November 23, 2011

The Descendants, with George Clooney as a Hawaiian land dynasty’s 1/32nd-Polynesian scion, has fans asking where writer-director Alexander Payne has been since 2004’s Sideways, which dispatched Paul Giamatti and Thomas Haden Church on one last trip to the Santa Ynez wine country. (Sideways was such an ideal combo of comedy and drama that it was remade line-for-line in Japanese. The only change was a relocation to Napa Valley because Japanese tourists don’t do non-world-class attractions.)

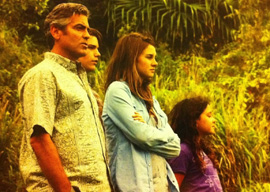

In Payne’s new dramedy The Descendants, Clooney plays Matt King, the great-great-great-grandson of a 19th-century Hawaiian princess who, rather than marry her brother in the incestuous royal Hawaiian way, eloped with a Yankee businessman. Her numerous, mostly blue-eyed progeny hold in trust 40 undeveloped square miles of lovely Kauai.

Clooney’s protagonist tries to uphold the King clan’s ancestral Protestant work ethic, driving his Honda Civic to his law office every day. His more decadent cousins have tasked him with selling their patrimony. Meanwhile, his wife is in a coma from a speedboating accident.

And he has had to withdraw his elder daughter from Punahou School, the flagship of Hawaii’s Protestant landowning caste. He doesn’t think much of her boyfriend, Punahou’s most reliable source of primo weed. (Eventually the father comes to accept the stoner dude. Who knows? He may grow up to be president someday.)

As usual, Clooney isn’t tremendously believable as one of life’s beleaguered losers. But you don’t hire Clooney to disappear into characters like Gary Oldman does. You sign up Clooney, a witty man, to promote your movie.

The Descendants had me wondering: Where has Hawaii been since the 1960s? It’s hard to explain to somebody who wasn’t a kid back then just how large the Fiftieth State loomed. For instance, 1966’s top-grossing movie was an adaptation of James Michener’s Hawaii, with Julie Andrews as a New England Congregationalist missionary disembarking in 1820s Honolulu. (It didn’t hurt box-office receipts that—strictly in the interest of anthropological accuracy—the ship is greeted by a bevy of bare-breasted native beauties.)

Famously, the Protestant preachers came to Hawaii to do good but wound up doing well. They married into the native nobility, then formed an endogamous ruling caste that still controls much of Hawaii’s acreage.

Hawaii wasn’t celebrated just for scenery, though. In the Civil Rights Era, Hawaii was seen as embodying a solution to racial strife: intermarriage. Michener, the bard of mainstream pre-1960s liberalism, ended his episodic panorama with the advent of a new man who unites in his person Hawaii’s multiple cultures:

…in Hawaii a new type of man was being developed. He was a man influenced by both the west and the east, a man at home in either the business councils of New York or the philosophical retreats of Kyoto, a man wholly modern and American yet in tune with the ancient and the Oriental. The name they invented for him was the Golden Man.