February 06, 2013

Economist Gregory Clark’s 2007 book A Farewell to Alms features a study of English wills in 1200-1800. He found the highest numbers of grandchildren among successful farmers, the rural equivalent of the bourgeoisie. Lineages of farm laborers tended to die out from lack of opportunity to marry, while aristocrats tended to kill each other off. Thus today’s English, such as Dr. Sykes, tend to be descended from respectable non-aristocrats: the kind of landowners who married carefully, lived carefully, and passed on their property carefully.

On the other hand, families wracked by infidelity may have been less likely to survive due to lower paternal investment in children. (But by 1870, the poor were having more surviving children than the rich.)

A 1999 Mexican study suggests that certainty of paternity correlates with social class. The well-to-do in Nuevo Leon kept track of their families almost as well as Germans, with only about four percent paternal misattributions. In contrast, 20 percent of the Mexican poor aren”t who they seem.

A more subtle issue in making sense of the wide range of estimates is the question of “misattributed by whom?” The odds of getting the biological father’s identity wrong are least likely for the mother, next lowest for the presumed father, then the child, and highest among outsiders.

For example, studies based on medical crises where the child’s life is at stake might come up with estimates closer to the mother’s misattribution rate. Pediatric cancer clinics are experienced at making it clear to mothers that they can”t afford to waste time and engage in distracting soap operatics by testing men who only think they are the genetic fathers.

To get some sense of the potential variety of “non-paternity events,” note that three of the seven most recent presidents went by different surnames at some point in their lives.

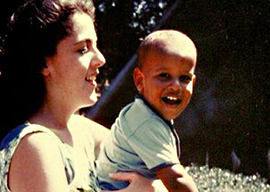

Barack Obama used to be Barry Soetoro. Bill Clinton was originally William Blythe III after his (presumed) father, who died in a car crash in 1946.

And Gerald Ford, that embodiment of heartland stability, was Leslie King Jr. as an infant. His mother quickly divorced the wealthy but erratic King and married Gerald Ford Sr. before her son turned three. The future president was not aware of who his genetic father was until he was 17.

As an instance of outsider misattribution, note that Indonesians tended to make up a complicated story to explain how little Barry Soetoro could look African but be Indonesian. One might expect that his African looks would strike them as exotic, but Indonesians often assumed his skin tone and woolly hair meant he was part Papuan. David Maraniss’s exhaustive biography of the president, Barack Obama: The Story, reports:

When [his mother] Ann accompanied him to school the first day, [his teacher] Ms. Pareira was confused. He looked like he was from Ambon, one of the thousands of islands comprising Indonesia. It was nearly 1,500 miles east of Jakarta, and the people there were known for having darker skin.

Maraniss even finds a brother of Lolo Soetoro who agrees that Barry looked like some Soetoros. In the only funny moment in a tedious tome, Mr. Soetoro happily reminisces that his siblings seemed to come out of the womb looking, amazingly enough, like the men of whatever island the family happened to be living upon. (No disturbing surmises about his mother occur to him.)

Maraniss’s research suggests a bizarre but intriguing hypothetical question. If Barry had been raised to believe he was Indonesian-American, would he still have become president? Or would Obama’s fabulous career have never gone anywhere without his laboriously acquired claim to an African-American identity?