March 08, 2023

Source: Bigstock

Perhaps because this has seemed like the coldest winter I can recall in normally balmy Southern California, I got to wondering: Why do northerners tend to be smarter than southerners? Is it because of the north’s cold winters, as Charles Murray, a son of Iowa, recently suggested on Twitter?

To me, the core truth of the cold winters theory is this: humans in places where temperatures get lethally cold all die, 100%, unless they figure out ways to stay warm. There’s no other comparably ruthless environmental demand.

If in late February I’d driven up to Big Bear Lake at 7,000′ elevation in the San Bernardino Mountains for a little skiing and then found myself blizzarded in for the last twelve days by ten feet of snow, would I have dealt with this challenging situation with impressive foresight and industry?

No, of course not: I’m a SoCal doofus, a Valley Dude. I don’t know anything about what to do under 115 inches of white stuff.

Before speculating about the reasons that a north-south gradient in cognitive test scores exists, let me show that it does.

Northern (or the rare antipodean) countries tend to average higher on cognitive tests and their correlates, such as GDP per capita. The same overall pattern is true for American states.

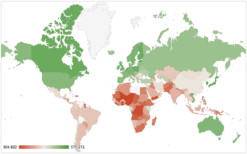

Below, I map the World Bank’s database of Harmonized Learning Outcomes, which aggregates a half-dozen global and regional school achievement tests, such as the well-known PISA and the obscure PASEC in West Africa. Dark green is high and dark red low:

The scores are calibrated in the manner of the American SAT college admission test, with 500 representing the average in the wealthy OECD countries, with a standard deviation of 100.

The highest average score, 575, is found in equatorial Singapore. But that island country is dominated by Overseas Han Chinese with roots in northeast Asia. The lowest score, 304 (2.7 standard deviations lower), is found in fast-growing Niger in the sweltering Sahel.

Of course, there are numerous exceptions to the pattern that the further from the equator, the higher the average test score. And the north-south trend doesn’t necessarily hold up within large countries.

For example, the Chinese love regional stereotypes, and one of theirs is that southern Cantonese speakers are more mentally energetic than the slower-thinking northern Mandarin speakers.

In India, the software industry is concentrated in Bangalore in the south, while the “deep north” along the Ganges can be depressingly uneducated.

Within Germany, the lucrative Bavarian Motor Works is in, no surprise, Bavaria down south.

But overall, the correlation between the World Bank’s fairly noisy estimate for test scores and the latitude of each capital city across 174 countries is, I calculate, a pretty strong r = 0.62.

That northerners tend to outscore southerners is also true within the United States. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-NY), a lapsed social scientist, pointed out in his 1992 Moynihan’s Law of the Canadian Border:

I was allotted two minutes in a gathering of Democrats last week to explain, yet again, that there is simply no significant connection between school expenditure and pupil achievement…. “Fellow countrymen!” I exclaimed. “If you would improve your state’s math scores, move your state closer to the Canadian border!”

Please, I asked, get me the correlation between math scores and distance of state capitals from the Canadian border. Back came the answer. A negative 0.522—which may be the strongest correlation known to education, and which means that the further a capital is from the border, the lower its test score. By contrast, the correlation between expenditures and math tests is a paltry 0.203.

Of course, a large part of Moynihan’s joke is that warmer-weather states in the south have more blacks and in the southwest more Latinos.

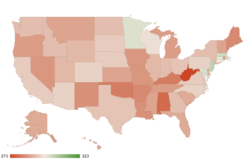

If you look at 2019 NAEP eighth-grade math scores just for white students, the Moynihan Effect is more muted. But yes, Minnesota whites do outscore Mississippi whites:

So, what’s going on?

One widespread belief is that warm weather makes humans decadent. In the 20th century, it was commonly assumed that when upright Iowans move to Los Angeles, they go soft in the sun.

Lately, as California has gotten stringently expensive, you hear that more about Floridians: When a hardy upstate New Yorker moves south, he turns into a goofball Florida Man. (One no-fun counter theory is that every state has its own Florida Men, but Florida’s open government laws mean that stories about its losers’ screwups wind up in the newspapers more.)

