February 26, 2009

Before he was a world-rebuilding, race-transcending international statesman, our president had become well acquainted with the Chicago Way.

And they tell me your are crooked and I answer: Yes, it

is true that I have seen the gunman kill and go free to kill again.

~Carl Sandburg, “Chicago,” 1916

When Rudyard Kipling saw Chicago in 1891, he wrote, “I urgently desire never to see it again. It is inhabited by savages.” Twenty years later, a losing candidate for mayor complained, “Chicago is unique. It is the only completely corrupt city in America.” Socialist leader Eugene Debs called it “unfit for human habitation.” Mike Royko, the Windy City’s columnist-conscience until his death in 1997, suggested that “the city slogan be changed from Urbs In Horto, which means “City in a Garden,” to Ubi Est Mea, which means “Where’s mine?” “ Journalist Walter Winchell called the inhabitants “Chicagorillas.” Chicago nonetheless had its defenders. The actress Sarah Bernhardt said after performing there, “It is the pulse of America.” H. L. Mencken declared it “the Literary Capital of the United States.” And Norman Mailer, who condemned its politicians in Miami and the Siege of Chicago in 1968, wrote, “Perhaps it is the last of the great American cities.”¨” To Frank Sinatra, it would always be “that toddlin” town.”

Chicago’s most recent claim to singularity is its gift to the nation of Barack Hussein Obama. It seems surprising that no Chicagoan before him had seized the White House, given Chicago’s significance in national electoral politics. One measure of this importance is that the Republicans and Democrats have held more presidential nominating conventions in Chicago than in any other city”twenty-five, compared to ten for its nearest rival, Baltimore. Chicago’s clout and money were always welcome in national elections, even if its politicians were not sufficiently potable to sit uptable from the White House salt. Jack Kennedy said that he would not have won in 1960 without Chicago Mayor Richard Joseph Daley, a fellow Irish Catholic and old friend of Kennedy’s father. (When Illinois Republicans demanded a recount in 1960 of the famously unreliable Cook County vote, Daley agreed to check all the ballots at the rate of one precinct a day. “At that pace,” wrote Mike Royko wrote in his magisterial biography, Boss: Richard J. Daley of Chicago, “they would complete the recheck in twenty years.” A special prosecutor, who turned out to be a “faithful organization Democrat,” eventually dropped all charges against the accused polling officers.) Bill Clinton was so indebted to the second Mayor Daley, Richard Michael, that he made his younger brother William secretary of commerce.

Chicago’s politicians were kingmakers, not kings. Their legendary delivery of delegates at the Democratic Convention and electoral college votes to the Democrats” nominee required Democratic contenders to feign ignorance of the ways the votes were obtained and counted. Although the last time police had to seize large quantities of arms from polling places was in 1924, the number of dead who went on casting votes meant every Chicago election was called Resurrection Day. Yet electioneering was governed by explicit regulations, as Fortune magazine noted in August 1936: “Rule one of this art: never pay a bum his dollar for a full day’s voting in advance. He may drink it up before he has voted the requisite number of times, in which case he will spend the day sleeping it off.” Quaint electoral traditions, abolished by reformers in most other American cities by mid-20th century, made Chicago politicians a hard sell for national office. Even the saintly Adlai Stevenson could not overcome his identification with the Machine to beat Dwight Eisenhower for president in the 1950s.

Obama changed that, his achievement of becoming the first president of African descent less startling than being the first from Chicago.

At his inauguration on January 20th, Obama vowed to “remake America.” His devoted supporters were entitled to ask whether he remade Chicago during his twenty-one years there, three as a community organizer and eighteen as a lawyer and politician. Or did Chicago make him? He saw Chicago for the first time aged ten, when his grandmother determined the precocious Hawaiian islander should visit the mainland. His memoir, Dreams From My Father, mentions only three images from this three-day stay: the indoor swimming pool at his motel, the elevated train he stood under while shouting as loud as he could and “two shrunken heads” in the Field Museum that struck him as “some sort of cosmic joke” from which his mother had to pull him away. That would have been in 1970, Richard J. Daley’s sixteenth year as mayor.

