January 12, 2014

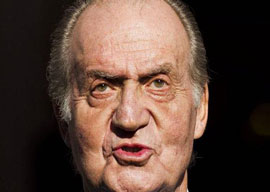

King Juan Carlos of Spain

The temper of the times is often revealed by small details in newspapers, and that is why (I tell myself) I still read them, though it is common wisdom that they are on the path to extinction, as dinosaurs were after the great meteor hit the earth 65 million years ago. At any rate, I hope that they will last me out.

Two days ago I read in a French newspaper an account of the present legal difficulties of the Infanta of Spain, Cristina. I haven”t followed the matter closely because questions of fraud and tax evasion (with which she is charged) are complex and boring, the Devil being in details that are tedious to master. Suffice it to say that I suspect any princess who marries a handball champion is courting disaster.

Naturally, republicans in Spain are using the case for all it is worth (and by all accounts successfully) to undermine the monarchy’s popularity: though illogically, for there is no reason to think that the presidents of republics and their close relatives are less corrupt than monarchs and their close relatives. Spaniards have only to look north of the Pyrenees to see that this is not so: The various corrupt practices of Giscard d”Estaing, Mitterand, Chirac, and Sarkozy were, and are, notorious. No one, as far as I know, has used them to suggest a restoration of the Bourbons in France. To object to institutions on the grounds that some of the people who represent or work in them are corrupt is either to reject institutions as such or to utter a cry of despair at human nature, to reject the notion of original sin.

But this was not what caught my attention in the article. Rather, it was what followed the statement that 2013 was an annus horribilis for King Juan Carlos. It described the annual military parade in Madrid:

Not only did this much-diminished man have to review the troops while in a sitting position, but in the course of his speech he stammered many times, confusing words and paragraphs. “These were worrying signs of senility and the metaphor of a faltering regime,” said the analyst, Ana Romero. This failed ceremony, the object of mockery of most of the media, reduced to nothing the Royal House’s attempts to improve the image of a limping king.

What the writer of the article failed to notice is that, if true, this reflected far worse on the media and on a public that approves of the media than it did on the King. For then we read:

After six admissions for surgery (three on his hip in 2013) in two years, Juan Carlos is a decrepit patriarch, for whom each public appearance is a torture.

Surely a man who has undergone so much pain at age 76 but nevertheless tries to carry out his duty is more worthy of compassion and respect (all the more so as no one denies the services he has rendered his country) than mockery. People who mock him because, and only because, he is frail both mentally and physically after six operations in two years at quite an advanced age are lacking either the most minimal powers of imagination or are callous to a quite horrible degree. This repellent callousness, no doubt covering itself with a patina of virtuous democratic sentiment, is the reverse face of the coin whose obverse is the sentimental moral adulation of ordinary people as inherently the victims of circumstance.

Another item, much shorter, in the same issue of the newspaper caught my eye. The headline was “A Belgian celebrates his euthanasia with champagne.” At first it all seemed very jolly and in its way admirable:

“Who would not want to finish with champagne, in the company of all his loved ones?” It was in this way that Emiel Pauwels, a 95-year-old Belgian, justified his choice to “celebrate” his death by euthanasia. The kingdom’s “oldest athlete,” European over-ninety 60 metre champion, died yesterday after a “festive evening.” A hundred friends and relatives were invited, and the photos show him smiling, a glass of champagne in hand. “It’s the best party of my life,” he declared.