April 12, 2023

Source: Bigstock

About thirty years ago I attended a presentation by an executive at a vast snack and beverage company. She announced that her firm’s goal was to have their delicious sugary and salty products within arm’s reach of every American at all times. Maybe they’d never quite fully succeed, but damn it, they were going to try.

“Uh-oh,” I said to myself. “The future is going to be fatter.”

And so it was.

America, with 42 percent of our population being obese as of 2017–2020, up from 31 percent at the turn of the century, is now the fattest country outside of some beefy Pacific islands. We’re even worse off than traditionally sedentary Muslim cultures like Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Turkey. But the rest of the Anglosphere isn’t too far behind us. Countries that I long associated in my mind with healthy outdoor exercise, such as Australia and New Zealand, are now tipping the scales too.

Not surprisingly, our overeating is hurting our lifespan, despite America’s vastly well-funded health care system pulling the occasional rabbit out of the hat. For example, I beat non-Hodgkin’s lymphatic cancer in 1997 with the help of a monoclonal antibody that didn’t exist in 1994. Heck, the concept of a monoclonal antibody was science fiction until shortly before I needed one.

Growing up in the 20th century, I took it for granted that Americans were the richest, tallest, and longest-lived. Well, we’re still pretty rich, but our life expectancy has taken a pounding.

For a while, America’s problem was mostly one of opportunity cost: Without our gluttony we could have been living longer, as shown by our European cousins, but at least our lives weren’t getting shorter.

But then in this century, major segments of the population started to die sooner on average as America’s bad habits drifted from chips to opioids. During an era obsessed with the demise of black delinquents such as Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown, virtually nobody noticed that the white working class was increasingly dying “deaths of despair”—suicide, opioid overdoses, and cirrhosis—until late 2015 when, fortuitously, Angus Deaton won the Nobel Prize for economics just before his landmark paper with his wife, Anne Case, came out.

This trend was particularly striking because nonwhite lifespans had been getting better in the early 2000s: Blacks weren’t shooting each other as much as during the early-1990s crack-war eras or dying of AIDS as often. After many marginal Mexicans went home when the Bush housing bubble burst, the “Hispanic paradox” of Latinos living longer than would be expected relative to their income, frequent lack of health insurance, and pudginess became even more apparent. And Asians, especially Asian women, continued to live longer and longer. Only American Indians, who share quite a bit in common with the Scots-Irish, suffered a similar fate.

But then came the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement with the Ferguson brouhaha in 2014. As cops got the message to not pull over nonwhites as much, traffic fatalities and shootings rose. Only a few noticed at the time that the Ferguson Effect applied both to murder and road crashes.

The Trump administration briefly cooled things off, but then came 2020 and a massive upsurge among the younger cohorts in what I call “deaths of exuberance”—homicides, motor vehicle accidents, and overdoses on recreational drugs—fueled by Covid stimulus and the racial reckoning’s depolicing. Reporter John-Burn Murdoch of the Financial Times reports:

More years of American lives were erased by drugs, guns & road deaths in 2021 alone than from Covid during the whole pandemic. The result is that the US is the only developed country where even if you strip out all Covid deaths, life expectancy still dropped by a year since 2019.