Fourteen years later, Obama completed his undergraduate studies at Occidental College in California and Columbia University in New York. He wanted to change the world by organizing communities. His rationale was as idealistic as it was simple, or simplistic:

Change won”t come from the top, I would say. Change will come from a mobilized grass roots.

That’s what I”ll do. I”ll organize black folks. At the grass roots. For change.

The capital of urban activism in America was Chicago, probably because there was much to be active against. Organizers like Jane Addams and Saul Alinksy aimed at the realistic target of winning concessions from a corrupt power structure, rather than the more problematic goal of eliminating it. “Community organizing against the political establishment is a fundamental tradition in Chicago,” the left-liberal political consultant and columnist Don Rose told me recently in Paris. With “Another Old White Guy for OBAMA” badge pinned to his jacket, the seventy-eight-year-old savant recalled Saul Alinsky’s methods. Rose knew Alinsky, author of the 1946 bestselling Reveille for Radicals. Although the father of Chicago community organising died in 1972 at the age of sixty-three, Rose spoke of him in the present tense,

When Alinsky threatens to take three trainloads of black people to Marshall Field’s department store, he’s not trying to shut down Marshall Field’s, but to get it to hire blacks for various jobs. Or to bring legislation. Or to build a new police station, a new fire station. A kind of petitioning with the threat of force.

Obama admired him so much that he contributed a chapter to a book about him. (Hillary Clinton wrote her graduate thesis at Wellesley College on Alinsky, one of the few interests, apart from the pursuit of power, she shares with her new boss.)

Soon after his 1983 graduation from Columbia University, Obama applied to work for civil rights and community groups in Chicago. In the absence of any response, he became a researcher for corporate consultancies in New York. Two years later, a community organiser from Chicago approached him and asked what he knew about the place. Obama answered, “Most segregated city in America.” That apparent fact did not deter him from accepting a post in the tough South Side neighbourhoods where blacks had been ignored, abused and exploited for generations. “A week later,” Obama wrote, “I loaded up my car and drove to Chicago.”

* * * * * * *

Chicago has been a one-party city since 1931, when the Democrats captured city hall. Their monopoly outlived that of Italy’s Christian Democrats, who ruled in collusion with the Mafia and the Roman Catholic hierarchy in ways the average Chicago ward boss would find familiar, by thirty-four years. Despite beating the Soviet Communist Party’s seventy-four year record four years ago, Cook County Democrats have yet have their glasnost. The Democratic monopoly is so secure that the only elections that matter are the Democratic primaries, a Republican having as much chance to become mayor as Ralph Nader does of moving into the Oval Office. The Cook County Democratic Party provided Obama, when he arrived from New York in the summer of 1985, more instruction on achieving and using power than Saul Alinsky’s manuals. It all began with Anton Cermak, an immigrant from Bohemia who, like Obama, had the ostensible defect of a “funny name.”

“Tony” Cermak graduated from precinct captain to chairman of the Cook County Democratic Party Central Committee in 1928 and took the mayor’s office from the Republican incumbent, William Hale “Big Bill” Thompson, three years later. Thompson, who counted Al Capone among his many friends, had made the mistake of campaigning against Cermak’s foreignness. One slogan went,

I won”t take a back seat to that Bohunk, Chaimock, Chermack or whatever his name is

Tony, Tony, where’s your pushcart at?

Can you picture a World’s Fair mayor

With a name like that?

