February 23, 2022

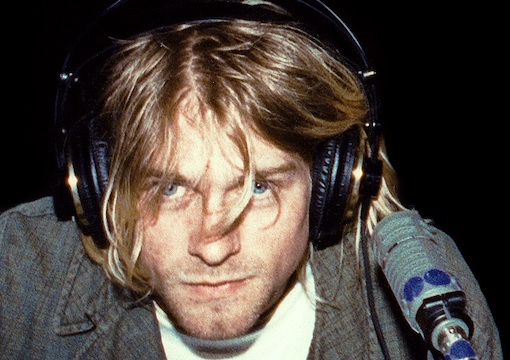

Kurt Cobain

Source: Julie Kramer

When it was suggested that I review the new nonfiction book The Nineties by Chuck Klosterman, I assumed he would be an ideal analyst of that distant decade because, after all, he’d written that very 1990s novel Fight Club, hadn’t he? But it turns out that was by Chuck Palahniuk, which shows you what an expert on the 1990s I am. Being fourteen years older than Klosterman, I can tell you a lot about 1976–1986. But the 1990s are a blur for me from too much having-a-life.

Klosterman, who was born on a farm in Minnesota, writes:

Transparency requires me to admit a few things here, if only to aid those primarily reading this book in order to locate its biases: I was born in 1972. I’m a white heterosexual cis male…. I am comfortable with my service as a demographic cliché.

Now that I’ve looked him up, I associate Klosterman with his frequent collaborator Bill Simmons, the revolutionary sports journalism impresario.

Simmons’ big insight was that old-time newspapers assumed that there is a shortage of information. Hence, sportswriters would laboriously follow the hometown baseball team around the country so they could go down to the locker room to ask the game’s hero what kind of pitch he knocked out of the park.

Simmons realized that there is now an abundance of information, so there is a role for a new type of meta-journalist to trawl through as much of it as possible to notice patterns and causal mechanisms.

Klosterman, a rock critic, sportswriter, and all-purpose white male Gen-X culture nerd of the type who flourished before social media made the internet too easy, is still at it in a world grown suspicious of guys who are bright and white. He’s intensely intelligent, insightful, and sensible, qualities that don’t always coincide. He offers numerous fairly abstract conclusions about Generation X, but always based on countless examples.

He can also be very funny. For example, from his chapter on the Clear Craze:

Why, from roughly 1992 to 1995, did the beverage industry operate from the position that there was an underserved sector of the populace who desperately wanted transparent drinks?

Suddenly, store shelves were laden with Crystal Pepsi and Tab Clear, a vile-tasting caffeine-free diet drink self-defeatingly sold only in opaque cans. Supposedly Coke used Tab Clear to torpedo the expensive launch of Crystal Pepsi by confusing consumers through stupidity-by-association:

The prospect of a terrible beverage created to kamikaze a moronic beverage is an apt metaphor for this entire period of marketing.

And then there was Zima:

A concept like Zima—a citrusy version of Coors beer, scrubbed into translucence by charcoal filters—was the liquid manifestation of a cultural phase in which informed insincerity was the only way to understand anything…. Every new Zima went down slightly worse than the previous Zima. There was, however, something perversely enticing about a drink that seemed to come from a post-apocalyptic wasteland in which color did not exist. There was an ingrained assumption that Zima must be expressly targeted at somebody, but nobody knew who that was…. Zima was ridiculous…but did that actually mean it was brilliant? The only viable conclusion was “sort of.”

On the other hand, in 2022, Zima is one of the few things you can make fun of with no fear of getting your career canceled. Much of The Nineties appears pitched at such a high intellectual level that it’s likely to slip past members of the volunteer auxiliary thought police looking for crimethinkers.

First, What Would Kurt Cobain Do? Would the Nirvana frontman tormented by his own popularity go around shouting, “Booyah 1990s!”? If Seattle was the spiritual home of the 1990s to smart young rock writers like Klosterman, it’s worth noting that the Pacific Northwest appears to be the least extroverted place in America: hence, the Seattle Freeze. The ’90s white Gen-X affectations of irony, aloofness, fear of selling out, etc. were a kind of revenge against the capitalist, globalist pop commercialism of the ’80s:

The concept of “selling out”—and the degree to which that notion altered the meaning and perception of almost everything—is the single most nineties aspect of the nineties. The complexity, nuance, and application of the term sellout was both ubiquitous and impossible to grasp. Nothing was more inadvertently detrimental to the Gen X psyche.

These values are, of course, the antithesis of hip-hop’s. In one 1998 episode of The Larry Sanders Show, Phil the Writer has penned a sitcom pilot about a Seattle grunge band. The network is excited and thinks it would be perfect for Dave Chappelle to star in. Dave tells Phil he loves it, but just lose the five white guys, lose Seattle, and make it about a DJ in Baltimore.

Second, in the music criticism field, “rockists” like Klosterman are being put out to pasture to make room for “poptimists” who go on about how Beyoncé’s new hairstyle is fierce. So, Klosterman isn’t in a hurry to be too clear about what’s on his mind.

Hence, he tends to alternate between Walter Benjamin-level intellectualization and concrete clarity:

In the same way that every historical era feels extraordinary within the moment it happens, the present-tense status of culture exists in a constant state of crisis, with the tenor of the crisis shaped by whatever people assume to be the cause. The assumption in the nineties was commercialism. The assumption this morning is capitalism.

The stereotypical 1990s cultural personality, such as Cobain, worried about corporate commercialism. So the solution was to form your own grunge band, fanzine, Usenet forum, or start-up.

In contrast, the characteristic concern of the 2020s is capitalism. Specifically, the worry that corporate capitalism cannot wholly resist the menace of blue-collar populism unless the workers (the marketing interns, human resources executives, diversity consultants, sensitivity readers, and the like) seize the means of production at the giant media companies and enforce corporate values with an iron fist on the customers and the talent (e.g., independent thinkers like Klosterman) alike.

Hence, Klosterman treads gingerly around even that central cultural event of the 1990s, O.J. Simpson:

The detail always noted in remembrances of the Bronco chase is the throngs of bystanders cheering for Simpson as the car rolled down the freeway, congregating on overpasses and holding makeshift cardboard signs proclaiming, “The Juice Is Loose.” It seemed perverse then and still seems perverse now. Yet this can also be understood as the primordial impulse of what would eventually drive the mechanism of social media: the desire of uninformed people to be involved with the news, broadcasting their support for a homicidal maniac not because they liked him, but because it was exhilarating to participate in an experience all of society was experiencing at once.

That’s very interesting. I wouldn’t have thought of it.

Yet, I would make the point that after the growing political correctness of the early 1990s, the O.J. case probably delayed our current Great Awokening for two decades by making clear to even the nicest white person that, contrary to what you might assume from the media, blacks aren’t always right.

The Nineties does contain one moment in which Klosterman drops the double masks of 1990s irony and submission to 2020s tyranny and takes pride in his generation compared with today’s youth:

The enforced ennui and alienation of Gen X had one social upside: Self-righteous outrage was not considered cool, in an era when coolness counted for almost everything. Solipsism was preferable to narcissism. The idea of policing morality or blaming strangers for the condition of one’s own existence was perceived as overbearing and uncouth. If you weren’t happy, the preferred stance was to simply shrug and accept that you were unhappy.