These prejudices about the residents of different American states tend to lean toward the socially acceptable nurture side of the nature-nurture divide.

In contrast, Murray’s winter argument outraged many on Twitter because it seems like not only a theory of culture but also a not-implausible explanation for why genetic differences might evolve between continental-scale races. If cold winters select for the foresight needed to survive them, then over enough time they ought to foster not only more prudent customs but the Darwinian natural selection of genomes as well.

Logically, the policy implications of the genes vs. environment debate would appear to be the reverse of what everybody who condemns Murray assumes: If the reason that black men have an extraordinarily high homicide rate and rather low hours worked is solely cultural, then our society ought to be working an awful lot harder to change their culture for them than it has been since George Floyd. But if they can’t help it genetically, then the fashionable hands-off, laissez-faire attitude toward black criminals carrying illegal handguns found among Soros district attorneys might make sense.

Note that it’s inherently challenging to distinguish between the effects of nature and nurture. Successful progenitors usually pass on both their genes and their cultures, so disentangling the effects of nature vs. nurture has been one of the major-league venues of intellectual endeavor for over a century.

It’s perhaps worth noting that Ryan Coogler, director of the celebrated superhero movie Black Panther, seems to subscribe to some version of Cold Winter theory. After visiting Lesotho, an enclave constitutional monarchy within South Africa that is at such high altitude that it has a ski resort, Coogler set his African technological utopia of Wakanda so far below the equator and at such elevation that much of Black Panther’s action takes place above the snow line.

Perhaps Coogler’s backstory for Wakanda is that if the Bantu Expansion out of Nigeria and Cameroon had reached southerly Lesotho several millennia earlier, blacks would have had time to evolve northern levels of technological capability.

But are cold winters a truly unique selection filter?

I’m not so sure.

First, note that almost all African-Americans are the descendants not of hunter-gatherers such as Pygmys and Bushmen, but of Iron Age Bantu farmers.

Second, they used iron hoes for weeding, so their community had to master iron-smelting. Whether sub-Saharans independently invented iron-making or learned it from North Africans remains in dispute, but the know-how to make iron tools has been widespread south of the Sahara for more than 1,500 years.

Third, African farmers typically don’t live in some kind of season-free environment in which they can carelessly sow and reap whenever they are in the mood. Instead, they must deal in timely fashion with their wet seasons and dry seasons.

All that said, the physical environment in Sweden still sounds more challenging than in Kenya, but it’s more a matter of degree than of kind.

Or it could be that Sweden actually has an easier climate due to winters killing off many germs. But then again, perhaps a Swedish winter is less random in its harmful effects than is malaria and thus better at imparting useful lessons.

What might be a more fundamental distinction between African and Eurasian farming is which sex does most of the work.

As anthropologists like Jack Goody and Ester Boserup have documented, a big difference between sub-Saharan and European agriculture is the type of soil. Europe leans more toward rich, heavy dirt, while Africa’s dirt is, on average, lighter.

Thus, the archetypal European way to weed is to plow the fields, which was almost always man’s work due to its demand for upper-body strength. In contrast, African fields were traditionally weeded with iron hoes wielded by women.

Hence, in Africa, a much larger fraction of the farmwork is performed by women than in Europe. In turn, because wives did more of the work to keep their children fed, they had more options in choosing their children’s fathers than just looking for good providers, being more able to afford to opt for men who were better athletes, entertainers, or lovers than wage-earners.

As I recently demonstrated using Harvard economist Raj Chetty’s data, the earnings and imprisonment gaps between white and black women are only moderate in size (thus debunking the reigning theory of intersectionality that black women must be the most victimized of all by the dominant culture). The root of America’s race problem instead is the underperformance of black men.

There are various theories about why this gap is so large. Of course, the only rationalization that is respectable in polite society is that it is all the fault of whiteness, which must be abolished.

But the Occam’s razor explanation would be that in mating, as in farming, you reap what you sow.