Cermak replied in terms that Obama might have used in 2008: “It’s true we didn”t come over on the Mayflower, but I came over as soon as I could.” Cermak carried the Chicago black vote by stealing the city’s leading Negro politician, William L. Dawson, from the Republican Party. Dawson had lost a leg in France during World War I, and like most blacks born in the South belonged to the party of Lincoln rather than the party of lynching. Cermak promised him an alderman’s seat, and he delivered his black constituents to the Democrats from then on. Chicago’s electoral arithmetic was simple: Democratic committeemen in the city’s fifty wards controlled captains of the 3,500 precincts, who got out the vote with promises of jobs”the mayor had at least 30,000 from the city payroll in his gift. “Tony was always careful to put a Jew, a Czech, a German, an Eyetalian, a Swede, a graduate from the University of Chicago, someone close to Hull House [Jane Addams’s settlement house for social reform], and a friend of the big bankers somewhere on his elective or appointive or advisory slate,” Fortune wrote. It added, “Police reporters say Tony employed twenty-six stool pigeons to spy on his own organization. He took no chances.”

Unfortunately for poor Tony, chance did not favour him in early 1933 when an assassin took aim at President-elect Franklin Delano Roosevelt in Florida and killed Cermak by mistake. His coalition survived with the solid block of black votes from Dawson’s South Side precincts. Two Irish mayors named Kelly and Kennelly, creatures rather than masters of the Machine, served until 1955. Then, fifty-three year old Richard J. Daley”who had taken Cermak’s old post as head of the Cook County party two years earlier”came in with no intention of leaving.

Daley held on, winning four re-election contests, until his death. Daley’s reputation was as an honest man who took Communion daily at his parish church and never stole a penny. He tolerated corruption among his friends, until they were foolish enough to be arrested. He lived in a modest house only a few blocks from the one where he was born in working class Bridgeport. He took care of his own. He arranged, as George W. Bush’s father had, for his sons to avoid combat in Vietnam by putting them into reserve units that never left home. When one of his sons went to work for an insurance company, Daley gave the firm the city’s lucrative insurance business. Like Bush Jr., he was famed for his sometimes revealing misuse of language: “Today the real problem is the future.” “We shall reach greater and greater platitudes of achievement.” “They have vilified me, they have crucified me; yes, they have even criticized me.”

After his policemen beat demonstrators and a few journalists senseless during the Chicago Democratic Convention of 1968, he said, “Gentlemen, get the thing straight once and for all”the policeman isn”t there to create disorder, the policeman is there to preserve disorder.” The Machine he ran was crooked, as were the cops. His police force was run by political cronies, and everyone knew that it was easier to tip a cop $20 than to pay a speeding fine. If that had been all there was to Daley, however, he would not have been re-elected the first time, let alone the subsequent three. He assiduously practiced his prescription that “Good government is good politics.” Daley was a builder of great public projects and abysmal ghetto tower blocks. If Chicago is one of the most beautiful cities in America, that is as much his legacy as the police’s record of torturing black suspects and, in 1969, assassinating two leaders of the Black Panther Party in their beds.

In the 1963 elections, when Kennedy stopped at O”Hare Airport to endorse him, Daley lost the city’s white vote for the first time. But the black vote, thanks to William Dawson, who had been the Machine’s man in Congress since 1943, gave him his third term. Mike Royko wrote,

The people who were trapped in the ghetto slums and the nightmarish public housing projects, the people who had the worst school system and were most often degraded by the Police Department, the people who received the fewest campaign promises and who were ignored as part of the campaign trail, had given him his third term. They had done it quietly, asking for nothing in return. Exactly what they got.

To regain white confidence, Daley turned his back on open housing and other integrationist measures that the national Democratic Party was slowly embracing. He stymied the civil rights movement, outmanoeuvring Martin Luther King and his Chicago press advisor, a young Don Rose, with unenforceable written promises that he never kept to improve conditions for black people. Boss Dawson died in 1970 and, with him, the guarantee of black votes for the Daley Machine. On 6 April 1971, Chicago elected Daley to his fifth term with most white voters supporting him once again. Mike Royko recalled that, when reporters asked the mayor whether any of the presidential contenders”Ted Kennedy, George McGovern, Edmund Muskie and Hubert Humphrey, all of whom condemned his police state tactics of 1968 “ had telephoned to offer their congratulations. Daley smiled and said, “All of them did.”

