July 11, 2011

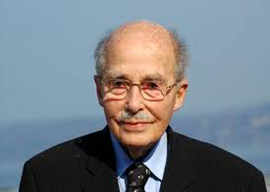

Archduke Otto von Habsburg

The San Fernando Valley in the 1970s was a very dull place. Hot and dusty, filled with lackluster architectural construction thrown together during the postwar housing boom, it was the last place I wanted to be.

Back in those far-off days, the LA Archdiocese’s paper, The Tidings, ran a column by the Archduke Otto von Habsburg, son of Austria-Hungary’s last Emperor-King.

My family was historically minded, and my upbringing gave me a hatred of the French Revolution and a love of the Habsburgs, Bourbons, and Stuarts. In high school in the 1970s, I became a monarchist. In the LA Central Library lurked such volumes as The Purple or the Red, Kings Without Thrones, and Monarchs-in-Waiting. I resolved to write to the Archduke Otto concerning issues political and religious. Off my note went into the post.

A response came back—and it was not a form letter. Instead, it contained cogent responses to the ramblingly naïve queries of a high-school lad in far-off Sylmar, California! This was the beginning of a regular correspondence that continued for six years (until after I left college) and sporadically ever since. On his birthday and Christmas in the past decade I made a point of sending him See’s Candies—a purely California product which he very much enjoyed. I had the privilege of meeting the Archduke twice: the first time in 1999, at the Vienna launch of his son the Archduke Karl’s unsuccessful run for the European Parliament. There, in his ancestors’ throne room, the heir of so much that is best in Western culture recalled our correspondence and expressed great pleasure at our finally meeting. The second time we met was in Rome in 2004, at the beatification of his father, the Emperor Karl. One can only imagine the emotions that ran through his mind on that occasion, but he was unfailingly gracious and attentive as ever.

In 2009, I made it to Budapest and visited the site where four-year-old Otto had stood at his parents’ coronation in 1916 in the St. Matthias Church. It was a potent reminder of all that he had lived through: war’s outbreak, his parents’ brief reign and attempts at regaining Hungary; his father’s death in exile; his own attempts to rally resistance to Hitler before and after the Anschluss; his warnings about communism after World War II; his work to create a united Europe that would be both free and true to its religious and secular traditions; and his father’s beatification.