September 21, 2017

Alas, the only place Eggshells was ever seen was on a few college campuses, where, Hooper lamented, “as soon as the lights went down, the Bic lighters would all go on.” Billed on the poster as “An American Freak Illumination: A Time and Spaced Film Fantasy,” the movie failed to return a single dime.

It was the low point of Hooper’s life—yet it led to the high point. The most memorable actor in the film—partly because he appears in a wild full-frontal-nude sequence, setting fire to his car and his clothes before frolicking through a meadow—was none other than Kim Henkel, working under the pseudonym “Boris Schnurr.” It turns out that the famous horror partnership germinated because Henkel happened to be living in the communal house Hooper chose for his location.

“After that lamebrain psychedelic hippie thing we made,” Henkel recalled, “Tobe and I became casual friends. He wanted me to develop a script with him. But he moves at an exasperating pace. We were working on a modern version of ‘Hansel and Gretel’ for almost a year. The bad guys in the story were ‘electronic fields.’ That was his idea. I told him we needed something more sinister than ‘electronic fields.’ That hadn’t worked in Eggshells. We had no budget, we had no cast, and the last picture had not been successful. What do you do? Horror films is about it.”

The way Hooper recalled it later, the inspiration for Chain Saw occurred at a Montgomery Ward department store during the frenzied Christmas shopping rush in December of 1972. “There were these big Christmas crowds, I was frustrated, and I found myself near a display rack of chain saws. I just kind of zoned in on it. I did a rack-focus to the saws, and I thought, ‘I know a way I could get through this crowd really quickly.’ I went home, sat down, all the channels just tuned in, the zeitgeist blew through, and the whole damn story came to me in what seemed like about thirty seconds. The hitchhiker, the older brother at the gas station, the girl escaping twice, the dinner sequence, people out in the country out of gas. I called Kim and said, ‘I’ve got it.’”

“I got this call from Tobe,” Henkel recalled in a less dramatic version, “and he said he’d been thinking about the story and wanted to get together. I went over to his house and we talked through the story, and then I started going over there every evening and figuring out the structure, and then I started writing in his kitchen. I would write four or five pages and then take them to him and we’d go over them. Mainly we were working out a feel. We wrote the first draft in six weeks, from February to the spring, and we were shooting the film by that summer.”

They kept the original idea of an updated “Hansel and Gretel” story—“only instead of being lured to a gingerbread cottage with gumdrops,” said Henkel with understatement, “it was a little more sinister.” To create the modern version of a witch who bakes children in pies, they studied the then-scant literature on real-life cannibals and serial killers.

Hooper had relatives from Wisconsin who had told him gruesome stories as a child that he later discovered were mostly truthful—the legends surrounding Edward Gein, a handyman in the small town of Plainfield who liked to dig up fresh graves, cut the skin off corpses, wear it on various parts of his body, and dance in the moonlight. When the authorities finally caught him in 1957, he confessed to two murders in his quest for fresh body parts, and in his house they found skulls on the bedposts, a human heart in a saucepan, and a woman in his barn dressed like a deer. All the members of his family had died, and he was suspected of never burying his mother and possibly killing his brother. He showed clear signs of being a transsexual—he always dressed in female body parts, especially breasts, vaginas, nipples, and the faces of women—and would spend the rest of his life in the Central State Hospital for the Criminally Insane, where he was known for his rock jewelry. He died in 1984, but not before he had inspired characters in Psycho, Deranged, Maniac, and, most notably, Silence of the Lambs. Says Ron Bozman, who production-managed Chain Saw and produced Lambs, “I guess I’m the only guy who worked on both of the most famous Ed Gein movies. But Tobe’s version was by far the wilder ride.”