* * * * * * *

When Obama arrived in Chicago in 1985, its politics were still adjusting to the vacuum left by Richard J. Daley’s death in office in 1976. Daley’s successors were two reform Democrats, the first a woman, Jane Byrne, and the second an African-American, Harold Washington. Byrne was not re-elected, because she broke her promise to reform the patronage Machine she inherited from Daley and antagonised the city’s black population. Washington tried to dismantle the Machine, but the white old guard in the city council blocked him. Racial tension between the mayor and his leading opponent, Alderman Ed Vrdolyak, were so bitter that Chicago earned another of its disparaging nicknames, Beirut-on-the-Lake.

Twenty-three years old, somewhat naïf, Barack Hussein Obama organized church and neighbourhood groups to force the city to remove asbestos and lead paint from public housing. He also led a campaign for playgrounds in the ghetto. These were serious struggles that, as well as improving lives, taught ordinary people, whom he paints sympathetically in Dreams From My Father, that they could confront power and win. Maybe not the game, but a few points. By his own admission, Obama’s achievements as community organizer were few. One of his staunchest supporters, a woman he called Sadie in his memoir, told him, “Ain”t nothin” gonna change, Mr. Obama. We just gonna concentrate on saving our money so we can move outta here as fast as we can.”

In 1987, Harold Washington, who had at least listened to the poor community of the South Side, died in office. His successors were, like him, Democrats. The first was the city council’s temporary president, Eugene Sawyer, who was appointed to finish Washington’s unexpired term. An African-American whom many black voters saw as being too close to the white establishment, Sawyer lost in the 1989 Democratic primary to Richard M. Daley. The Daley Restoration rode in on the back of a disillusioned black electorate, who mostly stayed home from the polls.

In the meantime, Obama had left to study law at Harvard in 1988. While he was away, the Machine under the new Daley adapted to modern requirements. Daley Junior imitated his father by giving what patronage jobs he could, circumventing court rulings against the practice by hiring loyalists on temporary contracts; but he shifted the balance towards exchanging government contracts for funds to finance his campaigns. Media ads became more important than ward heelers. Contracts to build highways and collect rubbish replaced city jobs as rewards to a new generation with higher social aspirations than their union member fathers. The goldmine would be redeveloping the failed public housing projects, among America’s largest, that Daley Senior had built to confine the black population to high-rise blocks. The constant from Daley to Daley was public money for private profit.

Chicago’s poor had lost the hope of the Harold Washington years by the time Obama returned from Harvard in 1991, with, as he wrote, “the neighborhoods shabbier, the children edgier and less restrained, more middle class families heading out to the suburbs, the jails bursting with glowering youth, my brothers without prospects.” Obama, though, had prospects and did not return to community organizing. At first, he worked with Project Vote that registered 150,000 African Americans who helped Carol Moseley Braun to defeat two white males in the Democratic primary for U.S. Senate and go on to become Illinois” first black U.S. senator.

The law firm Davis, Miner, Barnhill and Galland hired Obama to work on civil rights and urban development cases. Its senior partners were Allison Davis, who left to become a property developer, and Judson Miner, whom Don Rose called “liberal, honest, progressive.”

Obama met and married Michelle Robinson, another Harvard lawyer, whose father had been a Daley precinct captain and patronage city worker. She went to work as an assistant to Daley’s chief of staff, under deputy chief Valerie Jarrett. Larry Bennett, who teaches Chicago politics at De Paul University, told me, “It’s a one-party city, and Obama has made his way in that system.” While maintaining that Obama was not a product of the Dailey Machine, Bennett observed, “Obama has one foot with the regular Democratic Party and one foot with the oppositional Democrats.” Whether he was seeking higher office or rights for the “grass roots,” Obama needed the Machine more than it needed him.

