October 11, 2023

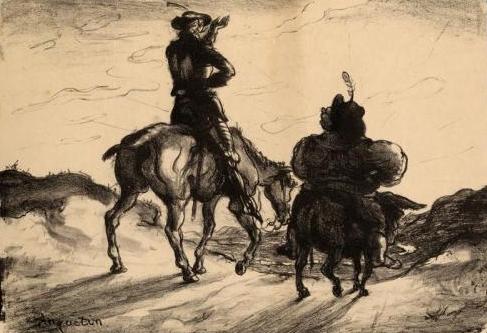

Don Quixote And Sancho Panza by Louis Aquetin

In Michael Lewis’ new biography of Sam Bankman-Fried, Going Infinite, Lewis quotes the accused cryptocurrency embezzler’s rationalist case against Shakespeare:

I could go on and on about the failings of Shakespeare…but really I shouldn’t need to: the Bayesian priors are pretty damning. About half the people born since 1600 have been born in the past 100 years, but it gets much worse than that. When Shakespeare wrote, almost all Europeans were busy farming, and very few people attended university; few people were even literate—probably as low as ten million people. By contrast there are now upwards of a billion literate people in the Western sphere. What are the odds that the greatest writer would have been born in 1564? The Bayesian priors aren’t very favorable.

Bankman-Fried’s assumption that talent should be proportional to population size is hardly a novel one. For example, in 1964 physicist John H. Fremlin published an influential article about the long-term consequences of unchecked population growth. Fremlin imagined a world covered in 2,000-story buildings. On the bright side, he noted:

One could expect some ten million Shakespeares and rather more Beatles to be alive at any one time, that a good range of television entertainment should be available.

Similarly, feminist novelist Virginia Woolf made a popular argument 94 years ago that the lack of a female Shakespeare proves how oppressed women were:

Let me imagine, since facts are so hard to come by, what would have happened had Shakespeare had a wonderfully gifted sister, called Judith, let us say.

Woolf surmises that Shakespeare’s equally talented sister, Judith, would have killed herself in despair. The 20th-century writer went on to imply that because women make up half the population but less than half the historic literary geniuses, that proves there must be oppressed women of comparable talent:

When, however, one reads of a witch being ducked, of a woman possessed by devils, of a wise woman selling herbs, or even of a very remarkable man who had a mother, then I think we are on the track of a lost novelist, a suppressed poet, of some mute and inglorious Jane Austen, some Emily Bronte who dashed her brains out on the moor or mopped and mowed about the highways crazed with the torture that her gift had put her to.

Indeed, to this day, the most famous playwrights tend to be male. One reason for this is that at least since the Broadway strike of 1919, writers for the stage are vested with property rights allowing them to dictate conditions to anyone mounting their work that writers for the screen can only dream about. One of Hollywood’s oldest jokes is about the blonde starlet who was so dumb she slept with the writer. But, you’ll note, Marilyn Monroe married playwright Arthur Miller.

Woolf was echoing a famous line in Thomas Gray’s poem “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” about the inevitability that only some fraction of all potential talent ever got a chance to flourish, if only because of early death:

Some mute inglorious Milton here may rest

Pundit Richard Hanania, whose book The Origins of Woke I reviewed here recently, then weighed in with “Shakespeare is Fake: When we have objective measures, the past is never better.”

As I mentioned in my review, while I admire his intellect, “Richard needs to watch his ego.” And now we see him declaring:

…I could copy Shakespeare’s style and produce something just as appealing….

To prove it, Hanania emitted what he assumed was a Shakespeare-like rhyming doggerel, not realizing that Shakespeare’s greatest works are written in unrhymed iambic pentameter:

Man so powerful yet so weak. Conqueror of stars yet farts and squeaks. Oh man! An ape we know it is true. Darwin has revealed me and you. Yet we go on, forward still. For if not us, then who will?

To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury

Signifying nothing.

Hanania gets on more solid ground by pointing to sports, where objective performances keep getting better. For example, over the weekend, the latest skinny Kenyan, Kelvin Kiptum, set a new world record in the marathon at two hours, zero minutes, and 35 seconds.

Still, not every sport is improving. Few would argue that American boxing is still as strong as it was in the middle of the 20th century when it was immensely popular. There has been an exodus of talent to other sports. For example, Ken Norton Sr. fought Muhammad Ali three times in the 1970s, winning once and losing twice, all on close decisions. Ken Norton Jr., a similarly impressive individual, played linebacker on three straight winning Super Bowl teams in the 1990s.