The character of Leatherface was not strictly based on Gein, though. “I definitely studied Gein,” said Henkel, “but I also noticed a murder case in Houston at the time, a serial murderer named Elmer Wayne Henley. He was a young man who recruited victims for an older homosexual man. I saw some news report where Elmer Wayne was identifying bodies and their locations, and he was this skinny little ole 17-year-old, and he kind of puffed out his chest and said, ‘I did these crimes and I’m gonna stand up and take it like a man.’ Well, that struck me as interesting, that he had this conventional morality at that point. He wanted it known that, now that he was caught, he would do the right thing. So this kind of moral schizophrenia is something I tried to build into the characters. Like when the old man is so upset that the door was chopped down. ‘Look what your brother did to the door! Don’t you have any pride in your home?’”

Once they had the script, called Head Cheese, Hooper and Henkel showed it to Warren Skaaren, the nerdy, well-scrubbed Minnesotan who had become the first head of the Texas Film Commission. Skaaren in turn took it to Bill Parsley, the flamboyant lobbyist for Texas Tech University, and Parsley eventually agreed to raise a $60,000 operating budget in exchange for 50 percent of the picture. Parsley’s lawyer threw in $10,000, Henkel’s sister a thousand, and one of the lawyer’s criminal clients, a reputed drug dealer from South Texas, added $10,000 of his own to the kitty. Skaaren made his most lasting contribution to the film just one week before principal photography commenced that summer. He suggested that Hooper and Henkel throw out both of their working titles—Head Cheese and Leatherface—and call it The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

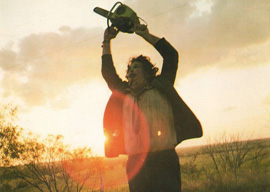

Chain Saw was the first baby-boomer horror film, in which sheltered but idealistic suburban children, distrustful of anyone over 30, are terrorized by the deformed adult world that dwells on the grungy side of the railroad tracks. There had been other films that treat rural America as a place of seething, barely-contained violence—notably Deliverance—but never one in which the distinction is so clearly made between an old America, of twisted deranged adults, and the new America, of honest right-thinking children. Hooper and Henkel had finally made their counterculture film after all.

Legend has it that, on a certain evening in October of 1974, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was sneak-previewed at a theater in San Francisco, where half the audience got sick and others pelted the screen, yelled obscenities, and demanded their money back. Fistfights broke out in the lobby, and the film became famous. The reality is probably less colorful. The most credible version is that several San Francisco politicians, including City Council members, had gone to a special screening of the movie The Taking of Pelham 1-2-3, and it was a coincidence that Chain Saw was being sneaked as a second feature. The politicians were outraged, and therefore the press heard about it. Knowing what we now know about Bryanston Pictures—the Mafia-owned company that ended up with distribution rights—very few things involving Chain Saw were coincidental. There’s a good possibility that the whole thing was staged to create a controversy. At any rate, a myth was born that night—that there was not only a horrific new movie, but a new kind of movie, the most violent film ever made, a docudrama so nauseatingly and relentlessly gory that it tested the very limits of what the First Amendment allows. (It’s no coincidence that Bryanston was simultaneously distributing Deep Throat, whose release in 1972 started free-speech debates and triggered prosecutions that would continue throughout the ’70s.)

The movie was an overnight hit. Bryanston had done a masterful job of marketing, beginning with the classic poster, which today sells for $500 and up. “The story is true,” it announced with classic showmanship. “Now the movie that’s just as real.” Johnny Carson made disapproving jokes about the movie. Rex Reed called it “the scariest movie I’ve ever seen, the Jaws of the midnight movie.” The Los Angeles Times called it “despicable…ugly and obscene…a degrading, senseless misuse of film and time.” But, of course, the bad reviews helped just as much as the rare good one. By the time it reached New York, it had become just as notorious as Deep Throat, if somewhat less popular with the East Coast intellectuals who had so vigorously defended Harry Reems and Linda Lovelace. Especially offended by the film was Stephen Koch, a friend of Andy Warhol and author of a book on Warhol’s films. He called Chain Saw “a vile little piece of sick crap” and part of a growing “hard-core pornography of murder” that should best be compared to snuff films.

