January 21, 2014

Robert de Niro

Samuel Leistedt has my dream job.

The Belgian forensic psychology professor and his team watched 400 movies and diagnosed 126 characters as true psychopaths.

They concluded that many famous movie crazies don’t fit the diagnostic criteria. Psycho (1960), for example, is about a psychotic, not a psychopath; Norman Bates converses with”and dresses up as”his dead mother, and such delusions are characteristic of the former, not the latter.

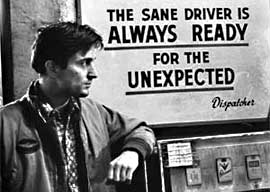

The same goes for Robert DeNiro’s “Travis Bickle” in Taxi Driver (1976). While they don’t mention it in the paper, the authors seem sympathetic to the critical theory that the film’s “happy” ending”or even much of the rest of the movie“depicts Bickle’s psychotic delusions of grandeur and not “real” events.

Forensic psychiatrists have been trying for years to disabuse laymen of the notion that Hannibal Lecter of Silence of the Lambs fame is a typical psychopath. Leistedt takes up that possibly lost cause here: no, the average psychopath is not a strangely seductive high-IQ gourmand with impeccable manners.

The Belgian team wisely excluded fantasy and “comic book” villains like Batman’s nemesis the Joker along with inexplicably immortal masked murder machines such as the Jasons and Michaels of slasher film infamy. Movie buffs should be impressed by the breadth of characters that did make the cut. In a world (sorry…) in which millions of people have never seen a film older than Star Wars, I was heartened to see names such as “Cody Jarrett” from White Heat (1949) and “Krugg” from The Last House on the Left (1972).

Yet that very buffdom means I can’t help but puzzle over some of these diagnoses. Take Peter Lorre’s career-making role as child molester “Hans Beckert” in Fritz Lang’s M (1931). Dr. Leistedt calls him “an outwardly normal man with a compulsion to kill.” Lorre was a gifted actor, but I question his ability to convincingly portray an “outwardly normal man” based on the accidents of physiognomy alone.

Lorre and Lang also saddle the character with decidedly extraordinary traits: The twitchy, taciturn Beckert skulks through the streets and ducks into doorways while loudly whistling “In the Hall of the Mountain King.” The titular “M” which his fellow (less perverse) criminals chalk onto Becker’s back to help vigilantes track him seems barely necessary. If anything, M helped accidentally solidify the public’s fatally flawed belief that child molesters are sinister-looking strangers.

Futhermore, while holding up Beckert as “realistic,” Leistedt dismisses Richard Widmark’s “Tommy Udo” in Kiss of Death (1947) as nothing more than a typical Hollywood caricature of a psychotic, one fashioned from cinematic shorthand: “bizarre mannerisms, such as giggling, laughing or facial tics.” Yet how is his character’s freakish trademark giggle any more “bizarre” than Lorre’s compulsive whistle?