January 14, 2016

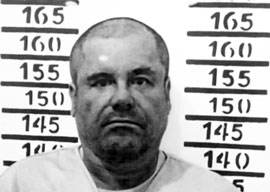

JoaquÃn "El Chapo" Guzmán

In 1974, the legendary Western director Sam Peckinpah made a small masterpiece entitled Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia. El Jefe, a Mexican “boss man” protected by a private army, addresses his gunmen lined up on either side of a banqueting table whose length spells power:

I will pay one million dollars. Bring me the head of Alfredo Garcia!

Forty years later, some things have changed south of the border and some have not. Severed heads remain a frequent phenomenon. Nowadays, Mexican DTOs (drug-trafficking organizations) wield equal, sometimes superior, firepower to their American enemy: the DEA and affiliates. Narcos outnumber Mexican/American drug warriors, each cartel commanding its own large, well-trained armies with near-unlimited funding. The $1″2 billion in aid we allocate to Mexico to fight the Drug War is just a token compared with Mexico’s drug-trafficking trade. Market size: up to $250 billion a year, as Mexico controls roughly 50 percent of the global market”estimated from $320 billion by OAS to $500 million by other agencies.

The recent capture of boss of bosses and three-time fugitive JoaquÃn “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera extends a recurring cycle of escape and recapture resembling a Tom and Jerry cartoon. After escaping from the Altiplano maximum-security prison via oxygenated tunnel, El Chapo was intercepted again on Jan. 9, 2016. On the run, he carried a bounty upon his head of $3.8M from Mexico and $5M from the U.S., totaling $8.8 million. Guzmán himself, in his role as folk hero, placed a bounty on Donald Trump’s head”at $100 million.

Guzmán was previously incarcerated in Puente Grande prison, where he consolidated the Sinaloa cartel’s grip on the business, building a vertically integrated conglomerate that would emerge as market leader in 2015. On the previous occasion he escaped in a laundry cart”more Tom and Jerry. Both escapes clearly mock the ability of law authorities to contain a man who “runs the biggest international drug cartel the world has ever known, exceeding even that of Pablo Escobar,” as Sean Penn wrote in his controversial Rolling Stone interview with the man himself. “He shops and ships by some estimates more than half of all the cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine and marijuana that come into the United States.”

Penn’s interview made for great reading, despite”or because of”the outrage and hand-wringing of politicians and the politically correct. It also made a key point about the War on Drugs that we can not admit to, even at our own expense. Writes the actor/activist:

Are we, the American public, not indeed complicit in what we demonize? We are the consumers, and as such, we are complicit in every murder, and in every corruption of an institution…as a result of our insatiable appetite for illicit narcotics.

Are we saying that what’s systemic in our [prison] culture, and out of our direct hands and view, shares no moral equivalency to…narco assassinations in Juarez? Or, is that a distinction for the passive self-righteous?

Guzmán’s recapture will change absolutely nothing in the drug trade”by his own admission in the Penn interview. Guzmán is but one CEO of crime, although his family members provide an assured hierarchy of succession, commencing with his eldest son, Ivan”according to Penn’s observations. With or without Guzmán, the Sinaloa cartel will survive and dominate. Market forces guarantee its survival. Should the Sinaloans relinquish control of various border points, down the line, business will proceed uninterrupted under command of the next-most powerful cartel.

How did things come to such a pointless, violent impasse?

The explosion in value of the smuggling business took place after the death of Pablo Escobar and the cleansing of Colombia from narco state to U.S.-protected, vibrant, legitimate economy”ending the Colombian suppliers” and neighboring producer nations” control over distribution of their product. Colombia had used Miami and the Caribbean Sea as its primary smuggling route in the 1970s and “80s; the DEA and affiliates successfully closed the maritime trafficking routes in the late “80s. A time when the industry was immature yet growing fast, when the smaller volume of narcotics was more manageable to police. Nowadays, the sheer volumes of drug traffic preclude similar law-enforcement success. How do you stop an avalanche?

With the Caribbean locked down, alternative routes became necessary. Smuggling by land offered many advantages, with Mexico’s vast spaces providing natural shelter and the hyperactive border ensuring invisibility inside a crowd. Mexico’s industrial north contains many cheap-labor factories churning out goods for the U.S. market, and these maquiladoras are situated as close to the border as possible for convenience, given the duty-free, tariff-free nature of their import/export business. A perfect cover for smuggling daily drug shipments in numbers high enough to make the 10 percent routinely intercepted meaningless to the bottom line; a source familiar with the business claims it can easily absorb up to 25 percent in losses of merchandise.

The game plan became, and remains, the basic outnumbering of the enemy (Customs, DEA, FBI). In the late “80s, northern Mexico abruptly became a highly valued territory, with its central, U.S.-bordering state of Chihuahua (Mexico’s largest) making for a natural corridor to the USA. A corridor so large it gained a new name: “la Plaza.”

The first high-profile Mexican drug lord, named Pablo Acosta, gained control of the Plaza by the mid-“80s. In so doing, he commoditized Mexico’s geography according to the value of its smuggling routes”and he changed the nature of the business by creating a franchise system. Monopolized by Acosta, traffickers paid him a tax whenever they crossed the Plaza. The system worked nicely, keeping potential rivals happy enough not to desire Acosta’s elimination. Violence was minimal.

An industry was born. The control of all the territories inside Mexico offering smuggling routes has since been exploited by respective owners or overruling cartels. The significance of Mexico’s cartel-divided landscape to traffickers transformed turf battles into full-on factional wars. La violencia became widespread by the mid-2000s; then it spiraled way out of control. It wasn”t helped by former president Calderón declaring a public war on the cartels, costing his people 100,000 fatalities in just five years.

Why is the competition here so fierce, it made Juarez the most dangerous place on earth in 2009″10, more so than Iraq or Afghanistan?

It’s the money, of course. And a rivalry between regions inside Mexico beyond the understanding of a gringo. A cartel’s integrity is based on qualities, perversely, that we may have lost, at times, in our own pursuit of prosperity”see: the financial crisis of 2008. Cartel identity depends on a blind loyalty and rigid hierarchy we might consider provincial, even feudal.

The cartels” staying power lies in the obedience of the ranks to their command. The Sinaloa cartel’s model of organizational behavior is worthy of a Harvard case study. Its corporate structure is”aside from financial motivation”built on trust and respect (if you wish to stay alive), which may be intimidating but works like Swiss clockwork. The business is indestructible. No law-enforcement agency”if we admit the truth”can compete with the dynamics of this gigantic and extremely well-organized (black) market. No denying it: Cocaine”the 11th-scarcest commodity in the world”is a great investment, from the kilo level going upward. It’s a dream product. It’s also illegal, which conveniently keeps the marketplace private and easily controlled, somewhat like “dark pools” in our capital markets.