Women’s running records at 100m, 200m, 400m, and 800m are all from the 1980s when steroid tests were easy to fool.

Weirdly, horse racing, a sport with vast sums spent on eugenic breeding, isn’t getting all that much faster. The record for each of the three Triple Crown races (Kentucky Derby, Preakness, and Belmont) was set by Secretariat fifty years ago.

In many sports, however, there are no stopwatches to allow comparisons across eras. And because conditions keep improving (for example, running times are currently falling due to the introduction of running shoes with carbon fiber plates in 2019), subjective judgments about who was the best are still required. High school boys today run faster than Jesse Owens did in the 1930s, but that doesn’t mean they are greater in a nontrivial sense.

So, I’ve made up a list of the current consensus Greatest of All Time front-runners in various sports and when they flourished. I’m trying to be as uncontroversial as possible in these selections. You may have strong arguments about why, say, Michael Jordan wasn’t the best basketball player ever, but it’s reasonable to say the consensus is that the burden of proof should be on you.

Note that these choices are weighted toward career value over peak value. For example, slugger-pitcher Shohei Ohtani’s last three seasons have been unique in baseball history, but that isn’t long enough to contend for Greatest of All Time. The recent style of baseball seems to put unprecedented strains on the body (see the last few seasons of Mike Trout, Jacob deGrom, or Stephen Strasburg), so it’s less clear than ever who will enjoy two decades of reasonable health like Babe Ruth or Willie Mays did:

Basketball: Michael Jordan, 1980s–1990s

American Football: Tom Brady, 2000s–2010s

Ice Hockey: Wayne Gretzky, 1980s

Baseball: Babe Ruth, 1910s–1930s, or Willie Mays, 1950s–1960s

Cricket: Don Bradman, 1920s–1940s

Golf: Jack Nicklaus, 1960s–1970s, or Tiger Woods, 2000s

Tennis: Roger Federer, 2000s, Rafael Nadal, 2000s–2010s, or Novak Djokovic, 2010s–2020s

Soccer: Pele, 1960s, Diego Maradona, 1980s, or Lionel Messi, 2010s

Horse Racing: Secretariat, 1973

Boxing: Sugar Ray Robinson, 1940s, or Muhammad Ali, 1960s

Sprinting: Usain Bolt, 2010s

Swimming: Michael Phelps, 2000s–2010s

Greco-Roman Wrestling: Aleksandr Karelin, 1990s

I could go on, but that’s a reasonable sample size. Out of these twenty contenders—nineteen of them human—only three (Ruth, Bradman, and Robinson) are from the first half of the 20th century, and eight peaked in this century. So, even using subjective opinions, it’s clear that well-informed sports fans find that athletes have generally been getting better at achieving greatness.

One reason is because modern athletes can afford to play longer. For instance, Olympic sports used to insist upon amateurism, so Jim Thorpe had his gold medals taken away for playing minor league baseball for pay, while Michael Phelps went to five Olympics because he could make a good living for being a gold medalist.

And even pros usually had to have an off-season job. Ruth was able to extend his dominance through his 30s because he was one of the few athletes in the world at the time who was paid enough to hire a personal trainer and work out all winter. (When an early-1930s sportswriter asked why he was paid more than the president, Ruth replied, “I had a better year than Hoover.”)

What about non-sports fields?

Is fame all just who you know?

For example, consider the links between four of the most famous individuals in history: Socrates taught Plato who taught Aristotle who taught Alexander the Great.

Maybe they weren’t so great and they were just drafting off each other’s renown?

Then again, Alexander succeeded at a world-historical level in the extremely competitive field of conquering. And his tutor Aristotle had important things to say about numerous subjects. And have you read any of Plato’s dialogues? For example, in the early pages of The Republic, Plato touches ever so briefly upon economics, yet suggests that he grasped Adam Smith’s theory of the division of labor and perhaps, astonishingly, David Ricardo’s famously nontrivial theory of comparative advantage.

Seriously, though, it’s not impossible that Socrates’ reputation is inflated by the fact that Plato, a definite genius, starred him in his dialogues. After all, we don’t have any text written by Socrates. Socrates also appears in works by his contemporaries Xenophon and Aristophanes, suggesting he was a memorable figure, but without appearing to be one of the greatest philosophers of all time.

