October 10, 2013

Nathan Bedford Forrest

Here is a thing that happened in the Civil War. If you know your Civil War minutiae, it”ll be familiar to you, in which case I beg your pardon. I can”t resist a good story.

A young lieutenant of the war angered his general by abandoning two artillery pieces to the enemy. The general ordered the young officer to be transferred out of his command. Feeling his honor insulted, the lieutenant asked for an interview. The general obliged.

When they met in one of the headquarters buildings, the lieutenant demanded to know the reason for his transfer. The general refused to tell him. Enraged, the young man pulled out a pistol and shot the general. “The ball entered the left hip, traveled in the vicinity of the intestines, and went out again.”

Before the lieutenant could fire again, the general reached out with his own left arm, grabbed the pistol hand, and forced it away from him. With his right hand he had been carrying a closed pocketknife. Using his teeth, he pulled out its biggest blade and stabbed his opponent in the belly, “ripping it open and perforating the bowels.” Dropping his pistol, the lieutenant staggered out into the street and made it across into a tailor’s shop, where he collapsed.

The general, meanwhile, had shown his gunshot wound to a doctor, who declared it dangerous. The general ran out of the building, grabbing a pistol on the way, and forced his way through the crowd of gawkers at the tailor’s shop. “Get out of my way,” he was shouting. “He’s mortally wounded me, and I aim to kill him before I die.” The lieutenant managed to leap out of a window, the general firing at him as he went.

The lieutenant died of sepsis two days later. Near the end he asked to speak to the general, who was recovering from his bullet wound. The general agreed, and his hospital bed was carried in to where the lieutenant lay. The young man begged his commander’s forgiveness. The general “leaned over the bed and wept like a child.” He told the lieutenant he forgave him freely and that his heart was full of sadness.

Self-preservation, the unconscious command of the wilderness, had made him kill one of his boys.

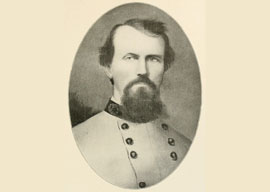

The general in that story was Confederate cavalry commander Nathan Bedford Forrest. I took the quotes there from Andrew Lytle’s biography, first published in 1931.

Forrest knew all about the wilderness. His father was one of those restless pioneers who felt the urge to move on west when he could see the smoke of his neighbor’s chimney. “West” and “wilderness” at this time”Forrest was born in 1821″meant the backcountry woodlands of what we nowadays call the Southeast, from which Andrew Jackson had evicted the Indians. Forrest grew up in cabins in west Tennessee and north Mississippi, the family making their own clothes, shoes, and candles, and killing their own meat. Education was a year or two in the “log academy.”

As that opening story illustrates, Forrest was a fearsome and fearless character. My Taki’s Mag colleague Fred Reed, writing once of his own time in the military, mentioned occasional encounters with the hardest of the hard men: still, quiet-spoken fellows, watchful, economical of movement, scary as all get out. I”ve met one or two in my own travels, and one or two is quite enough. I think Forrest was of that company. Read Lytle’s account of his being wounded at Shiloh.