Ben Joravsky wrote of Obama in the liberal Chicago Reader,

When he returned in the early 90s, just out of law school, he was bright, young and incredibly ambitious, and the first thing he learned “ the first thing any ambitious wannabe politician learns around here”is that there’s no future in Chicago for anyone who defies Mayor Daley… For Obama, kissing the mayor’s ring is like putting that flag on his lapel. It’s part of the game he’s had to play to get elected.

Obama devoted 162 pages of his 442-page Dreams From My Father to his three years as a community organizer in Chicago. In the sequel, The Audacity of Hope, his subsequent political career received such little attention that New Yorker writer Ryan Lizza commented that “his life in Chicago from 1991 until his victorious Senate campaign is something of a lacuna in his autobiography.” This may have been because he was learning more from the legacy of Mayor Richard J. Daley than he had from Saul Alinsky. The first thing a Chicago politician learns is how to raise money.

* * * * * * *

Making money from nothing has been the Chicago way since its founding in the late 18th century as a trading post by John Baptiste Point DuSable, a freed Haitian slave. (“Chicago” derives from the Algonquin Indian word for “onion patch,” chigagou.) The Chicago method was best described by George Horace Lorimer in his “Letters from a Self-Made Merchant to His Son” in the Saturday Evening Post in 1901 and 1902:

Does it pay to feed in pork trimmings are five cents a pound at the hopper and draw out nice, cunning, little “country” sausages at twenty cents a pound at the other end? … You bet it pays.

Putting a few thousand dollars into a politician also paid, when the politician regurgitated contracts worth millions. One of the luminaries of the system in the late twentieth century was a Syrian immigrant named Antoin “Tony” Rezko. Born in Aleppo to a family of Syriac Christians in 1955, Rezko was nineteen when he reached the United States. He learned English and studied engineering at the Illinois Institute of Technology. He borrowed money to buy vacant lots in Chicago’s South Side and build cheap houses. His next ventures involved buying franchises to open fast food outlets for Panda Express Chinese fast food and then Papa John’s Pizzerias. His food empire expanded from Chicago’s South Side to Michigan and Indiana. The Chicago Tribune wrote in 2006, “Rezko pragmatically courted local politicians, such as befriending the aldermen who controlled zoning and land use decisions.” Rezko, his associates and his family gave generously to city and state politicians, at least $385,000 in ten years, and raised millions more.

In 1989, Rezko and his friend Charles Mahru established Rezmar Corporation to rehabilitate sub-standard properties with government funds and manage them on government contracts. They restored 1,025 apartments in thirty buildings at taxpayer expense. In 1990, one of the company vice-presidents, David Brint, read in the newspapers that a young man from Chicago had been named the first African-American president of the Harvard Law Review. Brint called Barack Obama and arranged for him to meet Rezko, who offered him a job. Although Obama declined, a friendship was born that would help to finance Obama’s first run for the state senate in 1996.

Don Rose put a benign interpretation on Obama’s involvement with Rezko. “He meets Rezko under innocent circumstances,” Rose said. “Rezko is doing the right thing. Lots of community groups with housing take up with developers.” Obama’s employer, Judson Miner, represented some of the Rezko projects. “Jud assigned Obama to handle some of the Woodlawn [Preservation and Investment Corporation] file.” Allison David had left the law firm she headed with Judson Miner to found Woodlawn, which went into partnership with Tony Rezko to convert a disused nursing home into an apartment building. Rose said, “Rezko was doing the right thing to build houses for the poor, but he was using some of the project as a personal piggy bank.”

As a leading donor and fund-raiser for political campaigns, Rezko bankrolled Richard M. Daley for mayor, Rahm Emmanuel for Congress, Rod Blagojevich for governor and the young Barack Obama. Rose admitted that Rezko’s largesse may not have been merely good citizenship. His businesses”property development and fast food franchises”needed “many and quick authorizations,” as well as subsidies, from government.

Valerie Jarrett, who hired Michelle Obama to work on Mayor Richard J. Daley’s staff, told the Boston Globe, “Government is just not as good at owning as the private sector because the incentives are not there.” Jarrett at the time was chief executive officer of Habitat, which managed more than 23,000 flats. She was one of six developers, along with Rezko, who gave at least $175,000 to Obama’s campaigns. (She now, along with Rahm Emmanuel, Valerie Jarrett and Daley’s former election strategist, David Axelrod, works in the Obama White House.)