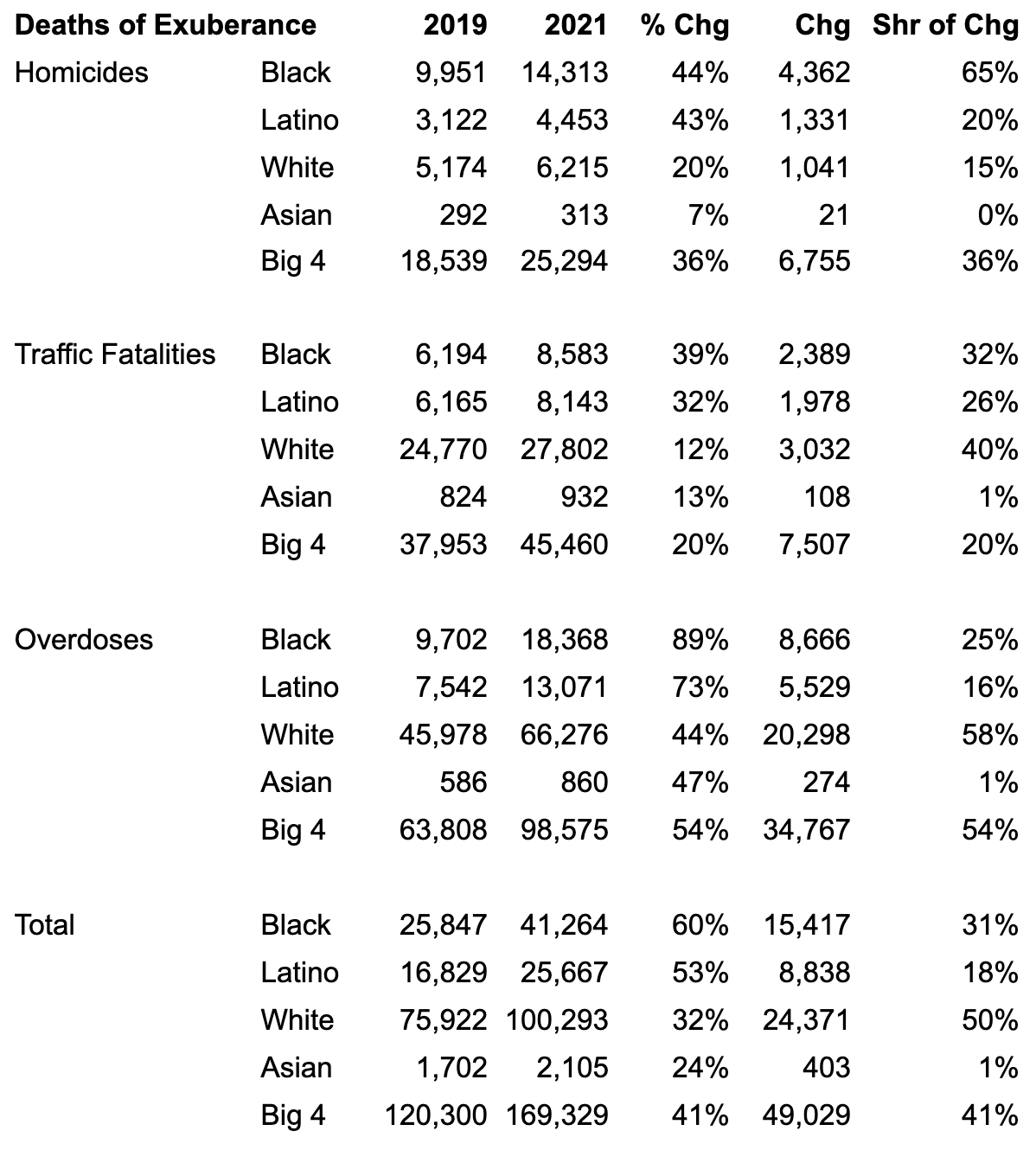

Ironically, but not surprisingly, with America’s leadership class shouting constantly about racism in 2020, the triumph of the Black Lives Matter mindset helped get far more blacks and Latinos killed in knuckleheaded fashions in 2021 than in 2019.

For example, deaths by homicide among blacks (almost all at the hands of other blacks) surged from 9,951 in 2019 to 14,313 in 2021, according to the CDC’s WONDER database. As the police refrained from pulling over bad drivers, African American motor vehicle accident deaths likewise surged from 6,194 to 8,583.

Death rates among Latinos, who had been something of a success story in this century, rose almost as much as among blacks.

Drug arrests are way down in this decade, but the consequent decline in shootings long promised by libertarian economists has yet to materialize.

