August 08, 2018

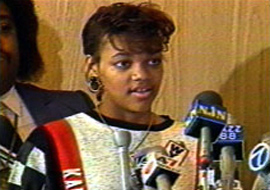

Tawana Brawley

Source: Wikimedia Commons

I’ve figured out a way to quantify how Establishment news organizations manipulate the contents of our minds: just track the use of tendentious phrases over the years.

Since 2016, there has been much talk of “fake news.” For example, The New York Times used the phrase “fake news” 901 times in 2017. Both sides of the political spectrum believe the other is outright making up events that never happened to promote their worldview.

That does happen…to some extent. For example, many of the most publicized hate crimes blamed on white men in recent decades have been either outright hoaxes or badly misreported.

A subtle but likely more important issue, however, is the question of which true news gets emphasized. There is always vastly more news than a person can remember. Thus your picture of reality is inevitably distorted to some extent by the power of the media, what I call the Megaphone, to pound over and over into your head certain true news, but not other true news.

Moreover, the press furnishes us with convenient concepts, such as “white privilege,” that make it easier to remember the facts they prefer you to know and harder to remember the facts that undermine the concepts.

For example, consider two black teens who once were true news.

In 1955, Emmett Till was murdered by two white men who were quickly acquitted, making his story memorable for being one of the last examples from a long era of state-excused white-on-black civilian violence over black males hitting on white females.

In 1987, Tawana Brawley launched our present era of making up hate hoaxes against whites by claiming that the reason she got home late was because she was being gang-raped by six white policemen.

Which incident is more rationally relevant to 2018? But which does the prestige media consider more au courant?

Tracking the numbers isn’t as easy as it ought to be.

In 2012, The New York Times graciously offered a tool called Chronicle for graphing its frequency of use of words since 1851. But as I pointed out in 2016, that made it almost too easy to document the Times’ increasing obsession during the Late Obama Age Collapse with words such as “racism,” “sexism,” and “transgender.” By 2015, in the sound of the Establishment suffering a nervous breakdown, the NYT was treating “racism” as five times more newsworthy than it had in 2011.

Not long after, the Chronicle web page was disabled.

Google offers its Trends to track search requests over time, but I’m less interested in measuring what the public asks for than what the media offers it.

Google’s Ngram helpfully graphs word usage in books, but its last full year of data remains 2007. The striking differences in elite fixations before and after Obama’s reelection are invisible to it.

So, I wound up using Google to do a brute-force search of each year in this century, plus 1980 and 1990, restricting the site to nytimes.com. (Bing and the New York Times search system give similar results, while DuckDuckGo doesn’t offer an obvious way to search one year at a time.)

What did I find? In 1980, the name “Emmett Till” did not appear in the pages of the NYT. In 1990 it showed up twice, and in 2000 four times.

From 2004 through 2012, the Times mentioned this old incident an average of nine times per year, and from 2013 to 2016 almost two dozen times per year.

Last year, “Emmett Till” appeared in 72 different Times articles. And this year is on track for 92 stories about the 63-year-old tragedy.

In contrast, the name “Tawana Brawley” might seem of slightly less antiquarian interest. The New York teen launched the modern era of antiwhite hate hoaxes in 1987, a few weeks after the publication of the late Tom Wolfe’s Bonfire of the Vanities best-seller about the “hunt for the Great White Defendant.”

The talented young race-racket activist Al Sharpton, the basis for Reverend Bacon in Bonfire, latched on to Tawana’s tall tale and turned it into a huge national brouhaha before it was utterly debunked and her half-dozen victims exonerated.

For a couple of decades, this instructive New York-area story was mentioned in the NYT (often in profiles explaining how Reverend Al had matured since his Tawana Brawley days, or occasionally in references to Wolfe’s magnum opus) about half as often as Emmett Till.

But in the 2010s, Tawana Brawley has come up in only 15 articles versus 249 mentioning Emmett Till.

Now, The New York Times would no doubt answer that it is merely responding to the great surfeit of events related to the Emmett Till case, such as a spat over whether a white artist should be allowed to display a painting of Emmett or whether only black painters should make money off the sacred subject.

On the other hand, the Times takes pride that it traditionally sets the agenda for the rest of the news business. So if the Times says that in 2018 Emmett Till is breaking news while Tawana Brawley is ancient history, lots of other influential media folks will follow its lead.

Moreover, whether you find Emmett Till or Tawana Brawley germane today can depend upon what concepts you have in your head for organizing the blooming, buzzing confusion of the world.

Why has the frequency of “Emmett Till” in the Times risen from a name referenced annually in the late 20th century to one mentioned monthly in the early 21st century to the name’s remarkable 2018 status as being as omnipresent in the news (55 mentions so far) as Chief Justice John Roberts (57 mentions)?

The growth of “Emmett Till” has correlated closely (r = 0.88) with the similarly increasing ubiquity of the phrase “white privilege.”

The term “white privilege” has been around for a long time, but the NYT didn’t obsess over it until recently, using it only once in 2000 and three times in 2010. Then it exploded in popularity with Times writers and editors in 2013 and is headed for about 60 usages this year.

If your head is stuffed full of the notion of “white privilege,” it’s only natural to remember “Emmett Till,” and vice versa.

“Emmett Till” and “white privilege” are mutually reinforcing pieces of the mental architecture of the average NYT reader. If you ever feel twinges of skepticism about the current stress on “white privilege,” just remember how Emmett Till’s murderers got off due to their white privilege and your doubts will recede.

Or if you start to wonder whether the reason we keep hearing over and over about this Eisenhower-era case is that it’s increasingly a man-bites-dog story, just remember how much everybody talks about “white privilege” all the time. So there must be many examples more recent than 1955, but the white male power structure is keeping them a secret. Or something.