December 12, 2013

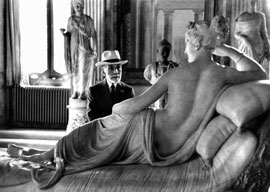

Bernard Berenson

Cohen, Rachel. Bernard Berenson: a Life in the Picture Trade. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013.

Berenson’s story is one of the most fabulous within living memory. It has everything: poverty, riches, high culture, high society, mystery, love, pain, two World Wars, infidelity, triumph, and his own magnificent sense of failure.

Berenson was born in 1865 in Lithuania, into a poor Jewish family who emigrated to Boston in 1875. Berenson was quick and clever but his schooling was patchy, and he managed to get himself to Boston University largely by voracious reading in the public library. A year later, he transfers to Harvard. This is the first great mystery of his advancement.

“It seems that he met Edward Warren,” writes Cohen, “a wealthy Harvard student just a few years older than himself, with whom he shared an interest in classical antiquities, and that Warren generously offered to pay the fees….” Warren was later the principal funder of Berenson’s first trip to Europe and also Berenson’s first client.

What Cohen doesn”t do is illuminate this sudden, essential relationship. Nor does she tell us that Warren was a pioneering homosexual who established a famous gay ménage in England and bequeathed an important collection of Greek erotic vases to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. He must have been in love with Berenson. She does mention Berenson’s visits to stay with Warren when the latter was at Oxford University and later on cites Berenson’s own account of his general relationship to homosexuals: He was occasionally tempted in his youth but never succumbed because of the social risk. Berenson wasn”t prim about it, often in later life mentioning with a twinkle that Oscar Wilde had made a pass at him.

Nonetheless, it is clear that the most important influence on Berenson’s early development was the homosexual milieu of aesthetes, collectors, and intellectuals on both sides of the Atlantic. Many of them went to live in Mediterranean Europe after Wilde’s imprisonment in 1895. Through one of its members, Logan Pearsall Smith, Berenson met his future wife Mary, who was Logan’s sister. (The other sister married Bertrand Russell.) The bible of this group, and the most important single book in Berenson’s life, was The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry by Walter Pater, also a homosexual. He first read it at school and from it emerged his twin loves for English literature and Italian painting. But he was mortified that Pater rebuffed him on his visit to Warren at Oxford.

Berenson converted to Episcopalian Christianity in his second year at Harvard, and later to Roman Catholicism; but his temperament was pagan and humanist, and if he did have a religion, it was the religion of art. He studied it closely”often, he said, in a state of “cosmic emotion.” His temperament was pagan and humanist. He had many affairs and they constantly overlapped, causing consternation all around. Cohen is brilliant in threading these complexities together on the international carousel of the beau monde, though I found her index a bit hit-or-miss.

Clearly Berenson had a passionate need for women, while his life of art, travel, spiritual delicacy, and millionaire connections was far from unattractive. But we never learn what sex really amounted to for him. He was small, fussy, of unreliable health, and given to rages, and many of his women seem more like guardians, assistants, or benefactors. After Frank Costelloe’s death, he married Mary but told her he didn”t want children, nor her two daughters either. Berenson’s greatest companion was probably Nicky Mariano, a librarian, nurse, housekeeper, and saint rolled into one. He was more comfortable with women than with men, because men were a battle.

In the picture trade Berenson became the perfect hinge. The great American collections were put together mostly in the early twentieth century, and substantially through his knowledge and help at the European end via an official dealer. First Isabella Gardner of Boston became infected by the Italian enthusiasm, then names such as Henry Huntington, J. P. Morgan, and Andrew Mellon enter the frame. Berenson worked with Colnaghi’s but by the time he set up with Lord Duveen in 1912 the sums involved could be colossal”several hundred thousand dollars for a really major work. During the First World War the Berenson-Duveen alliance managed probably the biggest shift in ownership of major Italian pictures since the lootings of Napoleon. Most of the works involved went to the USA.