The biggest death toll increase was due to overdoses. Black overdose deaths rose 89 percent from 2019 to 2021, Latinos 73 percent, whites 44 percent, and even Asians were up 47 percent.

Are overdoses still deaths of despair, as Case and Deaton labeled them back when they tended to be found most among middle-aged Rust Belt working-class whites who had first gotten hooked on oxycodone painkillers, then, when they lost their prescriptions, took up Mexican black tar heroin? Sam Quinones reported in his 2016 book Dreamland that the cartels avoided selling heroin in black inner cities because the black tendency toward gunplay attracted too much attention. In contrast, the cartels reasoned, nobody in the American media would much care if small-town whites in Kentucky were dropping dead.

But Quinones reported in his 2021 book The Least of Us that heroin had disappeared, replaced by more potent and cheaper synthetic fentanyl. The raw ingredients are made in China and secondary assembly done in Mexico. Since around 2015, the old self-restraint that kept Mexican heroin out of the inner city is long gone in the fentanyl era.

It’s unclear what fraction of fentanyl overdoses are “deaths of despair” among people wanting downers to make the pain go away versus “deaths of exuberance” from people looking to get high. Retail dealers have taken to lacing party drugs like cocaine and meth with fentanyl because users seem to like the effect. Some percentage of fentanyl overdoses are from poor quality control when mixing fentanyl into other drugs and accidentally giving users fatal overdoses.

Another lethal pattern is that addicts cycle through both meth and fentanyl to self-medicate for the other.

So, don’t do drugs. Especially now, during the fentanyl era.

A popular spin on this death data was found in The New York Times last week:

It’s Not ‘Deaths of Despair.’ It’s Deaths of Children.

