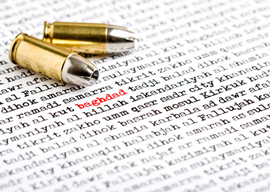

July 06, 2014

Source: Shutterstock

A single death, said Stalin, is a tragedy; a million deaths are a statistic. We know, alas, precisely what he meant by this cynical remark: it is beyond our human capacity to grasp emotionally, rather than intellectually, the suffering of more than a few people at a time. As soon as that number is passed, we strain to feel, rather than actually do feel, and a false note is introduced into our expressions of compassion or anger. We feel guilty that we do not feel a million times more strongly for a million people than we do for one, and so inflate our language. We strike a tinny note, and hearing it, we try to recover by striking an even tinnier one.

Thus we apprehend catastrophe by fragments and stories rather than by a global appreciation; one story is worth a table of statistics, at least for the emotional impact it has on us. We may despise ourselves because this is so, but it is so.

A couple of days ago I read in a French newspaper the story of Mushtaq al-Musil, a prisoner held in Badush, the large prison near Mosul. He had been in custody since 2003, when he was denounced anonymously to the Iraqi and American authorities as a member of Muqtada al-Sadr’s Shia terrorist militia, the so-called Army of the Mahdi. Whether he actually was a terrorist or not, I do not know: arms were allegedly found in his house, but I do not suppose that conviction by an Iraqi court of the time would count as decisive proof. Anyway, he was sentenced to 15 years” imprisonment.

By means of bribery of the guards, paid directly by transfer from members of his family by mobile telephone (isn”t technology wonderful at making life easier?), he was permitted to have a telephone, and every day he would speak to his brother on it, sometimes for hours at a time.

Then around 6 A.M. on June 10, he phoned his brother (a policeman in Baghdad) to tell him that strange things were happening at the prison. The guards were absent. At 8:30 he told his brother that he was free, and he had left the prison, though he was somewhat disturbed to see that the road to the city was deserted.

At 10:33, he told his brother that he had been forced by men in black to get into a truck along with other freed prisoners. His last words were, “I think it will soon be all over for me. Forgive me, brother, if I”ve ever done you any harm.”

From 10:45 to 3:30 in the afternoon, his oldest brother telephoned him continuously, but there was no answer. Then, eventually, an unknown man with a Mosul accent replied: “He’s dead. I have his telephone now.” His brother demanded to know what happened to him. “He and the others have all had their throats cut. There was blood everywhere. I don”t have the heart to look at the bodies again.”

At 5:30, his oldest brother phoned again, asking to recover his body, offering 5,000, then 10,000, and finally 50,000 dollars. “I don”t need your filthy money,” said the unknown man.

The brother then called the guard whom he had previously bribed to let Mushtaq have the telephone, and he put him in contact with a Sunni prisoner who had shared the same part of the prison as Mushtaq. This co-detainee described how he and all the other prisoners had been driven by the ISIS militia to a valley outside the city and how the Sunnis among them had pointed out the Shia. The Shia (Mushtaq among them) had then been shot. It was not true that their throats had been cut; that was a gratuitous detail to make Mushtaq’s brothers suffer slightly the more.

Most of the elements of this story are atrocious, and bring home the depth of human depravity, cruelty, and insensate hatred more vividly than mere figures could ever have done. Here were malignity and sadism dressed up as a cause so pure that it could justify any evil. Man is seldom worse than when joyfully inflicting misery in the name of an ultimate good.