January 10, 2011

Who’s the leading leading man these days?

Having sat through all 147 dolorous minutes of Biutiful, Alejandro González Iñárritu’s follow-up to 2006’s Babel (a pretentious clunker gifted with seven Oscar nominations), I”ll nominate Javier Bardem. The Spaniard won”t win Best Actor this year to go with the Supporting Actor statuette he took home three years ago for playing the relentless killer Anton Chigurh in No Country for Old Men, yet I likely would have walked out of Biutiful if anybody else had been starring in it.

Anointing Bardem as the movie star of the moment isn”t terribly counterintuitive. After all, Penelope Cruz just married him. Still, what it is about Bardem’s visage that distinguishes him from earlier soulful brutes such as De Niro, Depardieu, and Crowe?

Biutiful isn”t a very good movie, but it was envisioned around its star’s looks. González Iñárritu has numerous flaws as a filmmaker, but the man does have an eye. As Bardem’s hero”an illegal-immigration coyote who manages Senegalese street peddlers and Chinese construction workers”tries to do right by the people in his world before he leaves it, it becomes clear from all the lingering shots of religious icons on the walls that González Iñárritu wasn”t only thinking about Bardem’s acting dexterity when he wrote the role. He was thinking about Bardem’s nose.

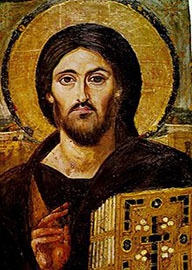

Going back at least 1400 years to the Byzantine Christ Pantokrator encaustic painting in a monastery on Mt. Sinai, a prominent nose that is vertically long but relatively flat in depth has been a standard part of Christian iconography. In 1995, Bardem’s nose got flattened in a disco punch-out, but his new nose has hardly hurt his career. (Bardem says he doesn”t know who slugged him, “but all I can say to the guy is, “Jesus, man, thank you.””) Combined with his rugged brow ridge and severely sloping forehead, Bardem now looks like Caveman Jesus.

Going back at least 1400 years to the Byzantine Christ Pantokrator encaustic painting in a monastery on Mt. Sinai, a prominent nose that is vertically long but relatively flat in depth has been a standard part of Christian iconography. In 1995, Bardem’s nose got flattened in a disco punch-out, but his new nose has hardly hurt his career. (Bardem says he doesn”t know who slugged him, “but all I can say to the guy is, “Jesus, man, thank you.””) Combined with his rugged brow ridge and severely sloping forehead, Bardem now looks like Caveman Jesus.

Although Biutiful is better than Babel, it’s still a miserable slog. González Iñárritu’s very Mexican obsession with death leads him to inflict tribulations upon his doomed protagonist: terminal prostate cancer, a bipolar ex-wife who is sleeping with his sleazeball brother, and a reputation in his slum for being able to talk to the newly dead. This gets him invited to many funerals, which doesn”t improve his mood. Yet not only is Bardem compelling in a Casablanca-style role as a shady operator who turns out under stress to be a saint, the actor’s Christlike profile even makes some sort of sense out of González Iñárritu’s masochistic Mexican Catholic aesthetics.