April 21, 2016

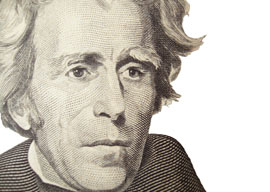

Andrew Jackson

Source: Bigstock

Instead of wishing he”d shot Henry Clay, I bet Andrew Jackson is now wishing he could plug Treasury Secretary Jack Lew.

This week, Secretary Lew is expected to announce that Andrew Jackson’s visage will be wiped from the $20 bill in favor of a woman’s. Thanks to the wildly successful rap musical Hamilton, based on the life of founder Alexander Hamilton, the architect of the nation’s financial system will keep his place on the ten-spot. That leaves Jackson’s neck on the chopping block, as the Obama administration seeks to replace a stale, old white man with a feminine figure representative of our enlightened ideals.

The idea of removing Old Hickory from the federal note is not unpopular. Both Time magazine and The Washington Post have endorsed the purging of the seventh president. The New York Times editorial board wants Jackson gone from the twenty as well. These self-righteous ninnies can”t get over the fact that President Jackson was a slave-owning chauvinist who refused to genuflect before the Washington aristocracy.

The anti-Jackson bromides are not only wrongheaded but ignorant of the president’s impact on American democracy. Jackson was a man of ferocious ambition, of unworldly perseverance, and of seemingly unbreakable grit. He went from orphaned teenager to the highest office in the land, battling enemies far more powerful than himself along the way. His honor-driven frontiersman style is an American motif that has popped up periodically through our history. His effect on how we view government is reason enough to keep his saber-scarred face on our money.

The first time Jackson ran for president he won the popular vote but was denied the office by backdoor finagling between John Quincy Adams and then-Speaker Henry Clay. The corrupt bargain ignited a defiant spark in Jackson, who ran a populist campaign the next go-around, formally ushering in a democratic shift the founders warned against. He derided the political class as corrupt and in the pocket of elite interests (sound familiar?). He gave a voice to the farmers and laborers who had yet to experience political influence in the short history of the republic. The campaign was an incredible success. Jackson won a landslide victory with the backing of poor, newly enfranchised whites.

Jackson’s ascendance to the presidency can be partially attributed to his confronting the country’s powerful banking interests. During his second campaign, he led a Donald Trump-like crusade against the Second Bank of the United States”a kind of precursor to today’s Federal Reserve System”and pledged to end its charter. Jackson won over the public by describing the Bank as the embodiment of unfair privilege. In a letter to James A. Hamilton he wrote, “I was aware that the Bank question would be disapproved by all the sordid, & interested, who prised self interest more than the perpetuity of our liberty, & the blessings of a free republican government,” shortly after winning election. Like the many duels of his youth, Jackson won this fight as well.

The Jacksonian hostile takeover of the Washington apparatus still lives in our national imagination. It’s a rag-to-riches narrative that captures the yearning of the American everyman. Jackson eschewed the backslapping of traditional politics and took his case right to the people. As John Updike’s fictitious Jackson proclaims in Buchanan Dying, “When ye”ve passed through to the other side, Mr. Búchanan, when ye”ve put the fear of the worst behind ye, ye”ll know where the power lies in God’s own country: it lies in the passions of the people…. With the people in yer guts, ye can do no wrong.”

Regrettably, Jackson did do wrong in office. His forced evacuation of the Cherokee from the southeastern United States was odious. As was his owning of slaves on his Hermitage plantation. Depending on your view, Jackson’s planned enforcement of the Tariff of 1833 was either a blow for states” rights or a victory for the Union’s cohesion.