January 18, 2021

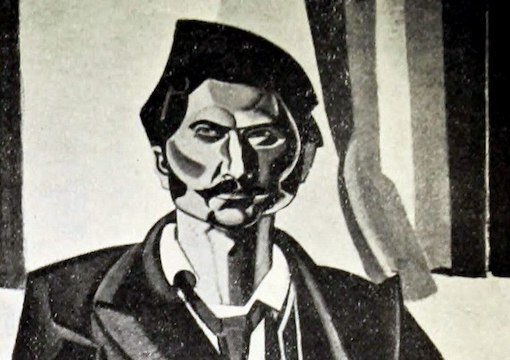

Ezra Pound by Wyndham Lewis

“My goal is to save the public soul by first punching it in the face.” —Ezra Pound

The main failure of the rise of the conservative right in America has been its fear of producing its own brand of cultural elitist in the style and substance of the well-bred Reactionary. Its cultural contribution has produced no aesthetic vision, no artistic sophistication—only the cult of commentary, endless commentary. There we stand after all this time: no film studios, no high-end literary publishing houses, no museum board of directors of consequence, not a single Ivy university under our influence, no “great editors” of the Buckley–Hilton Kramer or even Lewis Lapham–George Plimpton variety; no Condé Nast, no sitcom/dramas of interest save so many rather twee “aristocratic” nostalgia series lavish with bygone-era minutiae.

In short, our conservatism contains none of the cerebral heft and fervor possessed by the late, great 20th-century “Man of the Right” (his counterpart, the Albert Camus class of the “Man of the Left”). We are devoid of that generation’s intellectual anarchy; the art-obsessed, multilingual proto-Fascist who could create poignant works of abstract grandeur and literary grace that fused language and love of beauty with intransigent political views. Their class was one of spiritual courage and daring—and they would have had nothing to do with the right as it’s known today.

Ezra Pound, Wyndham Lewis, T.E. Hulme, W.B. Yeats, T.S. Eliot, Wallace Stevens, D.H Lawrence; the literary and art movements known as Futurism, Vorticism, and, to an extent, Expressionism… These monstres sacrés and their institutional expression raged from the margins of the general leftward drift of that totalitarian century and championed patriotism, nationalism, industry, and, via the traditionalist strain, monarchy. They regarded democracy with revulsion and saw in any kind of Mussolini-to-Franco range of dictator a prince-tyrant and future savior of that ever-flickering twilight known as “the West.” They were subversives desperate for authority, but of a heroic variety: classical, mystical, and unapologetically übermenschlich. “We wish to glorify war—the only health of the world,” wrote F.T. Marinetti, founder of the anarcho-industrial art movement known as Futurism, last showcased at a spectacular exhibit at the Guggenheim in 2014. “Militarism, patriotism, the destructive arm of the anarchist, the Beautiful Idea, the contempt for women…” This was the movement’s rallying cry and creed. But it produced masterpieces.

The poets, artists, publishers, and editors gathered around these diverse “right-wings” made up a formidable intellectual force. It was a mix that ranged in aesthetic ethos from Hulme, the “mercenary of modernism” and war veteran who famously fought Bertrand Russell on the battlefield of metaphysics, to T.S. Eliot writing his seminal “Tradition and Individual Talent” in 1919, to Yeats the romantic nationalist defending the “racial supremacists” of the Irish cause, to Wyndham Lewis declaring: “You as a Fascist stand for the small trader against the chain store; the nation against the super-State, the creator against the middleman….” To be sure, these artists had their reprehensible excesses. But it was from a weighty arsenal of intellectual artillery that they fired their shots into the vacuum of an apocalyptic and terrified age.

Their principal literary and art movements were known as Vorticism and Futurism, as referenced above. The latter, formed under the specter of World War I by such artists as Giacomo Balla, Umberto Boccioni, Gino Severini, and Tullio Crali, was a colorfully nihilistic descendant of Cubism and forerunner of one powerful strain of Expressionist painting and cinematography that exalted “the Machine,” the urban fortress and military combat in a style that was hard, geometric, violent, and utterly captivating. Vorticism, led by Pound and Lewis, was its London-born literary version that took root in “Ulster politics, labor unrest and the pending European conflagration,” while its short-lived flagship magazine, Blast, was the subject of respectful New York Times and Times of London feature coverage for its well-educated outlandishness and star writers.

Despite this unmoored mix of tradition, radicalism, Beauty-with-a-capital-B, war lust, anti-Statism, the small town, and the Industrial Age, “conservative” and “populist” this generation of the right decidedly was not. “My goal,” stated Pound famously, “is to save the public soul by first punching it in the face.” Yet it is in that decidedly populist statement that one finds the particular genius of this intellectual generation. For, in the name of Art, they were so far to the right they ultimately gathered at the outer banks of the left. That is to say, the tactics, the passion, the scholarship were as intensely energized a collective force as those of their totalitarian mirror opposites. Their ultimate contempt, just as that of their Socialist-Communist counterparts, was directed against the venerable “man on the street” and his slight superior, the suburban bourgeoisie. Given this shared contempt, the “suburban anti-Semite,” as Allen Ginsberg called his later-life friend Ezra Pound, regularly published the best left-wing writers in Blasta: The likes of Sydney Webb and Henri Bergson were featured alongside John Galsworthy, Benedetto Croce, and Lytton Strachey.

This mindset is what lent their Fascist or “Fascist” leanings a universally attractive bent. The objective of the Vorticist movement, a kind of right-wing Bloomsbury Group, was “to create a definitive force against amorphous thinking” whereby Pound tasked himself to become the prime mover of modern poetry, prompting the decidedly un-rightist Carl Sandburg to credit Pound for doing “the most of living men to incite new impulses to poetry.” Pound, for whom Mussolini was a kind of latter-day Sigismondo Malatesta, cuts a sympathetic figure because of his assistance to writers of all political hues. The power of art was placed before that of politics, and therefore “the right” resonated—deeply, emotionally, and so memorably. It was this aesthetically democratic mindset (of a group at times far more hostile to democracy than to that of any looming Red menace) that left that generation of right-wing intellectual a lasting, shadowy appeal, if not influence.

Such has been the main failure of conservatism in America—the lack of appeal to Imagination and of the ability to leave behind works of lasting emotional impact. In a word, it fails because it does not have the creative courage of the mad, bad highbrow right of generations past. It is all grassroots and no bloom.