Quick quiz: which of these do you believe?

(1) Public-private finance packages are a genuinely more efficient way of providing housing for the poor.

(2) Public-private finance packages are a sure way for politicians to repay those who financed their campaigns.

Hint: Tim Novak wrote in the Chicago Sun Times, “For more than five weeks during the brutal winter of 1997, tenants shivered without heat in a government-subsidized apartment building on Chicago’s South Side. It was just four short years after the landlords “ Antoin “Tony” Rezko and his partner Daniel Mahru”had rehabbed the 31-unit building with a loan from Chicago taxpayers.” Novak added that seventeen other Rezko buildings had been foreclosed by mortgagees and another six boarded up, leaving many of its former inhabitants homeless.

Chicago Tribune columnist John Kass, who has succeeded Mike Royko as bane of the Machine, wrote, “Obama hasn”t dared challenge Illinois Democrats on corruption.” The fact that Obama did not challenge Chicago’s bribery and chicanery does not mean he took part in it. Obama said repeatedly that Rezko received no favours from him. That assertion was contradicted by the discovery of a letter he wrote to the Department of Housing in 1998.

![]()

State and city treasuries advanced Rezko more than $14 million for the project, from which he and his project partner, Allison Davis, took development fees amounting to $855,00.

“In the state legislature,” political scientist Larry Bennett said, “Obama maintained a progressive tack on certain issues, but maintained relations with Daley.” Obama was more than a Machine functionary during his tenure in the state capital, Springfield. He taught at the University of Chicago Law School and sponsored reform of the state’s criminal justice system. Rob Warden, executive director of the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University School of Law, praised Obama’s civil liberties credentials. While Daley for more than two decades, first as the county’s top prosecutor, then as mayor, turned a blind eye to police torture that sent innocent men to death row, Obama pushed legislation to make it more difficult. “Barack engineered a law through the legislature that requires the police to record the entire interrogation,” Warden, who helped to draft the legislation, told me. Despite police resistance, Illinois became the first state to enact this defendant protection. Chicago police now video-tape all interrogations to prove they no longer torture suspects. “I don”t know how he twisted arms,” Warden said, “but he did.”

In 2000, Obama ran for Congress in the Democratic primary against the popular incumbent, Bobby Rush. While picking up an endorsement from the Chicago Tribune and liberal white votes in his home area around Hyde Park, Obama lost most of the African-American vote to the former Black Panther. It was said at the time that Daley gave his tacit support to Obama to send him to Washington rather than have to run against him for mayor one day. But Obama lost by thirty-one points, his first defeat.

That did not stop his bid two years later for the U.S. Senate. “When I decided to run for the U.S. Senate, my media consultant, David Axelrod, had to sit me down to explain the facts of life.” One fact was that he would need $5 million for the primary and another $10 to $15 million for the general election in November. “Absent great personal wealth, there is basically one way of raising the kind of money involved in a U.S. Senate race. You have to ask rich people for it.” The money came in, but it exacted a price. “I found myself spending time with people of means”law firm partners and investment bankers, hedge fund managers and venture capitalists.” He found that these people, many of them from backgrounds he would have come across at Columbia and Harvard Law School, “reflected, almost uniformly, the perspective of their class: the top 1 percent or so of the income scale that can afford to write a $2,000 check to a political candidate.” He is unusually frank for an American politician about the one per cent’s effect on him:

And although my own worldview and theirs corresponded in many ways”I had gone to the same schools, after all, had read the same books, and worried about my kids in many of the same ways”I found myself avoiding certain topics during conversations with them, papering over possible differences, anticipating their expectations.

In the same passage, he defended himself against the charge of selling out for money.

