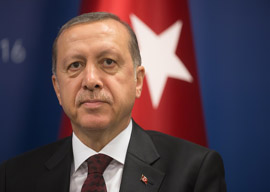

July 22, 2016

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan

Source: Bigstock

Turkey matters, for obvious reasons: its size (population: 80 million); its geographical position; its influence in the Middle East; its membership in NATO and the fact that it has the second-largest army in the alliance, while some 60 American hydrogen bombs are stored in Turkey (safely, one hopes). Moreover, Turkey has absorbed more than 2 million refugees from Syria”fairly enough, one might add, since Turkey has helped to prolong the civil war there with the support it has given to the so-called moderate opposition to President Assad, while at the same time hampering (to put it mildly) the Kurdish campaign against the Islamic State. Making sense of Turkey is not easy.

For a dozen years President Erdogan has been in charge, first as prime minister. In the early days he was regarded as a moderate and reasonable leader”an Islamist, certainly, but a democratic one. Even so, from the first, some observers were worried. The great achievement of Kemal Ataturk, who, after the 1914″18 war, created the modern Turkish state out of the ruins of the Ottoman Empire, was to effect a clean separation between politics and religion. Turkey was a Muslim country, but the state was secular. Religion was respected but only as a private matter and accorded no special status or rights. The whiskey-drinking Kemal decreed that the army was the expression of the nation and the guarantor of secularism. Modernity required that religion be confined to private life. Several times in the second half of the 20th century, the army intervened”violently by means of a coup”to ensure that Kemal’s secular state was not corrupted by Islam.

Erdogan has changed all that. He has gradually pursued an Islamist agenda, advancing Islamism salami-style. He has purged the armed forces, several times. He has attacked the freedom of the press, by means of censorship and the imprisonment of opposition journalists. He has restricted civil rights, to the dismay of the Westernized middle class. Yet, though he is ruthlessly authoritarian, it can”t”yet”be said that he is undemocratic. His Justice and Development Party (AKP) has won elections (or been the senior partner in coalitions), and nobody doubts that he has huge popular support from the peasantry, the working class, and conservative Muslims. So the USA and Europe have worn kid gloves in their dealings with him. His policies may be deplored, but he has maintained stability”and we need a stable Turkey.

Now we have last weekend’s botched coup d”état. If it had succeeded, the West would have been in an awkward position: reluctant on the one hand to approve the violent overthrow of a democratically elected government, relieved on the other hand to see Erdogan go, though this is something we can”t now admit, especially since we are, nominally anyway, in favor of democracy in the Muslim world.

The coup itself has predictably spawned conspiracy theories. Was it a “false flag,” engineered by Erdogan and his allies to give them an excuse for a further crackdown and the elimination of opponents of his Islamist program? It came close enough to success to make this unlikely. Erdogan himself claims that he was only minutes away from being killed or taken prisoner. Perhaps he was, but then again, perhaps he wasn”t. Certainly it does him no harm to present himself as a near victim, saved by God.

He has advanced his own conspiracy theory: that the coup was engineered by his rival, Fethullah Gulen, a Muslim cleric now living in exile in Pennsylvania. Gulen’s Hizmet movement, usually described as moderate, has many adherents in the armed forces, the civil service, and the judiciary. Erdogan has called it a “parallel state structure.” Akin Ozturk, commander of the Air Force till last year and still a member of the High Military Council, was among those immediately arrested and paraded”stripped of his uniform and in civilian clothes”before the cameras. According to state media, he is a “leading Gulenist” who has confessed that he was one of the leaders of the coup. Suspiciously quick, you may think.

But then everything about the government’s response to the failed coup has been just that”suspiciously and alarmingly quick. Within hours of the coup’s failure, 6,000 military personnel were rounded up and detained, and more than 2,500 judges were dismissed. Since then, a further 103 generals have been arrested, while some 9,000 civil servants, 8,000 police officers, and at least thirty of Turkey’s eighty provincial governors have been dismissed. All, according to the government, are “Gulenists.”

It stinks. It stinks of foreknowledge. It’s incredible that such long lists of suspect persons could have been compiled in a couple of days, incredible that decisions to make these arrests and order these dismissals could have been implemented so quickly in the unsettled state of the country, in the immediate aftermath of an attempt to overthrow the government and end the Erdogan regime.