November 14, 2012

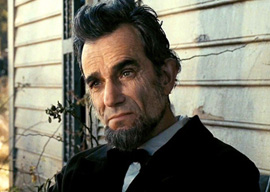

Daniel Day-Lewis

With his unimpeachable performance in Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln (which opens nationwide on Friday), Daniel Day-Lewis seems ready to become the first man ever to win three Best Actor Oscars. After his awards for My Left Foot in 1989 and There Will Be Blood in 2007, Day-Lewis is tied for the career lead with Spencer Tracy, Fredric March, Gary Cooper, Marlon Brando, Dustin Hoffman, Tom Hanks, Jack Nicholson, and Sean Penn.

Hollywood had never previously managed to make the 16th president seem interesting, so Day-Lewis’s delightful turn as a genial politician more crafty and good-humored than the Lincoln Memorial’s man of marble will be hard to beat for the Academy Award.

Abraham Lincoln’s sense of humor was documented in the countless books published by everyone who had ever encountered him. The challenge that Day-Lewis somehow overcomes is that the prairie politician’s jokes seemed corny even 150 years ago.

Nobody today knows much about what Lincoln’s body language looked like, but Day-Lewis’s version seems perfectly plausible to audiences, perhaps because he’s channeling the slightly creaky movements of the robot in Disneyland’s Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln attraction. And why not? We all saw Animatronic Abe as kids, so that’s what we expect.

The only shortcoming of Day-Lewis’s performance is that at six foot-oneish, he is about three inches shorter than the awkwardly tall Lincoln, who didn”t fit in most chairs, beds, and doors of his day. The 6″4″ Liam Neeson was long attached to Spielberg’s project, but the broad-shouldered Irishman would have been too physically imposing. (Why can”t America produce tall movie stars anymore?)

Day-Lewis is famous for the wonderfully demented lengths to which he will go as a method actor to stay in character for months at a time (such as having the long-suffering movie crew carry him around the set in his role as the paralytic in My Left Foot). Yet in the 2000s, his strength has become not method mumbling, but his superb breeding (he’s the son of poet laureate Cecil Day-Lewis) and classically trained diction. He’s unveiled sensationally stagey 19th-century accents in the roles of Bill the Butcher in Gangs of New York and Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood. Now he’s given Abe Lincoln a tenor voice ideal for rapidly, yet comprehensibly, dashing through complex and lawyerly sentence structures.

Lincoln had a precisely logical mind. Perhaps due to his being an intense re-reader of the limited number of high-quality books (especially Shakespeare and Burns) available to him in Indiana and Illinois, he also had great talent as a phrasemaker. On the other hand, Lincoln’s utterances tended to be knotted. It’s no anomaly that the Gettysburg Address, with its daunting ideas-to-words ratio, made little impression on those few who could hear Lincoln’s thin voice. His statements lacked the rhetorical cultivation that, say, Winston Churchill could absorb having grown up in the seat of empire.

Screenwriter Tony Kushner’s lines do justice to the intricacy of the historical Lincoln’s serious remarks, but even with the world’s best movie star delivering them, theatergoers will often wish they could pause and rewind.