June 22, 2016

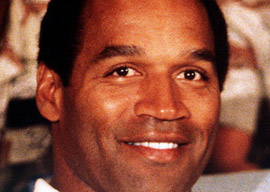

OJ Simpson

I”ve been pointing out for years that O.J. Simpson’s 1994 white Bronco run for the Mexican border from his lawyer Robert Kardashian’s house was a turning point in American cultural history, spawning the Kardashians, Caitlyn Jenner, and much else that you could be watching on your TV right now.

It was the point when the world figured out once and for all that those countless channels being opened up on cable could be filled with all sorts of cheap-to-produce crud and people would watch.

This is the year that the media finally figured out this bit of its own history and is running various lengthy miniseries and documentaries about O.J. Simpson. But that raises the problem of explaining to young people who O.J. was and why.

All good young people today know that America was virulently racist until, roughly, last week.

But the O.J. story is hard to fit into The Narrative of endless white racism. Here’s a black man who was wildly popular with white Americans in the distant past.

The New York Times Magazine offers an attempt, “Why “Transcending Race” Is a Lie,” by a young black writer to make the O.J. story fit everything he’s learned from master historians such as Ta-Nehisi Coates. Greg Howard explains:

Every black person, successful or not, has to overcome a steep handicap; the idea of racial transcendence is anchored in the fallacy that the handicap is blackness itself, rather than a society that terrorizes and undermines blacks at every turn.

Personally, I had thought that O.J. had terrorized and undermined Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman while trying to decapitate them, but now I guess I see it in the big picture.

Seriously, the reason the conventional wisdom has such trouble making sense out of the Simpson story is because O.J. epitomizes how beloved blacks had become by American whites in the last third of the 20th century…and how often blacks then let whites down.

Meanwhile, over at Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight, they”re trying to use advanced statistics to figure out why all the old folks had heard of O.J. even before his murder trial. Greg Guglielmo asserts that “O.J.’s Football Fame Was Mostly Based On Two Great NFL Seasons,” 1973 and 1975.

Nah, a half-dozen years before he peaked in the pros, O.J. had been the most famous college football player since Red Grange in the 1920s. O.J.’s two seasons with the University of Southern California Trojans in 1967″68 were incredibly well publicized.

Color television and instant replay were introducing a new golden age of spectator sports, so O.J.’s 64-yard run to beat #1-ranked UCLA was replayed over and over in “ABC Color Slo-Mo.” In 2016, there’s nothing novel about the play, but 49 years ago O.J.’s combination of strength and speed looked like the future.

Indeed, O.J. had been immediately recognized as the future of not just football but of American sports from early in his first college season.

Much of that had to do with playing in the media capital of Los Angeles, and Simpson’s good looks and sociopathic charm didn”t hurt. (Still, contrary to what many of the more immature pundits have suggested, O.J. was hardly the first popular black athlete in America. Baseball player Willie Mays, for example, had been adored since The Catch during the 1954 World Series.)

But if you simply look at O.J.’s college yardage statistics, his acclaim isn”t too surprising.

I watched O.J. rush for 238 yards on 47 carries against #13 Oregon State at the Coliseum in 1968. Those were science-fiction numbers by previous standards. (By the way, my ticket cost $0.55.)

For example, the previous season, in 1966, the top running back in the Heisman Trophy voting, third-place finisher Nick Eddy of #1-ranked Notre Dame, had rushed for all of 553 yards. The other three running backs in the Heisman top 10″Floyd Little of Syracuse, Clinton Jones of #2 Michigan State, and Mel Farr of UCLA”rushed for between 784 and 811 yards.

In 1967, in contrast, O.J. rushed for a spectacular 1,543 yards. In 1968, when they finally gave him the Heisman Trophy (which became the most notorious single trophy in sports when O.J. used subterfuge to delay the Goldman family auctioning it off as part of their huge civil judgment against him), he rushed for 1,880 yards and 23 touchdowns in 11 games.

There were several reasons why O.J.’s numbers were so outlandish compared with what college fans had been accustomed to.

First, O.J. was really good. He weighed 205 pounds and yet was a near-world-class sprinter. His USC track relay team”with future NFL star receiver Earl McCullouch, Fred Kuller, and anchorman Lennox Miller of Jamaica, who won silver and bronze in the Olympic 100-meter dash”set a world record in the 4×110-yard sprint relay.

Before the late 1950s, it was assumed that speed and strength were negatively correlated. Carrying a lot of upper-body musculature, while good for straight-arming would-be tacklers, would only slow you down, right? It’s basic physics.

But then bulky black speedsters like 1964 Olympic 100-meter champion Bob Hayes started to come along.

O.J. wasn”t the first of the big, fast black running backs. The even-heavier Jim Brown had been putting up huge numbers in the NFL for nine seasons before retiring in 1966 to be a movie star in films like The Dirty Dozen and Ice Station Zebra. But by 1967 sports fans were fully ready for the new type of black running back pioneered by Brown and Gale Sayers, and O.J. was in the right place at the right time.

Second, college football offensive statistics hadn”t been very good before 1965 because players typically played both offense and defense. During WWII, Army (i.e., the West Point military academy) had so many good football players that the coach had introduced separate platoons on offense and defense. But the NCAA banned platooning from 1953 to 1964, so offensive skill-position players couldn”t specialize, which made them less skilled. And more tired.

Therefore, the statistics of earlier Heisman Trophy winners appear curiously muted to modern eyes. For example, 1959 Heisman Trophy winning running back Billy Cannon of LSU rushed for 598 yards for the season. But you have to keep in mind that Cannon was also playing defensive back, kicker, and punter.

O.J. didn”t waste his time doing much for USC besides running the football (and running track in spring). Oddly, when he was drafted number one by the Buffalo Bills of the NFL, the coach decided that his new celebrity was a distraction from, in his view, the real talent on the team, quarterback (and future GOP vice presidential nominee) Jack Kemp. So O.J. was used as a decoy at wide receiver, but he couldn”t catch the ball.

Eventually, Kemp went into politics, the coach was fired, and the new coach, Lou Saban, intelligently put O.J. at tailback, where he racked up the NFL’s first 2,000-yard rushing season.