August 17, 2019

Source: Bigstock

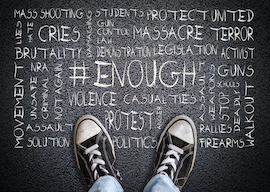

Is attention to the correct use of words mere pedantry or, as Confucius thought, the necessary foundation of a healthy state? I am with Confucius on this, which is why I was disturbed by President Trump’s words after the recent mass shooting in El Paso. They were exactly wrong.

The president called the perpetrator cowardly. This was wrong for two reasons. First, he was not cowardly, and second, bravery in the commission of such an act is not a virtue.

To take a gun and shoot people down in the knowledge that you will more than likely be killed yourself, or if not killed will face the grimmest of futures, is not cowardly and takes more courage than most of us have. Indeed, if such acts as this required no courage, they would probably be a great deal more frequent than they are.

Bravery does not by itself make an act better, because bravery in pursuit of an evil end is not a virtue but a multiplier of vice. A man who is prepared to die for an evil cause is worse (though he is braver) than one who is not. The latter may at least have reservations about the evil he has espoused. That bravery is not by itself a virtue was appreciated by so great a moral philosopher as Edgar Wallace, who wrote in The Four Just Men that “There are thousands of men who are physically heroes and morally poltroons….”

President Trump also said that there was no justification for killing innocent people such as the victims of the perpetrator. This again was quite wrong. It suggests that there might in everyday life be a group of people whom it would be right, or at least not so bad, to kill in this way, namely the guilty. Of what crime or conduct did President Trump consider the victims to be innocent that they should not be mown down more or less at random? All of us, after all, are guilty of something. It is even possible that some of the victims were not very nice people, but that is utterly beside the point (if you shoot enough people, some of them will be bad). The moral qualities of the victims, good or bad, were irrelevant to the reprehensibility of the act. It is no defense to murder that the victim was a miserly hermit whom no one will miss.

President Trump is not alone in his misuse of words, indeed it is almost standard for politicians to accuse terrorists of cowardice merely because their victims are usually unarmed, or at any rate taken by surprise. Even the extremely brave hijackers of the planes that flew into the World Trade Center were called cowardly. It is as if, once you have decided that someone is bad, any epithet will do to denounce him.

This doesn’t matter only if the effort to think clearly doesn’t matter, if all that counts in using language is to get some emotion, real or faked, off your chest, or publicly to demonstrate your virtue by comparison with someone else. But to write off terrorists as cowards is not only to misdescribe them but to underestimate them. It is a willful failure of understanding, a preference for comfort over truth.

In Britain, spokesmen for the police are particularly given to the Trumpian misuse of language. After some particularly gruesome crime, they are inclined to say, “This was a completely senseless murder,” or “This was a robbery that went tragically wrong.” Their words conjure up an ideal world in which all murders are sensible and all robberies go according to plan. Is it that the policemen do not fully understand the implications of what they say, or is it a symptom of their failure to understand the fundamental purpose of their work, which is manifest in many other ways?

Little misleading imprecisions in the use of language are frequent. In the days when I wrote quite often for a certain newspaper, I had reason to telephone it regularly, always through a central switchboard. Every time, for several years, that I did so, I heard the same recorded message: “Switchboard is very busy today, but your call will be answered as soon as possible…”—followed by a snatch of “Greensleeves” and an irritatingly intermittent repetition of the message.

The message was neither fully a lie nor fully a truth. Perhaps switchboard, through underinvestment, was very busy, but the addition of the word today implied, and was meant to imply, what was untrue, namely that there were days when it was not very busy by contrast with today. A person who called but once would assume that he had just been unlucky on the day he called.

What distressed me was my impotence in the face of this imposture. To whom could I protest? It was a tiny thing not worth bothering much about. But most of our life is composed of tiny things. Yesterday, for example, the butcher (in France) put my purchases in a bag that said “Your butcher is a professional—you can trust him.” Surrounding this reassuring message were happy gamboling lambs, smiling cows, and laughing pigs, as if all of them couldn’t wait to be turned into chops, fillets, mincemeat, etc.

In the political sphere, things are even worse. The word austerity in Europe, for example, is used to mean an attempt to approximate government expenditure to government income, or to reduce the rate of accumulation of debt. Whether to do so is a good idea or not is another question upon which I daresay economists will argue: Debt can be used to fund profitable investment or sumptuary expenditure, or to prop up a standard of living that is not fully earned. But whatever else approximating expenditure to income may be, it is not austerity, and to call it such is in effect to lie, or at the very least deliberately to create a misleading impression, that of a government of Scrooges. But an approximately balanced budget is no more austerity than is a terrorist or a mass gunman a coward.