The problem with the New York critical debate was that every commentator made some kind of basic factual error about what is actually in the film. The idea that the story could take place only in Texas informed a lot of the more hysterical articles, ignoring the fact that the principal source material was from medieval German folklore and Wisconsin court archives. If you read enough of the reviews, in fact, you start to think that the scariest word in the title was neither “chainsaw” nor “massacre,” but “Texas”!

The fame of the movie—or its ignominy, depending on how you looked at it—would follow Hooper the rest of his life. For his next project, Kurdish film distributors in Southern California hired Hooper to do a Chain Saw-type horror story from an existing script (rewritten by Henkel) about an insane motel manager who feeds his guests to the alligators that live in the swamp out back. They shot it in three weeks at Raleigh Studios in Hollywood, but even with Marilyn Burns as the lead, lightning did not strike twice. Mel Ferrer, Stuart Whitman, and Robert Englund—who would later become “Freddy Krueger”—rounded out the cast of Eaten Alive, also known as Legend of the Bayou, also known as Brutes and Savages, also known as Death Trap, also known as Horror Hotel, also known as Horror Hotel Massacre, also known as Murder on the Bayou, also known as Starlight Slaughter, which failed to make money regardless of how many times it was retitled and rereleased.

And that was the last time the Hooper/Henkel team would work together. They had scored an office on the backlot at Universal Studios, but they were so naive that they didn’t realize that a three-picture “first look” deal was the equivalent of being given a short-term lease in a trailer park. Hooper had always been fascinated by Los Angeles and plunged into the fray, landing a plum TV job directing the Stephen King novel Salem’s Lot as a CBS miniseries, but Henkel eventually tired of Hollywood and returned to Texas, where he wrote one of the best indie films of the ’70s, Eagle Pennell’s Last Night at the Alamo.

Then Hooper was hired to direct what should have been his ticket to lasting fame and fortune—Poltergeist.

Poltergeist was his first big-budget picture and an unqualified commercial success. He had pitched into the project joyfully with his new friend and executive producer Steven Spielberg, and they jointly worked out the casting and the general shooting schedule. Like kids at play, they called each other several times a day, and when production began, Spielberg wanted to be there. On a particular day, when a Los Angeles Times reporter was visiting the set, Spielberg happened to be shooting second-unit work in front of the house while Hooper was in the backyard getting a scene in which a tree comes to life in the little girl’s dreams.

The following week an article appeared in the Times implying that Hooper was not really directing Poltergeist at all and that Spielberg was not just the executive producer but was ghost-directing. The clear implication was that Hooper was not up to the job. Hooper was naturally disturbed by the article and wrote a letter to the reporter trying to clear things up. Spielberg became irate when he found out that Hooper had written the letter. Spielberg had investors and backers who wanted him working on another project at the time; he was concerned that support for that project would dry up if he was caught “goofing off” on Poltergeist. Spielberg told Hooper to just keep his mouth shut, and relations between the two men became strained. (They later patched things up, and Hooper would go on to work on several other Spielberg projects, including The Others and the pilot for Taken.)

But the damage had been done. When the movie was released, review after review took note of the rumor that Hooper hadn’t really directed it. Spielberg finally took out full-page ads in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter, giving Hooper full credit for the film and discounting the rumors, but no one really believed it. As late as this year—35 years later!—an assistant cameraman was giving interviews to a blogger saying he witnessed Spielberg ghost-directing, and the libel was passed along to the public even though the cameraman had no access to the daily directorial meetings.

