November 20, 2014

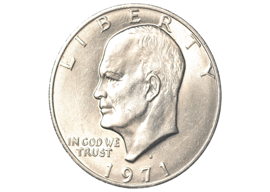

Source: Shutterstock

I have been reading Paul Johnson’s new short biography of Dwight Eisenhower. This fulfills a long-standing intention of the feebler kind”a velleity, Bill Buckley would have said. Thus:

In his 1983 book Modern Times, Paul Johnson made a point of talking up U.S. presidents then regarded by orthodox historians as second-rate or worse: Harding, Coolidge, Eisenhower. He wrote:

Eisenhower was the most successful of America’s twentieth-century presidents, and the decade when he ruled (1953-61) the most prosperous in American, and indeed world, history.

That planted in me the wish to read a full biography of Ike. I kept putting this off, though, perhaps because my desire to read about underrated U.S. presidents was sated by the researches I did in the 1990s on Harding and Coolidge. (I even read Carl Anthony’s biography of Mrs. Harding, which is more interesting than you”d think. She had an illegitimate child at age 20, and supported herself and the child by giving piano lessons.)

It was the author’s name that prompted me to read an Ike biography at last. Paul Johnson has been a companion”in the literary sense; he doesn”t know me from Adam”all my adult life. I”m a fan from way back: from the mid-1960s, when P.J. and I were both lefties.

He was a much more significant lefty than I was: editor of the weekly New Statesman, the main vehicle for intellectual leftism in Britain. I was a flat-broke math undergraduate with romantic issues, sitting in the student lounge at University College, London reading P.J.’s “Londoner’s Diary” in the Statesman.

(Offered the opportunity to ask P.J. a question 11 years ago, I raised one of his “Diary” remarks that had somehow stuck in my mind. He had written circa 1965 that there were just two things he was sure of: one, that money is the root of all evil, and, two, that the only cure for unhappiness is hard work. I asked: had he revised his opinion on either point in the subsequent four decades? His answer is here.)

In the 1970s P.J. and I both moved to the political right, from the New Statesman to the Spectator. Looking through the list of P.J.’s published books at Amazon, I believe I”ve read more than half of them. After that much acquaintance, you get to know a writer, warts and all.

There are definitely warts. Some of P.J.’s factual howlers are notorious: his claim, for example, in his History of the American People that Thomas Edison invented the telephone. Having written books myself, I”m more tolerant than the average about such things. Book publishers used to employ gimlet-eyed editors to catch authorial bloopers. Nowadays the poor author is on his own, naked before his own fallibility. You try it.

P.J. is also a dogmatic Catholic, and so believes things that strike us irreligious types as nutty. His 1996 apologia, The Quest for God, for instance, has a whole chapter on Hell, opening with the sentence: “There has never been a time when I have not believed in the existence of Hell.” He ponders the nature of the infernal region at length … though allowing that it may be uninhabited!

Still, it says something for the quality of P.J.’s prose that he can hold the attention of a reader who doesn”t believe in the existence of the thing he’s writing about.

Coming to the Eisenhower biography with all that baggage, what did I think of the book?

First, Eisenhower: A Life is short. The narrative matter occupies barely a hundred pages, discounting blank and title pages. You can”t really capture much of a man in that space, although P.J. does better than most would have.

A principal theme is of Ike as a ringer, in the racing-slang sense.

Ike consistently misled the press … in giving a general impression that he worked much less than he did … [Press Secretary] Hagerty enjoyed the deception procedure”almost as elaborate, and successful, as the one used on German generals before D-Day … As Nixon grasped early on, Ike took to deviousness with relish.

The ploy worked too well, leaving the American public with a vague recollection of Ike as a syntax-challenged golfer. In fact he was a brilliant, hardworking administrator, and highly intelligent. He was even a creative mathematician: see the index entry for “integral calculus” in Michael Korda’s biography.