” exults Turandot. Pause for some dramatic tension. “His name is…Love!”

Oy.