Twice successful, twice cursed—Hooper seemed to be the only director in history who couldn’t get work even after two movies that earned more than $100 million each, movies that would both be acclaimed as classics. Time and again he was asked to “prove himself,” even as Poltergeist took the suburban multiplexes by storm and Chain Saw continued to play drive-ins, overseas territories, and midnight-movie houses (often on a double bill with David Lynch’s Eraserhead). After a five-year censorship fight in France, Chain Saw opened on the Champs-Élysées in 1982 and had grosses higher than Superman. For a 1983 rerelease by New Line Cinema, the gross was $6 million, an unheard-of figure for a nine-year-old film that had already been released on video. Chain Saw would end up being seen in more than 90 countries, sometimes dubbed, sometimes subtitled, sometimes marketed in an almost unrecognizable way. (In Italy, it was called Non Aprite Quella Porta, or “Don’t Open That Door.”) A remastered print would be rereleased for the film’s 40th anniversary in 2014 and sell out special screenings all across the country. Its appeal, for better or worse, was universal.

No matter. After Poltergeist Hooper was forced back into the independent-film world. The only reason he agreed to do the first sequel to Chain Saw is that the Israeli-owned Cannon Films promised to finance two other pet projects of his. He got a $20 million budget for the superb Lifeforce, which had mixed reviews but poor box office, and he followed that with a remake of the classic Invaders From Mars, which got a good critical reception but underperformed. Then, to satisfy his obligation to Cannon, he reluctantly churned out Chainsaw 2 with a $4.5 million budget.

The film made money—and over the past 15 years it has acquired status as a cult favorite—but it didn’t have the power of the original, partly because Hooper chose not to use Henkel. Instead he asked Kit Carson, of Paris, Texas fame, to write it. Maybe it was ahead of its time, but the comedic treatment of the Chain Saw family—Carson envisioned it as “the horror version of The Breakfast Club”—just didn’t fly with serious fans of the original, and everyone who worked on part 2 thought Hooper seemed detached and unchallenged.

There were other attempts to revive the magic. In 1988 New Line decided to make yet another sequel. It’s obviously set in California, with none of the original cast, and with a director who didn’t appear to know what universe he dwelt in. Then, twenty years after the original film was released, Bob Kuhn, one of the original investors, convinced Henkel that he should write and direct yet one more sequel, set the day after the original, ignoring the story lines of the two films released by Cannon and New Line. Return of the Texas Chainsaw Massacre was budgeted first at $500,000, then $800,000, and ended up costing $1.5 million—again raised from Austin investors. The movie should have been a hit. It was certainly the best-written, best-acted, and best-directed of all the sequels, and it had the star power of Matthew McConaughey and Renée Zellweger, who were unknown Austin actors when Henkel cast them but had become “names” before the movie was released. (Top billing on the film went to Tyler Cone and Robert Jacks.) But the release was sabotaged by Hollywood agents trying to “protect” their clients and a management at Columbia/TriStar that was embarrassed by an inherited project they wanted to quickly play off on video.

By then Hooper was running as fast as he could to get away from the “chain saw” typecasting, but he always struggled, taking television work (The Equalizer, Freddy’s Nightmares, Tales From the Crypt, movies-of-the-week) and making the occasional low-budget feature, like Funhouse or Spontaneous Combustion, financed by people hoping to repeat the Chain Saw success story. By the ’90s he was sufficiently well-known to have his name above the title in the anthology film Tobe Hooper’s Night Terrors, and he was sufficiently respected by ABC golden boy Jeff Sagansky to be entrusted with the pilot for Sagansky’s pet project of 1996, Dark Skies. He continued to work in both television and film until recently, finishing out his theatrical film career with a remake of Toolbox Murders (2004) and the disappointing Mortuary (2005).

I’m not really counting his final project, in 2013, which was financed and produced in one of the few places in the world where The Texas Chain Saw Massacre had never been released—the United Arab Emirates. Like almost everything else in Hooper’s life, the production of Djinn was plagued by local politics, censorship, a delayed release caused by government concerns, and so many hands in the pie that we have no idea what he intended. It’s not a great film, but it’s the first Middle Eastern horror movie—filmed in both English and Arabic—and I can’t imagine a part of the world that needs horror more. No doubt someday the Emirati will realize who was in their presence. Someday they will honor him. Someday they will understand what he brought them, and, like everything else he did, others will benefit from his work.

I honor him here and now. He stayed the course. Let us now praise infamous men.