October 07, 2016

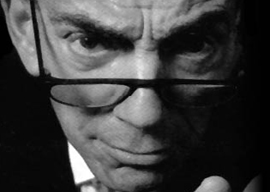

Herschell Gordon Lewis

Source: herschellgordonlewis.com

NEW YORK”My friend Herschell Gordon Lewis, best known as the inventor of the slasher film, died last week in Florida at the officially announced age of 90, but knowing his prickly attitude about his age and the fact that he always looked 50, I wouldn”t be surprised if the real number was ten years higher. Herschell was a tall, elegant, urbane intellectual with a sharp wit who would have been amazed and flattered that The New York Times, of all places, took note of his death and published a long, fairly affectionate obituary.

I was amazed as well”and pissed off. This is the newspaper that ignored his existence during the years when he was making films, years when even a negative review would have helped his box office. Now that he’s safely dead, they”re giving him credit for inspiring John Carpenter and influencing Wes Craven and Quentin Tarantino.

Herschell had about as much influence on Quentin Tarantino as the inventor of the three-pronged pitchfork had on Friday the 13th. If Wes Craven even watched, much less appreciated, any of Herschell’s films, it was most likely to use them as a horrible warning not to oversaturate the screen with phosphorescent stage blood. John Carpenter is a superb craftsman”Herschell was a businessman who had trouble understanding cinematic principles unaltered since the time of D.W. Griffith. I have to wonder if this obituary is some kind of weird Times cleansing ritual, awkwardly dealing with a pop culture hero in some way that won”t offend the ballet critic. At any rate, it’s too bad Herschell isn”t here to witness the Gray Lady’s discomfiture, since he was all about making people squirm.

I only knew Herschell for the last thirty years of his life, beginning on the day I made a sojourn to Plantation, Fla., to tell him that 90 percent of his films had been rescued from warehouses and were about to be released in a series hosted by myself and distributed by the London company Strand Video. Herschell answered the door at his stylish condo, impeccably dressed as usual in his trademark blazer and tie, and motioned me into the kitchen, away from wife Margo’s ability to hear us.

“She’s not crazy about this aspect of my life,” Herschell whispered, and then, “You”re going to release these films? How? And, more to the point, why?”

Like many exploitation filmmakers of his generation, Herschell was under the impression that films were disposable artifacts, of no value once they had been “played off” around the country. He hadn”t saved any of his own prints, and had long since sold the ancillary rights. Herschell was primarily a marketer, not a filmmaker, and his genius was the ad campaign, not the film itself. Every one of Herschell’s films was something of a bait and switch, never quite delivering what the lurid posters promised.

His greatest achievement, a story well-known among producers, was the release of Blood Feast on July 19, 1963, at the Bellevue Drive-In in Peoria, Ill.

Stanford Kohlberg, a P.T. Barnum type who tried everything from pony rides to hot-air balloons to fireworks shows to popularize his chain of drive-in theaters, had put up the money for the film”$24,500, to be painfully precise. It didn”t have much going for it in the way of acting, plot, or production values, but it did have one new element: blood. Not just a little squib on the shirt when someone died, but gouts of blood, gallons of it, spurting and gurgling out of bodies in extreme close-up as a maniac Egyptian caterer named Fuad Ramses slaughtered virginal girls and prepared a cannibalistic feast from their body parts. As the advertising poster put it:

NOTHING SO APPALLING IN THE ANNALS OF HORROR! You”ll Recoil and Shudder as You Witness the Slaughter and Mutilation of Nubile Young Girls”in a Weird and Horrendous Ancient Rite! AN ADMONITION: If You are the Parent or Guardian of an impressionable adolescent DO NOT BRING HIM or PERMIT HIM TO SEE THIS MOTION PICTURE! Introducing CONNIE MASON: YOU READ ABOUT HER IN PLAYBOY. MORE GRISLY THAN EVER IN BLOOD COLOR!

On the day of the premiere, Herschell and his partner Dave Friedman became so curious about what they had wrought that they made a last-second decision to drive down from their Chicago office. They hopped into Herschell’s Chrysler Imperial and stopped to pick up their wives (who despised the film), and when they got to Plank Road, about a mile from the theater, ran into a traffic jam. At first they thought there was an accident ahead, then it slowly dawned on them: All the cars were lined up to see Blood Feast. A legend was born.

What’s interesting about the story is that the movie was obviously a success before anyone had actually seen it. The crowds thronged the theater on the basis of the ad campaign alone. It did continue to make money”$17,000 for the one week it played in Peoria, followed by bookings over the next fifteen years that earned an estimated $7 million. That’s a terrific profit”286 times return on investment”but it’s no blockbuster even by the standards of the “60s.

Blood Feast was impressive primarily for its sheer longevity, moving around the country one week at a time, so that as late as 1980 it was still turning up in drive-ins, sometimes on a double bill with Tom Loughlin’s Born Losers. Unlike most cult movies, though, you”re not likely to find many film buffs who saw it during its first release. It wasn”t that kind of movie. In the cities, Blood Feast played grindhouses as an occasional respite from their steady diet of softcore porn. In less populous areas it played drive-ins, often as a late second or third feature when presumably the “family audience” had already gone home. In both cases it had an almost entirely male clientele, bored and lonely seekers of cheap thrills. Not the kind of guys who write cult-film memoirs.