On core issues I was candid; I had no problem telling well-heeled supporters that the tax cuts they”d received from George Bush should be reversed. Whenever I could, I would try to share with them some of the perspectives I was hearing from other portions of the electorate: the legitimate role of faith in politics, say, or the deep cultural meaning of guns in rural parts of the state.

Of all the issues confronting America’s ruling class with, faith in politics and the Second Amendment right to bear arms are probably the least challenging. Nowhere in The Audacity of Hope did he claim to have vexed his benefactors with the message that their unearned wealth should be redistributed to create a more viable economy and more just society. Nor did he claim to have told them that government defence contracts should be cut back or that the banks and hedge funds should be more rigorously regulated. Again, he is frank with his readers, whom he would soon ask to vote for him:

Still, I know that as a consequence of my fund-raising I became more like the wealthy donors I met, in the very particular sense that I spent more and more of my time above the fray, outside the world of immediate hunger, disappointment, fear, irrationality, and frequent hardship of the other 99 percent of the population”that is, the people that I”d entered public life to serve.

His remedy was not to introduce legislation to separate electoral campaigns from big money. It was to dilute money’s influence with the participation of campaign volunteers on the basis that “organized people can be just as important as cash…”

Not many people have time for full-time, unpaid campaigning, he wrote,

[Y]ou go where people are already organized. For Democrats, this means the unions, the environmental groups, and the prochoice groups. For Republicans, it means the religious right, local chambers of commerce, the NRA [National Rifle Association], and the anti-tax organizations.

He won the Senate seat through a combination of sound politicking, money and luck (his opponent was caught up in an unfortunate sex scandal). Next, he found a house in the Kenwood neighbourhood near the University of Chicago that, with a cellar for 1,000 bottles of wine, was more suitable for a US. Senator to entertain his new friends than the condominium he shared with his wife and two daughters in Hyde Park. The deal he made to buy it was, by his own confession, “bone-headed.” Even Don Rose, despite his support for Obama, said the deal “didn”t pass the sniff test.” For help in

purchasing the property at 5046 South Greenwood, for which the vendor was asking $1.95 million, he went to his old friend and backer Tony Rezko.

Rezko had been an effective member of Obama’s senate campaign finance committee, along with fellow developers Valerie Jarrett and Allison Davis. By 2005, however, Chicago newspapers had already reported that Tony Rezko was under federal investigation for bribery, fraud and money laundering. The house Obama wanted was on one of two lots that belonged to a doctor, who was selling the two properties together. Obama and Rezko’s wife, Rita, completed purchase of the adjoining properties on the same day”Obama for $300,000 less than the sale price, Rita Rezko for the full price. Afterwards, Mutual Bank, which financed Mrs. Rezko with a loan of the legal maximum 80 per cent of purchase price, dismissed an employee, Kenneth J. Conner. Conner, who had accused the bank of overvaluing the vacant property at $650,000 to lend Mrs. Rezko the $500,000 she needed, told journalists, “The entire deal amounted to a payoff from Tony Rezko to Barack Obama.” Obama later bought a strip of land beside his property from Mrs. Rezko for $104,500. When the arrangements became public, Obama answered questions by the Chicago Tribune‘s editorial staff in March 2008. Had Rezko asked for anything in return from the prospective president? “No,” Obama said. “Because I had known him for a long time, and so I would have assumed I would have seen a pattern [of Rezko asking for favours] over the course of fifteen years.” Apparently, the letter he wrote on behalf of Rezko’s Cottage Grove scheme in 1998 did not count as a favour.

Federal prosecutor Patrick Fitzgerald, who has become to Chicago’s politicians what Elliot Ness was to Al Capone during Prohibition, won a conviction in June 2008 of Rezko on sixteen of twenty-four charges of corruption. He followed this up with the impeachment of Governor Rod Blagojevich for fraud, extortion and seeking to sell Obama’s vacant Senate seat to the highest bidder. Obama’s ties to Blagojevich were not close, but they were connected through the Cook County Democratic Party and common advisors like Rahm Emmanuel and David Axelrod.

