December 14, 2016

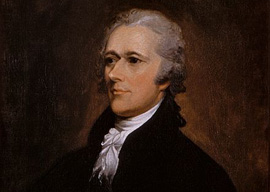

Alexander Hamilton by John Trumbull

Donald Trump’s era of influence may turn out to be a flash in the pan like that of previous celebrity politicians Jesse Ventura and Arnold Schwarzenegger. But he may also be building a political system as enduring as Ronald Reagan’s.

A clever aspect of Trump’s platform that hasn”t been much analyzed is that by merging the issues of immigration and trade into the super-issue of borders, he may have a way to reliably win both votes and political donations.

By defeating Hillary despite spending only half as much, Trump demonstrated that much of traditional campaign expenditure is waste. And yet a party still needs some special interests to write big checks. Trump pulled off a sensational tour de force by defeating the overwhelming majority of America’s establishment, but no party can rely on individual heroism as a long-term strategy.

A Trump reelection campaign will need to appeal to at least some special interests. The history of the GOP from 1860 onward suggests that trade policy can be a major stimulus for campaign funding.

The weakness of immigration restriction as an issue has not been a lack of popularity with voters, but a lack of pocketbook appeal to major donors. Countless special interests can benefit from lax immigration laws and laxer enforcement, so politicians pushing open borders receive huge payoffs from the wealthy.

Prudent immigration policy, in contrast, is good for ourselves and our posterity, but there’s no way to get rich off it. By itself, immigration restriction is just too clean of an issue. That appeals to eccentric idealists like me, but we generally don”t have much money.

Having been in the immigration policy business for the entire 21st century, let me assure you that it’s not an easy way to make a living. I”ve never stumbled upon any special interest that would benefit financially from more prudent immigration policies. The only strategy I”ve thought of is appealing to the civic-mindedness of rich guys.

To get a sense of this, notice that in screeds by the opulently funded Southern Poverty Law Center about the menace posed by immigration patriots, their most virulent hatred is reserved for Dr. John Tanton for his role in key fund-raising.

Who is this nefarious Dr. Tanton who so outrages the SPLC (with its current endowment of $303 million)? Is he some Bruce Wayne-like billionaire glowering over a great city from his personal skyscraper?

No, Dr. Tanton is an ophthalmologist in Petoskey, Michigan, up near Mackinac.

How many billionaires are on the side of immigration prudence? In 2014, I went through the Forbes 400 and noticed two members of the bottom 100 (not that that’s a bad place to be) who donated to restrictionist causes. (I won”t mention their names because of all the hate and violence directed toward patriots in 2016.) And I theorized back then that Ross Perot and Donald Trump weren”t enthusiasts for more immigration.

In contrast, billionaires tend to know on which side their bread is buttered. Plutocrats in the top three dozen richest people in the country in 2014 who were publicly donating money to boost immigration numbers included Bill Gates, the Koch brothers, Michael Bloomberg, Sheldon Adelson, George Soros, Mark Zuckerberg, Rupert Murdoch, and the widow Jobs.

That’s a rather daunting list of opponents. Staring at their names just now, I realize I must have been nuts to devote my career to opposing the whims of people like them. What was I thinking?

While immigration restraint on its own will never appeal to any but the most idealistic billionaires, lumping immigration and trade together as borders has potential to get the attention of more self-interested plutocrats.

For example, one of the main monetary supporters of National Review for decades was textile-factory baron Roger Milliken. The main thing he wanted in return was support for a protective tariff on textiles because he didn”t want to shut his South Carolina mills. Milliken’s contributions did much for several decades to restrain NR‘s drift toward trade libertarianism.

With average tariffs as of 2010 down to 1.3 percent, the returns from further cutting of tariffs are marginal. Indeed, most trade negotiations in recent decades have been about the sly non-tariff barriers that other countries use to keep out imports.

For example, all through the 1970s the Japanese government promised that real soon now the Japanese would be buying lots of American cars. In reality, while Japanese government safety inspections and other shenanigans played a role in stifling American exports, the main reason was because Japanese people wanted to build and buy Japanese cars.

Eventually, Ronald Reagan grew frustrated enough that he imposed a quota on Japanese auto imports. In turn, the Japanese car companies built factories in America. This struck me as reasonably successful, but it has largely been forgotten during the triumphalist phase of globalist ideology.

I was an economics major, and the surest sign that you”ve been to college in America is the ability to explain why Ricardo’s law of comparative advantage proves that free trade must be optimal.

Thus, I once got denounced by a couple of National Review writers for joking that the surest proof of the infallibility of free-trade theory was that hardheaded statesmen such as Alexander Hamilton, Abraham Lincoln, and Otto von Bismarck all favored it.