June 27, 2012

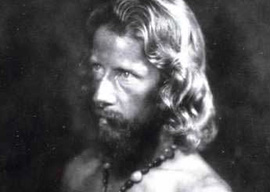

eden ahbez

One of the biggest changes of my lifetime has been the decline in the speed of social change. Today it’s easy to agree with Ecclesiastes that “What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.”

Yet that was once heresy. In high school, we were assigned Alvin Toffler’s 1970 bestseller Future Shock about how the late 1960s” tumult was a harbinger of the ever accelerating waves of change that would soon be overwhelming us. It seemed convincing at the time (and Newt Gingrich may still be a true believer), yet it didn”t really happen.

Instead, mass society fragmented and thereby stabilized. My cousin, for example, remains a hippie, and he’s recently talked his mother into wanting to go to Burning Man. Today, nobody much cares: Burning Man seems less shocking than funny.

Yet when I was a small boy, virtually every male in America, except perhaps violin soloists, had short hair.

It’s difficult to make clear just how big a deal hair length was in the 1960s. When I was six in 1965, my family went to England. We were sitting around at Heathrow waiting for our flight back to the US when a young man with collar-length hair walked into the waiting room. “It’s a Beatle!” screamed a girl. The excited crowd surged toward John, Paul, George, or, possibly, Ringo. I dispatched my mother to get the Beatle’s autograph. She returned bearing the signature “Peter Noone,” the lead singer of Herman’s Hermits.

The point of this anecdote is that in 1965 so few males had hair covering two-thirds of their ears that transatlantic travelers assumed that anybody who did must be a rock star. (And we were right.)

I can pin down when rock fans started to let their hair grow. Buffalo Springfield’s remarkable single “For What It’s Worth” (”Stop, children, what’s that sound?”) is usually thought of as an early Vietnam War protest song, but it was actually inspired by the Sunset Strip curfew riots over the planned demolition of the Pandora’s Box nightclub. Even in November 1966, however, a mob of protesting Los Angeles rock fans looked clean-cut.

That must have been the last time they got their hair cut. In the summer of 1967, some visitors wanted to “go see the hippies,” so my parents drove us over Laurel Canyon to Sunset. The Strip was jammed with us tourists agog over the longhairs.

After a while, though, you got used to odd new social phenomena like this sweeping the world. In fact, soon everybody expected it. A decade after 1967’s Summer of Love, for instance, the media were all primed for punks to take over. After all, an entire ten years had gone by! (That was 35 years ago.) In 1979, everybody was told to dress in 2 Tone black-and-white clothes and listen to ska, but diminishing returns were visibly encroaching.

Yet where did hippies come from? Were they a totally novel development, as they were portrayed at the time?

In 1948, jazz crooner Nat King Cole was on Top of the Pops for eight straight weeks with the single “Nature Boy.” The song became a standard and was recorded by Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, and Peggy Lee. (Much later, director Baz Luhrmann had a haggard Ewan McGregor type out the chorus at the end of his 2001 film Moulin Rouge.)