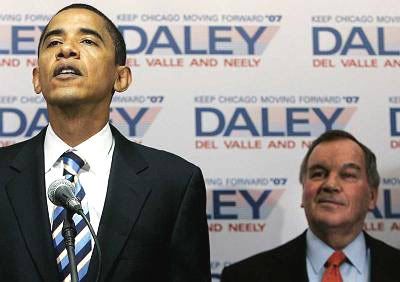

Obama never made an issue of the Daley Machine. As a politician, he did not join the South Side residents whose lives he once hoped to improve as an organizer in opposing the mayor’s excesses. Yet he kept what he called a “cordial, not close” relationship with the mayor. However, when he announced his candidacy for president in 2007, he endorsed Daley for mayor and Daley backed him for president. (That was the day Hillary Clinton should have known her campaign was over.) “It was a marriage of convenience, brilliantly brokered by David Axelrod, a campaign strategist for both men,” wrote Ben Joravsky in The American Prospect.

Obama’s endorsement cut the ground out from under Dorothy Brown, Daley’s most significant black challenger. And with Daley’s blessing it was suddenly safe for everyone and anyone in town to join Obama’s campaign for change and become a reformer. So long as it was Washington, and not Chicago, getting reformed.

Obama, who had learned about fund raising from the Chicago experts, went national in his search for money. His campaign used the internet to obtain small donations that involved ordinary voters in his fate, but it also did what the experts thought impossible: it raised more money from corporate American than the Clintons. The Center for Responsive Politics reported that among his biggest donors were Goldman Sachs at $955,223, JP Morgan Chase at $642,958, Citigroup at $633,418 and the largest corporate law firms, who are also registered lobbyists. His record-breaking $700 million in donations has set a new level for campaign funding, making high office more expensive than ever. It will inevitably leave elected politicians with more debts that some of their donors expect to be repaid.

* * * * * * *

There are two ways of doing politics short of revolution. One is for a community to seek participation in the system, as the once-disenfranchised peoples of South Africa, Bolivia and Brazil did. They put forward leaders to articulate their demands and, if necessary, take office for their benefit. The other way is for a politician to organise people to promote him for office and to support his demands. The first is a popular model, the second populist. George Packer wrote in the New Yorker, “Obama’s movement did not exist before his candidacy; its purpose was to get him elected.” He added that the “Obama movement remains something less than a durable social force.” Unlike the Democratic Party Machine in Chicago.

It would be a mistake to assume that Obama is owned by those who helped him to power anymore than Richard J. Daley was when he became mayor of Chicago in 1955. Mike Royko wrote of a cartoon that appeared in his newspaper, the Chicago Tribune, just after Daley’s election. He saw it in the house of Daley’s old friend, Alderman Tom Keane.

The cartoon portrays Daley as a grinning wind-up doll, clutching a sign that says “Give Chicago leadership.” Holding the oversized doll-crank are caricatures of John D”Arco, the Syndicate’s political representative, William Dawson, the black boss, Joe Gill, the party ancient, Artie Elrod, the Twenty-fourth Ward boss, Paddy Bauler, a boisterous ward boss and saloon keeper, and Keane himself, all smiling evilly.”

Keane told Royko, “Every time Daley comes over here, he looks at that thing and laughs.” Obama too may laugh one day at those who believe Richard M. Daley, David Axelrod, Rahm Emmanuel, Valerie Jarrett and the rest of the Cook County Machine will manipulate him. Yet, like Daley, he may know which favours must be repaid.

When Obama left Chicago for the White House this year, the city was much as he found it when he began his political life there in 1991. The Daley Machine was intact, favours were granted to cronies and the key to power remained the raising and dispensing of money. Obama will be only fifty-six years when he leaves the White House, provided the electorate grants him a second term in 2012. If he doesn”t disgrace himself, or perhaps if he does, he may yet become mayor of Chicago. He would be only three years older than Richard J. Daley was in 1955, and Daley lasted another twenty-one years.