Then, around 1983, twenty years after its debut, the reputation of the film underwent a miraculous sea change that would make it all but immortal in underground-film circles. And it’s no accident that it happened at the pinnacle of the punk-rock movement. Quite a few metal bands recorded songs in tribute to famous scenes in Herschell’s movies. The group 10,000 Maniacs was intended as a tribute to Herschell’s follow-up film, 2,000 Maniacs, but the band got the name wrong. Blood Feast became hip with a young generation that was highly educated, media-saturated, and rebelling against everything in the culture that was plain vanilla or beloved by the masses. As low culture became high camp, Blood Feast was loved because it was despised.

By the time he became famous, though, Herschell was long retired from filmmaking and had settled comfortably in South Florida, where he made a small fortune as one of the world’s leading authorities on direct-mail marketing, better known as “junk mail.” He wrote books on the subject, conducted seminars around the world, and hired himself out at $10,000 per letter if you wanted him to write your direct-mail piece. (The three principles of effective junk mail, he once told me, were fear, guilt, and greed”so his chosen craft was not that different from an exploitation-film campaign.)

When I first met Herschell during that memorable encounter in Plantation, he spoke fondly of his old films, but seemed not quite aware that they were famous. Like most people encountering him for the first time, I was struck by his professorial manner. He spoke the perfect King’s English and had, in fact, a Masters degree in journalism and a Ph.D. in psychology”he could have legitimately billed himself as Dr. Lewis. In the “50s he had taught English and humanities at Mississippi State University before he decided he”d rather make money. He became an itinerant journalist, taking jobs at radio stations in Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, before becoming a producer at WKY-TV in Oklahoma City and then a copywriter for a Chicago advertising agency. He was just ready to go out on his own when he met Dave Friedman, a carnie from Alabama, and together they formed Mid-Continent Films.

The two men started in 1960 with a movie called The Prime Time, starring “seven of the ugliest girls ever to appear on film,” according to Herschell, even though one of them was Karen Black in her movie debut. They followed that up with an “artists and models” programmer called Living Venus, starring Harvey Korman, then a silly burlesque film called The Adventures of Lucky Pierre that earned $175,000 on an investment of $7,500. They hit their stride when they discovered “nudie-cuties,” the almost unbearably boring genre that flourished from 1960 to 1963. A series of court decisions allowed nudity on the screen for the first time, but only if the film took place entirely within a nudist camp. This led Herschell to Florida, where he made Daughter of the Sun, Nature’s Playmates, and Boin-n-g! (yes, the title means what you think it means), but by 1962 the nudist-camp fad was starting to fade and Friedman and Lewis went in search of new genres. That fall they shot Scum of the Earth, about a gang of pornographers who lure young college girls into posing for dirty pictures, but their big break came when Friedman hooked up with the owner of the top burlesque theater in Cincinnati, Eli Jackson.

Jackson wanted to finance a nudie film starring his wife, the stripper Virginia “Ding Dong” Bell (measurements 48-24-36), who was so well-known nationally that she commanded a queenly $1,500 a week. Herschell and his partner made a quick deal to shoot the film as hired guns”the finished product, lost to posterity, was called Bell, Bare and Beautiful“but it was really just an excuse to put together a cast and crew with someone else’s money so they could use the extra time to make Blood Feast at the Suez Motel in Miami Beach.

The two key performers were Connie Mason, the Playboy Playmate who was so lifeless and unprepared that she drove Herschell insane (“She never knew a single line, not one, ever”), and Mal Arnold as the maniac Egyptian. Arnold was a local actor who had seemed okay at his interview”he had been an extra in one of the nudie-cuties called Goldilocks and the Three Bares“but when the camera rolled he insisted on using the world’s worst Bela Lugosi accent, bugging out his Groucho Marx eyebrows, and exaggerating a hokey limp. A great deal of the movie’s cult value is created by the yin-and-yang effect of the beautiful Connie Mason’s deadpan nonacting with the slimy-haired Mal Arnold’s delirious overacting. In one scene Mason is obviously reading her lines from a table lamp, and in another Arnold seems to be in a trance as he wields a barbed whip on a female victim clad in tattered panties, chained to a blood-smeared wall. “Stop your sniveling!” he barks at her.

Fortunately the facade of the Suez Motel featured a garishly painted plastic replica of the Sphinx, which, shot from below at dusk, could almost be made to look like the real thing. Creating Fuad Ramses” shrine to the goddess Ishtar (“I am your slave, my lady of the dark moon!”) would prove more daunting. A department-store mannequin was painted yellow and dressed in vaguely Arabian attire, but it looked neither menacing nor interesting. Friedman solved the problem by driving to the Miami Serpentarium and purchasing a seven-foot-long Colombian boa constrictor for thirty bucks. They draped it over the mannequin”it still doesn”t look that creepy”and used the snake in a couple of other scenes for no particular reason save ambience.