By David Wallace-Wells

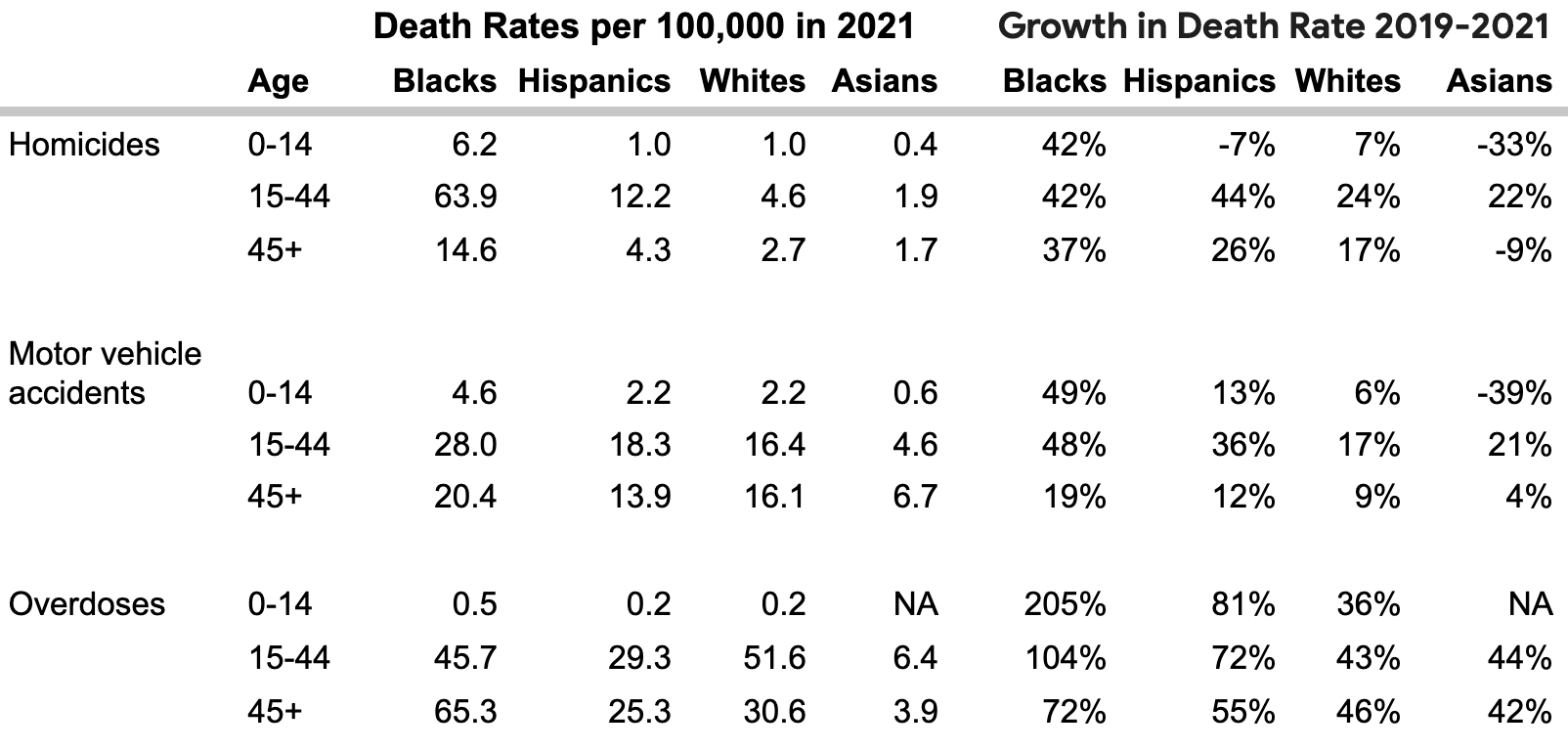

But much of the recent reporting on deaths of “children” is misleading due to counting as kids those up through age 19. Instead, I’ve broken the CDC data down into three groups: age 0–14, 15–44, and 45 and over. Among whites, Hispanics, and Asians, we are seeing most of the surges in deaths of exuberance among the 15–44 set, as you’d expect.

Among blacks, the situation is, as usual, somewhat more dire, with higher rates of collateral damage among children than in other races.

If you read the article all the way through, the next-to-last paragraph spills some beans about what’s really going on (as is common in The New York Times):

Most of the increase in pediatric mortality was among males, with female deaths making only a small jump. Almost two-thirds of the victims of homicide were non-Hispanic Black youths 10 to 19, who had a homicide rate six times as high as that of Hispanic children and teenagers, and more than 20 times as high as that of white children and teenagers. In recent years, the authors of the JAMA essay write, deaths from overdose were higher among white children and teenagers, but increases in the death rates among Black and Hispanic children and teenagers erased that gap, statistically speaking, in 2020.

Of course, what that all boils down to is that Black Lives Matter was a catastrophe for black (and brown) lives.

But how readers many get it?

Judging from the comments, a large number of New York Times subscribers concluded yet again from this article that Republican white men in MAGA hats with scary rifles are slaughtering the nonwhite children of America in vast numbers.

It’s remarkable how successful the prestige press has been over the past three years in obfuscating their own culpability in the Floyd Effect.

In his last paragraph, Wallace-Wells acts irate that Case & Deaton finally got some publicity for their deaths-of-despair findings in 2015, when in this decade it’s nonwhite “children” who are now dying in increased numbers due to the hazy abstractions of “inequality,” “violence,” and “social brutality,” which, no doubt, translate in the minds, such as they are, of Times subscribers as “evil white men”:

In this way, the new data manages to invert and upend the deaths of despair story while only confirming the country’s longstanding patterns of tragic inequality. That narrative, focused on the self-destruction of older and less-educated white men, took hold in part because it pointed to an intuitive sense of national psychic malaise and postindustrial decline. But the familiar narratives about the country’s problems are proving more enduring: The country is a violent place and is getting more violent, and the footfall of that violence and social brutality is not felt equally, however much attention is paid to the travails of the “forgotten” working class.

But not, of course, due to any choices made by nonwhites. That would be unthinkable.