January 20, 2017

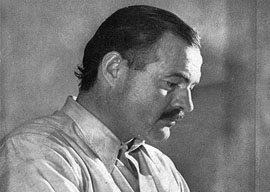

Ernest Hemingway

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Like many who had read, enjoyed, and admired Hemingway, I read A.E. Hotchner’s memoir Papa Hemingway soon after it came out. That would have been four or five years after Hemingway shot himself. Even before then I doubt if many bought Mary Hemingway’s loyal-wife explanation that the gun had gone off accidentally while he was cleaning it. This didn”t hold water. Hemingway had handled guns since he was a boy, and no matter how confused he may have been, he knew to check that a gun wasn”t loaded before he started to clean it.

The first half or so of the Hotchner memoir was exhilarating to read when you were in your 20s. You got a sense of Hemingway’s vitality and the fun you might have in his company. Naturally one would have liked to have had that experience, though even then I may have suspected that he mightn”t have had much time for me. The second half was sad, painful even, if not as tough to read as it must have been to live. More on that later.

I don”t know if young people today read Hemingway. No doubt his opinions and attitudes are anathema to many: Wildlife, for instance, is to be conserved, not shot for fun. Hemingway, the Great Hunter, is not an attractive figure, and even when it was first published in 1935, Green Hills of Africa lost him admirers, among them Edmund Wilson, who panned it.

It’s hard to realize now that it’s almost a hundred years since his first short stories appeared. They remain wonderful. He did more with less, with fewer words, than anyone else. No prose writer was ever better at making the words come off the page than the young Hemingway. Like many writers, I have come to value economy more the older I get, and in these stories Hemingway got rid of all inessentials; marvelous. Later he lost the knack and became garrulous. The Dangerous Summer, his account of a season spent following the bulls and the rivalry between Antonio Ordóñez and Luis Miguel DominguÃn, goes on and on and on. There was a recovery”late magic”with his Paris memoir, A Moveable Feast, though it’s not clear just when parts of it were written. Still, if you can set aside the bitchiness about other writers, notably Scott Fitzgerald and Ford Madox Ford, it’s a lovely book: “When spring came, even the false spring, there were no problems except where to be happiest.” One feels it should always have been that way with him.

It wasn”t, of course. Something went wrong with him in middle life. He took the wrong fork in the road when he set himself to write big novels. Getting into the ring with Tolstoy wasn”t really for him. As a writer he was a short-haul man. Being rich and world-famous didn”t help. It took him away from his material”I prefer him fishing for trout in the Big Two-Hearted River to hunting marlin in the seas off Cuba. Moreover it thrust him into the public eye, often to his embarrassment. He was an essentially private man who became a celebrity, resented this, and yet played up to it. The young Hemingway stayed in cheap apartments, hotels, and country inns, the older one in the Paris Ritz or the Gritti in Venice. The change didn”t help his writing.

Then he was hit on the head far too often, from the time a skylight in his Paris apartment collapsed on top of him, then through the traumas of the war against Germany to the plane crashes in Africa. We know a lot more now about head injuries and the damage they can do to the functioning of the brain than they did then. And finally there was alcohol, the good friend who can turn treacherous enemy. It’s no wonder that, photographed in his 50s, Hemingway seems like a man twenty years older, with a puzzled and pained look in his eyes.

So the second half of Hotchner’s memoir is a sad, depressing story of a crack-up and breakdown, all the more wretched because Hemingway, sometimes at least, understood what was happening to him. There’s a wretched moment when he tries to write something”just an ordinary letter, as I recall”and turns away from his writing desk with tears in his eyes, muttering that he just can”t do it, the words won”t come.