March 23, 2011

In Win Win, Paul Giamatti (perhaps best known for 2004’s Sideways) plays a nice-guy lawyer, Mike Flaherty, who also coaches his old high school’s wrestling squad. His family-law solo practice isn”t generating enough revenue to pay his health-insurance premiums. In a moment of ethical weakness, he persuades a judge to make him the court-appointed guardian of a wealthy but senile client who wants to stay in his own house. He then dumps the codger in an old-folks” home so he can pocket the $1,500 monthly stipend without doing the work.

If Win Win were a Coen Brothers movie, this single lapse would set in motion a train of inexorable consequences that would eventually kill a half dozen people. But writer-director Tom McCarthy (2003’s The Station Agent, with the memorable dwarf actor Peter Dinklage, and 2008’s The Visitor, for which Richard Jenkins received a Best Actor nomination) makes wry little dramedies empathetic toward characters” foibles. Critics refer to such films as “humanist” without explaining what this kind of movie has to do with the vaulting ambitions of Renaissance Florence.

Mike’s attempt at malpractice drags him into helping out his intended victim’s dysfunctional family. Dropping by the old man’s house to make sure the pipes don”t freeze, Mike finds his client’s 16-year-old grandson sitting on the steps. Young Kyle ran away from his home in Columbus when his mother went into rehab.

“A couple of loose ends in the plot could have used Charlotte Brontë as a script doctor.”

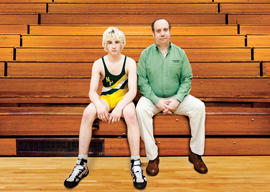

The kid’s deadpan personality makes him seem damaged by abuse, so Mike and his wife decide to put him up in their basement. Yet when Kyle asks if he can practice with Mike’s wrestling team, the youth’s flat affect is revealed as brusque self-confidence. He is an Ohio state champion wrestler, much to the exhilaration of Mike, who has never had an outstanding athlete on his squad before.

(High-school wrestling looks awfully gay but isn”t. Win Win makes a couple of quick, uncomfortable jokes to acknowledge audience prejudices, then moves on.)

Someday, an outstanding movie will be made about how coaches are torn between coaching and recruiting”the downside of The Blind Side. Landing one great recruit can make a coach look like a genius, ensuring himself a long line of quality recruits even if he can”t actually coach.

Win Win isn”t that film. Its third act veers off to yet another storyline in which Kyle’s mother shows up to claim her inheritance. In last week’s review of Jane Eyre, I called for more movies about legacies, so I can”t complain.