Still, the most straightforward explanation is that Athens 2,400 years ago, like London 425 years ago, was one of those rare times and places when the future opens up.

Why? Lots of people have had lots of opinions. For example, in Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye, a drunken client suddenly informs detective Philip Marlowe that cultural progress is due to gays:

“The queer is the artistic arbiter of our age, chum.”…

“That so? Always been around, hasn’t he?”…

“Sure, thousands of years. And especially in all the great ages of art. Athens, Rome, the Renaissance, the Elizabethan Age, the Romantic Movement in France—loaded with them.”

I dunno if that’s true, but the point is that many people have been trying to figure out for many years why certain spots and moments are more important than others.

For example, Jann Wenner, who in 1967 founded Rolling Stone magazine to write about the new electric guitar music of the 1960s, was recently canceled from his post at the head of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame because he was unapologetic that he published a book of his interviews with his seven favorite rock musicians and they all turned out to be white men, six of them born in the 1940s. In truth, it was simply easier to pick up an electric guitar in 1965–1971 and do something historically great in rock music than it was fifty-plus years later when it’d all been done before.

For instance, Shakespeare was clearly the right man at the right place at the right time. The London stage had only become a professional institution about fifteen or thirty years before his arrival. This lag provided Shakespeare with enough time to enter into a mature profession, but also without too much weight of history bearing down upon him.

Note that while Will Shakespeare composed an average of a couple of plays per year, Tom Stoppard has composed barely half as many plays in a career more than twice as long. Stoppard says that while it takes him one year to write a play, he can only come up with an idea worthy of a play every three or four years.

It’s not that Stoppard, an extremely energetic man, is lazy. For example, over about a decade and a half in the 1980s and 1990s, he had a hand in script-doctoring virtually every Steven Spielberg movie. It’s just that in Stoppard’s time, in contrast to Shakespeare’s time, centuries of literary creativity bear down upon the author.

For instance, Stoppard’s greatest play, 1993’s Arcadia, is a knockoff of A.S. Byatt’s 1990 novel Possession about small-souled 20th-century English Lit academics trying to research large-souled 19th-century Romantic geniuses. But most of Stoppard’s plays aren’t quite as obviously awesome as Arcadia, so he felt more impelled to come up with original ideas for them. In contrast, it’s hard to imagine Shakespeare caring about plot originality.

One of the funnier explications of how cultural history bears down upon modern artists is Jorge Luis Borges’ famous comic short story “Pierre Menard, Author of The Quixote.” Menard is a fictional early-20th-century French symbolist poet of the highest aesthetic ambition who devotes his life to writing two of the 126 chapters of Cervantes’ Don Quixote, which more or less invented the novel 300 years before.

Menard’s self-imposed rule is that while he can initially rewrite Don Quixote anyway he likes, he must eventually get around to crossing out his own lines and, as an authentic 20th-century artist, “sacrifice these variations to the ‘original’ text and reason out this annihilation in an irrefutable manner.”

Not surprisingly, Menard is only 2 percent as productive as Cervantes, but his word-for-word rendition is, in the words of the critic, “almost infinitely richer” because:

To compose the ‘Quixote’ at the beginning of the seventeenth century was a reasonable undertaking, necessary and perhaps even unavoidable; at the beginning of the twentieth, it is almost impossible. It is not in vain that three hundred years have gone by, filled with exceedingly complex events. Amongst them, to mention only one, is the ‘Quixote’ itself.”

Borges expounds:

It is no less astounding to consider isolated chapters. For example, let us examine Chapter XXXVIII of the first part, “which treats of the curious discourse of Don Quixote on arms and letters.” It is well known that Don Quixote…decided the debate against letters and in favor of arms. Cervantes was a former soldier: his verdict is understandable. But that Pierre Menard’s Don Quixote—a contemporary of ‘La Trahison des Clercs’ and Bertrand Russell—should fall prey to such nebulous sophistries!

The narrator attributes the new Don Quixote’s post–Great War endorsement of combat to “the influence of Nietzsche.”

Like an electric guitarist in the late 1960s, the contemporaries Cervantes and Shakespeare partook of what Harold Bloom called the “intoxication of unprecedentedness.”